The Nonprofit Quarterly and the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) are pleased to present the fourth in a series of articles based on insights and lessons from Philamplify, NCRP’s new initiative that combines expert assessments with stakeholder feedback to help improve the effectiveness and impact of the country’s foundations.

A recent Washington Post series on black homeownership contained startling national statistics: The net worth of the typical African American family declined by one-third between 2010 and 2013, significantly more than white or Hispanic families in the same period. It also noted that the “top half of African American families” has been left with less than half the wealth they possessed in 2007, compared to the 14 percent decline experienced by white families. Ultimately, the series reported, “the typical African American family was left with about eight cents for every dollar of wealth held by whites.”

In the midst of frequent reports like this one and an increasingly vocal movement for racial justice, it’s an opportune time to reflect on how we define progress toward racial equity and, in light of those various definitions, assess foundation responses to systemic inequities. NCRP’s Philamplify initiative has been a great tool for learning more about philanthropic approaches to equity issues. We are discovering how important it is for funders and their grantees, and researchers and those providing feedback, to have a common understandings of terms like “racial equity.” Lack of a common frame can make it difficult for foundations to assess their effectiveness in this area.

One of our assessment criteria examines the extent to which a foundation’s grantmaking and operational strategies demonstrate its commitment to underserved communities by addressing sources of inequity. We defined inequity as “disparate outcomes, impacts, access, treatment, or opportunity for underserved communities based on race, ethnicity, income, gender, sexual orientation, disability, national origin, or other disadvantaged populations.” To measure this criterion, we review a foundation’s mission, goals, strategies, grant guidelines, and recent grants; interviews with staff (if the foundation cooperates), grantees, peers and other knowledgeable stakeholders; and grantee survey questions. We look at strategy as well as impact: Does the foundation say it’s trying to achieve greater equity, and is there tangible evidence that it’s doing so?

Results from the first round of assessments, released in May 2014, demonstrate why we need to seek out multiple sources of information to gain an understanding of a foundation’s approach to equity issues. The contrasts between each foundation’s own language around equity, grantees’ perceptions, and what other stakeholders say are instructive.

Since foundations may not always frame their work using the words “equity” or “justice,” what are other indications that they seek to address these issues? Because the roots of inequity are systemic, and those suffering inequities are populations that are traditionally marginalized (for their race, income, ethnicity, gender, LGBT status, disability, incarceration record, etc.), we look for evidence that a foundation seeks fundamental change that benefits specific marginalized communities. If a foundation is funding direct services for marginalized groups but is not also trying to change systems, can it be said to be advancing equity? I would argue that it is not.

Services may mitigate inequity, but alone they do not address its causes. In their racial justice grantmaking assessment, the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE) and Race Forward (formerly Applied Research Center) asserts: “Racial justice work specifically targets institutional and structural racism through a continuum of activities that can include research, education, organizing, advocacy and movement building.” Conversely, if a foundation seeks systemic reforms without targeting specific populations to benefit from those reforms, is it advancing equity? Not necessarily, because reforming systems without attending to which populations are experiencing disparate outcomes and why may not solve the inequity.

To help us understand intent and strategy, we reviewed materials from the first five foundations we “Philamplified.” Some foundations were very explicit about equity or showed a commitment to systems change benefiting specific disenfranchised communities. As Table A shows, Lumina Foundation for Education and The California Endowment (TCE) each used explicit equity language in framing the problems of unequal higher education and health outcomes, respectively. They each identified specific populations intended to benefit from closing the equity gap, and both were explicit about using strategies that would change the policies, structures and systems perpetuating these inequities. The William Penn Foundation (WPF) also addressed equity issues, specifically in K-12 education, and identified public funding formulas as one systemic solution. WPF did not go as far as the other two in specifying race as a dimension of inequity, preferring to keep the focus on income (although the public school population in Philadelphia is over half African American and 85 percent non-white). And it did not explicitly address equity in its other program areas, watershed protection and arts and culture.

