January 22, 2019; Wisconsin Public Radio and MinnPost

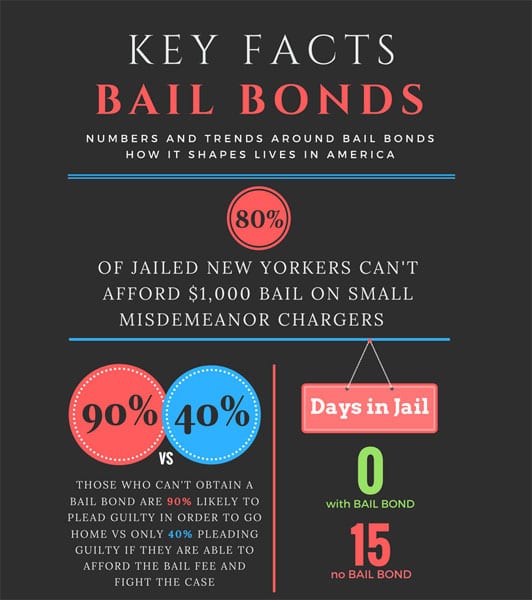

Originally, bail served as an incentive to encourage people to appear in court or forfeit the money. However, for many people, bail serves as a barrier to freedom and exoneration. In the United States, approximately 450,000 people per day (two-thirds of the national jail population) languish behind bars due to their inability to pay bail.

If being in jail for being poor isn’t punishment enough, individuals often experience greater disruption in other areas of their lives—job loss, eviction, and child custody battles are often the result. Furthermore, to escape inhumane conditions, people are more likely to plead guilty to a crime. Outcomes are even grimmer for those fighting a case behind bars. According to research from the Vera Institute of Justice, “Low-risk defendants detained pretrial are four times more likely to receive a prison sentence and three times more likely to receive a longer sentence compared with those released pretrial, even controlling for demographics and case characteristics.”

In response to this grave injustice, a growing network of charitable bail funds has begun to sprout up across the country. Founded in 2016, the National Bail Fund Network consists of over fifty community bail funds that use bail payment as part of a larger strategy to abolish money bail and pretrial detention. A newer initiative called The Bail Project aims to do similar work. In addition to paying bail, identifying clients, and supporting defendants through the legal process, the organization intends to establish 40 new sites nationwide and pay bail for 160,000 people within the next five years. The Bail Project expects to scale rapidly with financial support from the Audacious Project, a $400 million fund managed by TED.

While such highly visible groups as the Philadelphia Eagles have made sizable contributions to bail funds recently, funding largely comes from grassroot efforts. Most recently, activists Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba, visible leaders in the prison abolition movement, spearheaded #FreeThePeopleDay a grassroots fundraising campaign on Twitter. Supporters were asked to donate the price of one drink on New Year’s Eve to a local community bail fund. In just one day, over $233,000 was raised for bail funds across the country, allowing hundreds of people to be released and reconnected with their families in the new year.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Wisconsin is the latest to formally join the Bail Fund network.

Launched in August 2017, Free the 350 Bail Fund (FT350BF) primarily serves African American residents of Dane County (county seat: Madison) and has garnered support from many local progressive organizations, including Freedom Inc., Madison-Area Urban Ministry, Operation Welcome Home, Sankofa Behavioral Community Health, Madison General Defense Committee of the IWW, LGBT Books To Prisoners, and the National Lawyers Guild.

According to Jessica Williams, justice director of Freedom Inc., since last June the group has successfully worked to get nine people released on bail prior to their trials. According to the Vera Institute, Wisconsin has the 18th-lowest pretrial incarceration rate in the country. And while this would be viewed as successful in comparison to other states, glaring racial disparities show otherwise. In Dane County, African Americans comprise only five percent of the population but make up 48 percent of the incarcerated. FT350BF derives its name from this fact. In order to eliminate racial disparities in pre-trial detention, roughly 350 people would need to be released per day from Dale County Jail. While the group would like to pay bail for more people, the need exceeds their resources at this time.

Hopefully, upcoming bail reform may assist FT350BF in meeting its goal. Later this month, a state legislative study committee will begin reviewing proposals that would possibly reduce or eliminate bail as a requirement for release. Bail funds are only one tactic in a larger effort to end mass incarceration and organizers hope that Wisconsin’s pending bail reform will lead it to cease to exist. Robin Steinberg, cofounder of the Bail Project notes, “[Community bail funds are] designed to keep people out of jail who don’t belong there in the first place. If we get really, really lucky, I would hope reforms would put us out of business within the next five years, but it’s going to take a lot longer.”—Chelsea Dennis