What a time-travel novel by Black sci-fi author Octavia Butler can teach us about making the case for justice when it feels like we’re taking two steps back

Dr. Tiffany Manuel

“That’s history. It happened whether it offends you or not.”

“You can’t come back all at once any more than you can leave all at once. It takes time. After a while, though, things will fall into place.”

― Octavia E. Butler, Kindred

In so many ways, our nation seems to be moving forward.

Last year, Ketanji Brown Jackson became the first African American woman to be sworn onto the Supreme Court. We’ve expanded awareness of the need for racial equity, renewing a focus on issues such as police violence and healthcare disparities as a result. And the whirlwind of commitments in response to the uprisings after George Floyd’s murder are a powerful example of how institutions can be made to see the case for equity, even as concrete action in response to these commitments has been lacking.

In short, there is much to be grateful for.

So, I find myself wrestling with how to square this recent progress with the Supreme Court’s reversal on Roe v. Wade and other recent threats to justice, including:

- Legislation weakening voting rights as we draw closer to the 60th anniversary of the 1965 march on Selma, AL

- Rhetoric and legislation that villainizes the teaching of our country’s shared racial history in schools

- Roll backs on environmental protection at a time when climate change is being felt in every corner of the country and, indeed, around the world

- Regressive tax policies that make it even tougher for most working families to make ends meet

Case making—narrative that builds the collective will for social change by tapping into people’s aspirations and hopes for the future—has won big gains on racial, gender, and economic justice issues in the past. But today, in a changed cultural environment, many gains have been challenged and, to varying extents, undone.

When it comes to Roe in particular, the case for reproductive rights that worked in the 1960s and 1970s—personal choice and the right to privacy—requires updating in our current moment’s cultural and political context. Roe’s reversal doesn’t obliterate reproductive options in all states—and voters in every state that put abortion rights on the ballot last November took the side of reproductive freedom. But we’re fighting to take two steps forward to recover from the court’s lunge backward, at a moment that otherwise feels full of opportunity and forward momentum.

With the stirring reproductive health wins of the midterms fresh in our minds, it is an important moment to ask: How do we strengthen our narratives for the long term? Are there ways to tell more durable stories about reproductive justice so we don’t have to repeat the past so often—not only with regard to reproductive rights, but the many important ways our country must move forward?

The answer is a resounding yes.

Traveling Through Time: We Need Octavia Butler in This Moment

Here’s what those of us making the case—that is, using narrative to get more people on the road to justice—need to know: When we seek to make social change, our ability to navigate time through the stories we tell not only makes our cases stronger and more durable. It also enables us to adapt these cases as circumstances change.

One of my favorite novelists, Octavia Butler, is a consummate storyteller, and the narrative approach of her award-winning book, Kindred, offers important lessons for strong case making. Dana, the novel’s main character, is a Black woman who is transported between the antebellum US South, where she is a slave, and her life in 1970s Los Angeles, where she is a successful writer. The jarring shift between those time periods and who she must be within them leaves Dana struggling to survive.

Kindred has much to teach those of us who are frustrated during periods of conservative retrenchment. Every day represents a new opportunity (and challenge) for us to overcome, requiring us to modify how we engage new audiences and pull them forward. Here’s what we can learn from Dana’s time-traveling journey in Kindred:

1. We need to learn how to navigate the changing political, social, and economic disruptions of our time

At the beginning of Kindred, Dana awkwardly moves between past, present, and future. By the end, she skillfully transitions between the violence of the past and her present life, and ultimately to the future, where her liberation was always waiting.

When we make the case for justice, we too must learn to move seamlessly between past, present, and future so that our case making becomes more durable over the long term—especially when it focuses on polarizing issues like abortion. We must learn to deal with the disruptions—political and demographic shifts, technological advances, unexpected opportunities, and challenges—that come with the changing seasons.

Most of us recognize history’s importance, but it takes practice to skillfully tell a story about the past that rallies people in the present toward the future. We must honor our past and speak honestly about it while doing the hard work that will get us to a better future. This takes practice and discipline.