Table A: Review of 2013-14 Foundation Materials (Mission Statement, Strategic Plan, Grant Guidelines, etc.)

|

Foundation |

References to (In)Equity |

References to Systems Change |

References to Specific Underserved or Marginalized Populations |

|

Daniels Fund |

N/A |

K-12 Education Reform: seeks to fund “Significant reforms that challenge barriers to quality.” |

Programs areas serve: Youth and Adults with Substance Use, People with Disabilities, Homeless & Disadvantaged. |

|

Lumina Foundation for Education |

Strategic Plan: “equity imperative” to close gaps in higher education attainment by race/ethnicity. |

Closing gap “will require significant shifts in the priorities and structure of higher education.” Strategy is to “promote action by and through many individuals, organizations, institutions, and governments” |

Targeted populations include African Americans, Latinos, Immigrants, Veterans. |

|

Robert W. Woodruff Foundation |

N/A |

N/A Sign up for our free newslettersSubscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox. By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners. |

Targeted populations for Human Services are: Vulnerable Populations, including the Elderly and Disabled |

|

The California Endowment |

“People in our communities are needlessly suffering because, as a society, we deny them access to essential resources, sending them the message that they don’t matter; they don’t belong. The odds stacked against these populations are the legacy of our nation’s systematic devaluation and discrimination against certain people based on race, immigration status, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, and so on. And just because discrimination for most of these populations is now illegal, we cannot deny that the legacy, and sometimes even the practices, persists.” |

Building Healthy Communities strategy: “is about changing rules at the local and state levels so that everyone is valued and has access to the resources and opportunities essential for health…” |

“Where we live, our race, and our income each play a big part in how well and how long we live.” “This is why race and income come together in place, and this is why TCE’s Building Healthy Communities strategy includes a deep investment in place.” |

|

William Penn Foundation |

Closing the Achievement Gap: priority given to grantees with a “clear commitment to equitable access” to education. Funding for “Targeted, state-level advocacy to secure adequate and equitable funding for Philadelphia schools.” |

Watershed Protection: “Advance policies and practices that accelerate or expand public and private watershed protection.” |

Closing the Achievement Gap & Arts Education each target “low-income children and students” for benefit. Great Public Spaces objective: “Increase access to green space in an underserved community.” |

In contrast, the Daniels Fund and Robert W. Woodruff Foundation had no references to equity in their materials, although each funds services for specific underserved populations. Neither used language related to systems change, with the one exception of Daniels’ program to reform public education. Both foundations rooted their mission in the intent of their original donors, successful businessmen who wanted to invest in key institutions and help the people in need in their home communities, yet didn’t seek to alter systems or power structures.

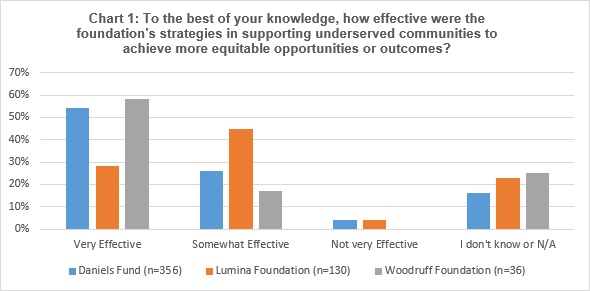

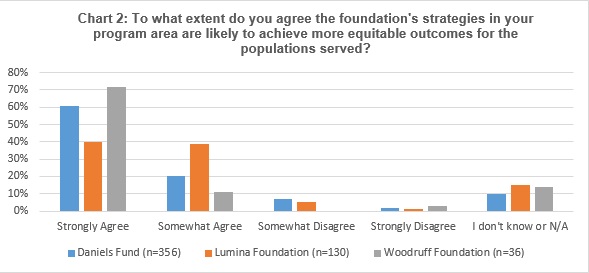

We asked grantees of each foundation how well the foundation’s strategies had already helped underserved communities advance equity, and also how likely their strategies would advance equity going forward. As these two charts show, the foundation with the most explicit equity goals, Lumina Foundation, didn’t score as highly as Daniels and William Penn. (Note that these questions were added after we had already concluded the William Penn assessment. Also, while we did not survey TCE grantees, who had already participated in a CEP Grantee Perception Report, most interviewees thought the foundation was making progress toward equity goals.) On the whole, however, grantees of all three foundations found them to be making progress toward equity goals, the main difference being whether they deemed them “very” or “somewhat” effective in this regard.