We must also name the power of the moment to shape our future. For example, we can say something like:

Reproductive health shouldn’t be left to chance. We have to build durable healthcare systems that ensure we all have what we need to thrive. A culture that values health prioritizes people’s bodily autonomy and self-determination. If we don’t act now to ensure and preserve access to reproductive health resources, we’ll all lose essential health infrastructure. The health of our country is dependent on our ability to establish a culture of health and create a future where all people can live the lives they want, for themselves, their families, and communities.

2. We must tell stories that people can (and want to) see themselves in

Octavia Butler tells a story so vividly that we feel like we are in it. Every fight Dana fights, every argument she has, every injury she has to endure, whether verbal or physical, feels immediate and real.

To encourage more people to support your work, learn to tell a compelling story that they can see themselves in. This is especially true for tough stories about inequality, racism, and bigotry. Because when it comes to stigmatized issues like abortion and poverty, few people choose to be in these stories—let alone in the circumstances that necessitate their telling, whether it’s ending a pregnancy or deciding between making rent or paying for children’s school supplies.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

We should continue to tell personal stories about our experiences with abortion, poverty, and other difficult circumstances. These powerful stories spur empathy for the people behind these issues. But let’s not forget to make sure that, when it comes to events like the overturning of Roe v. Wade, the bigger point of our stories is about what greater access to reproductive health resources allows us to do—as individuals, communities, and a nation. Legal abortion allows people to better care for themselves and their families. It allows medical professionals to use the full range of their expertise to help their patients. And, given women of color’s high rates of maternal mortality, it saves lives.

Strong case making is about telling stories that invite people to imagine and want to be a part of a better world—one that helps families, expands the use of good medical expertise, and saves lives.

3. We must tell the story of justice as a journey, not a destination

In Butler’s Kindred, Dana is on a journey. She never arrives at a destination where the injustice she faced is eradicated. That makes her story dynamic and open-ended, which creates space for readers to imagine what comes next—and feel part of her journey.

Poet Amanda Gorman spoke powerfully about the idea of justice as a journey in “The Hill We Climb,” which she recited at President Joseph Biden’s inauguration.

Somehow we weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished.

We, the successors of a country and a time where a skinny Black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president, only to find herself reciting for one.

And, yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine, but that doesn’t mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect.

We are striving to forge our union with purpose.

To compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters, and conditions of man [sic].

When we position our work on the road to justice as Gorman describes it, we give people an opening to join us.

Say something like this:

Justice is a journey. For nearly 50 years, Americans were guaranteed the right to abortion. Though in reality, this right, and the ability to choose the composition of our families and the direction of our lives, has not been equitably available to all. Nonetheless, Roe v. Wade pushed women closer to equality, freedom, and justice. Our commitment today pushes us well beyond reproductive policy toward a larger opportunity to recognize people’s right to define for themselves who they are and who they will be, to live free of violence and fear.

Some people will deny the principled assumptions behind our work. Still, stories about justice as a journey—rather than a destination—allow people with broadly shared values to join the work wherever they are, and at any point along the way.

4. We must tell stories about systems through the eyes of real people

In Kindred, we experience the harsh brutality of slavery through Dana’s eyes. We meet villains, but we also feel the weight of oppressive systems through the novel’s depiction of everyday plantation life.

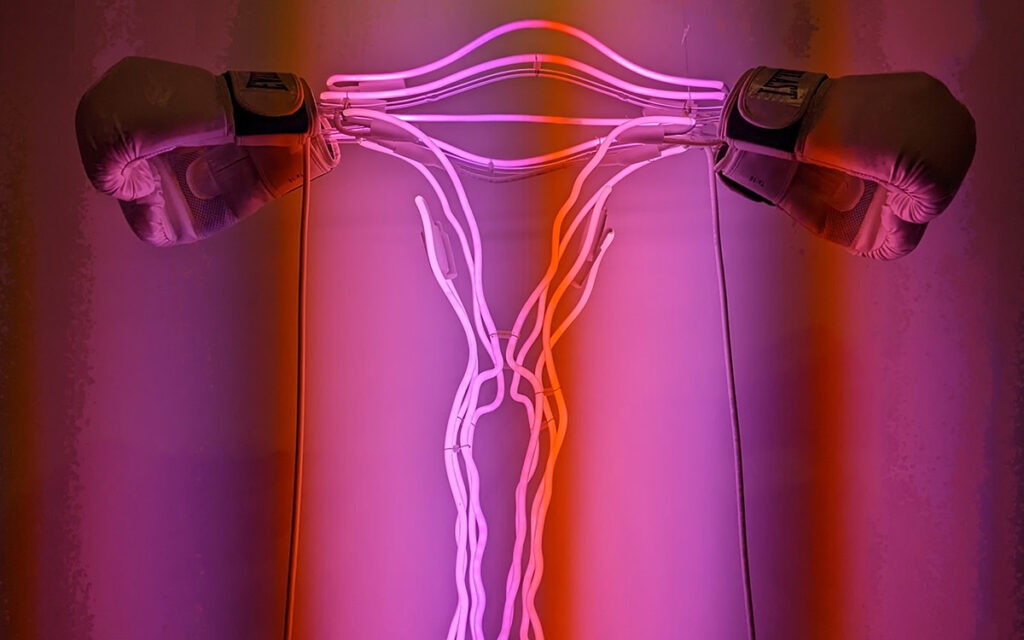

Our stories in the social justice field, including our stories about reproductive rights, need to reveal the systems that hinder people or help them. We often talk about abortion as an individual choice. Many people—cis women and men, trans and nonbinary and genderqueer people, too—have bravely told stories of the abortions they have had or supported a partner through. But the bigger story that connects these personal stories is how systemic change—in this case, creating safer access to abortion—enabled people to live fuller lives.

By broadening the conversation from individual choices to systems that enable healthy living, we can frame reproductive justice as an issue that requires systemic solutions that benefit everyone. Instead of lifting up the innumerable ways our health systems are falling short, let’s highlight what folks have done (or are willing to do) to make our systems operate better.

Researchers, for example, have found that states with a higher number of abortion restrictions have worse women’s health outcomes than states with fewer restrictions. They’ve also found that women in states with better reproductive health environments have higher earnings and better job choices.

So, it’s important to tell a systems story from the perspective of people whose lives have been improved because they had access to critical healthcare resources, then widen the lens to share how all our lives might be improved by expanding such access.

5. We must help people fully understand what they stand to lose if they don’t join our justice journey

In Kindred, Dana loses consciousness for minutes at a time. When she returns to consciousness, she must help her husband understand his stake in what’s happening to her. This dynamic is made even more dramatic because Butler has cast Dana’s husband as a white man who has difficulty understanding her journey into slavery as a Black woman.

When we make the case for social change, we face something similar. Most of us are trying to help people see their stake in our issues, when many of them have not experienced the harms that we’re fighting to eliminate and redress. Most people in our country haven’t gone to an abortion clinic, fought through a line of anti-abortion activists, and made the often gut-wrenching decision to end a pregnancy.

All of us lose something when women and trans people lose access to the healthcare they need, but most of us haven’t put our finger on what it is that we lose. If we can’t find a way to help those on the sidelines remember why and how this impacts them, we won’t be able to galvanize support for social and policy change.

We can bring people into the future by lifting up the ways that reproductive health technology and practice have advanced since Roe v. Wade was decided nearly 50 years ago. We’re not back to where we were then because new birth control methods have given people more choice over whether, when, and how they get pregnant and give birth, which expands their ability to contribute to society. If we lose these options, we lose the opportunity to create a more prosperous, equitable future for all. And to achieve a better future for all—one that goes beyond the right to an abortion—we must use all the tools that will lead us toward reproductive justice.