The fact that Woodruff and Daniels garnered more “strongly effective” responses despite the lack of an explicit equity lens to their grantmaking seems contradictory. This is especially true given that less than 10 percent of Daniels Fund grantees reported engaging in community organizing or policy advocacy, activities that seek to change systems. A quarter of Woodruff grantees engaged in at least one of these activities. In contrast, 47 percent of Lumina grantees engaged in policy advocacy.

As observed in PRE’s racial justice grantmaking assessments, even foundations with a desire to promote equity may not have a shared definition and analysis internally and with their grantees. PRE found that many of the grantees of the two foundations it assessed “tended to equate outreach to communities of color or diversity concerns with racial justice.” It’s possible that Daniels and Woodruff grantees viewed their own services to marginalized populations as advancing equity, since our survey did not spell out that NCRP sees “systemic change” as central to that goal. Or perhaps they saw Daniels and Woodruff exercising leadership on equity issues in ways that were not reflected in either their grant guidelines or their grant descriptions. Conversely, Lumina set a very ambitious and public equity goal—to achieve 60 percent college attainment by 2025. As a result, its grantees may have had a common understanding of equity, and they were more involved in trying to change systems. Perhaps, therefore, they held Lumina (or themselves) to a higher standard of success.

Interviews with each foundation’s leaders, selected grantees, peers, and other stakeholders were important to dig deeper and tease out complexities and contradictions in the quantitative data. For example, some Woodruff grantees, such as the Georgia Justice Project featured in Philamplify’s Woodruff video, were in fact engaged in systemic change to address inequity. These grantees typically viewed themselves as exceptions to the rule and often were not aware that Woodruff funded other groups like them. The lack of information from the foundation about its strategies, and its reluctance to assert public leadership on most issues (Robert W. Woodruff was dubbed “Mr. Anonymous”) left grantees, other funders and potential applicants in the dark as to its intentions.

Hence, while lack of an explicit focus on equity may not adversely affect the overall perception of effectiveness and impact, being overt allows prospective applicants, grantees, peers and other potential partners to understand what the foundation is trying to accomplish and how. And it enables the funder to measure its progress against specific objectives. Gita Gulati-Partee, author of the TCE report, also pointed out additional benefits:

- Having a more explicit theory of change around equity, i.e. systemic change that benefits specific marginalized populations, enables a funder to identify and invest in grantees that are each addressing different pieces of the puzzle, which is necessary to true systems change.

- It helps those grantees know about each other and potentially collaborate more effectively with others using different strategies toward shared goals.

- It allows the foundation to view itself as part of an ecosystem and be in more strategic relationship with other funders who intersect with their theory of change rather than going it alone, which by definition cannot achieve equity.

- It helps the funder use its leadership voice to influence the broader discourse, which also is needed to advance equity because it builds more allies for the cause and helps more people engage in understanding the problem and crafting possible solutions.

The California Endowment pursues all of these strategies and has experienced success at the policy level on issues ranging from health insurance access to school discipline. For the three foundations that did not have clear equity goals (or even systems change goals to benefit marginalized communities), NCRP urged them to do so. Philamplify recommended that Woodruff provide more grants and leadership to advance equity in Georgia; that the Daniels Fund support more advocacy and organizing to change systems for the populations Bill Daniels cared about, such as people with disabilities; and that the William Penn Foundation bring a stronger equity dimension to its environmental and arts portfolios.

Fast-forward to today, and some of the foundations we critiqued have decided that having more explicit goals makes sense. The Woodruff Foundation’s revamped website now makes clear that its strategies address systems change in health access and quality and in public education, although it doesn’t use equity language. And the William Penn Foundation recently announced $8.6 million in new watershed protection grants, indicating that the goal was public water access, “particularly in underserved neighborhoods that have been cut off from waterways for generations.”

What do you think? Should a foundation that serves a sizable non-white or marginalized population, whether because of its geographic locus or its issue focus, have explicit equity goals? Why or why not?

Lisa Ranghelli leads the Philamplify project as the director of foundation assessment at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @ncrp and #Philamplify on Twitter.