Despite some progress in recent decades in reducing the overall number of people incarcerated nationwide, the United States easily remains a paragon of mass incarceration.

There are, at last count, some 1.9 million Americans locked up in federal, state, and county prisons and jails—a rate of incarceration that exceeds any in the developed world.

Across the United States, some 3.7 million people are under community supervision.

But even those staggering numbers belie a greater population of Americans who remain, in one form or another, under strict community supervision, with the threat of reincarceration hanging daily over their heads.

A new report by the Prison Policy Initiative has put numbers to that vast population and makes the case that those who purport to care about mass incarceration cannot ignore the scope and damage done to individuals and communities by its sibling, mass supervision.

Across the United States, some 3.7 million people are under community supervision, the report finds, with the vast majority (2.9 million) under probation and some 800,000 on parole.

“If the population under probation and parole alone were its own state, it would be nearly the size of Oklahoma.”

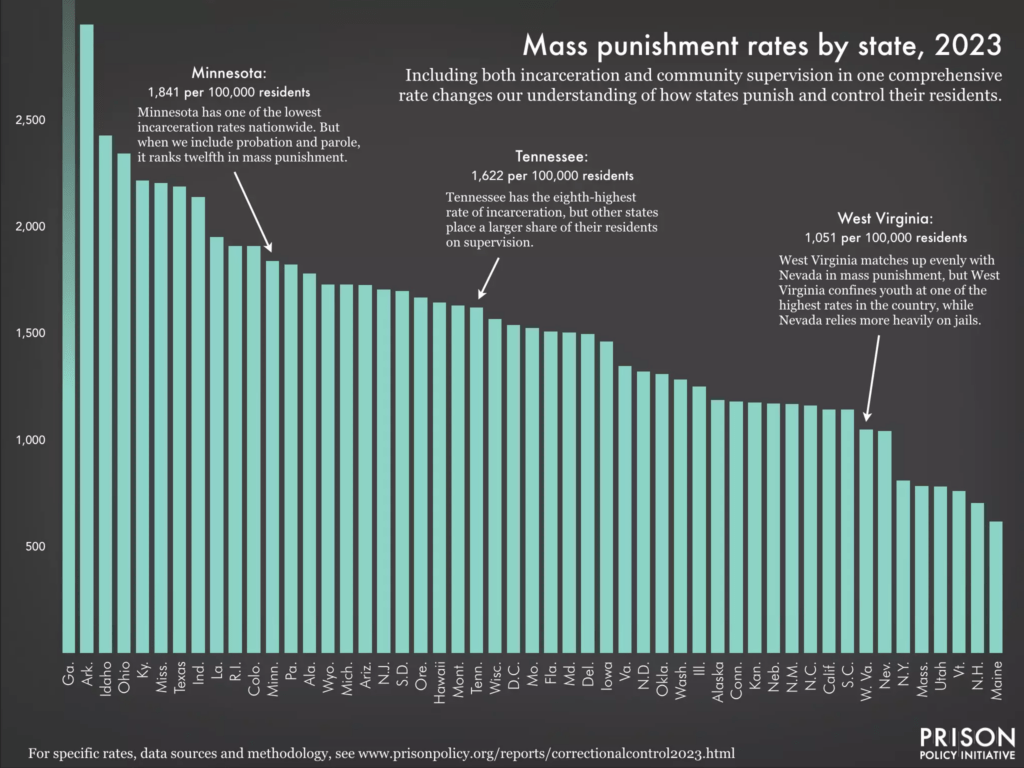

What’s more, in breaking down the numbers of those under community supervision by state, the report offers a view into the extent of the carceral system even in states considered more progressive, or which have claimed relative success in reducing prison populations.

Minnesota, for example, which has one of the lowest incarceration rates of any state, ranks twelfth among states in terms of overall “mass punishment,” as the report puts it.

In total, some 5.5 million adults in the United States are under some form of correctional control, the report finds: “To get a sense of how massive community supervision systems are, consider: If the population under probation and parole alone were its own state, it would be nearly the size of Oklahoma, and more populous than 22 other states, Puerto Rico, and D.C.”

And yet, the report notes, “despite the massive number of people under supervision, parole and probation do not receive nearly as much attention as incarceration. Policymakers and the public must understand how deeply linked these systems are to mass incarceration to ensure that these ‘alternatives’ to incarceration aren’t simply expanding it.”

Punishment Beyond Prison and Jail Walls

Increased attention and action around mass incarceration over the past couple of decades—including significant criminal justice reforms in many U.S. states—has arguably resulted in a more widespread understanding of the deep structural racial and economic inequities underlying the practice.

But the inequities and damage embedded in mass supervision have received far less attention, allowing supervision to go often untouched even as some states undertake reforms to reduce prison populations.

“There’s two problems,” says Wanda Bertram of the Prison Policy Initiative. “One is that we have a parallel crisis in this country of putting many times more people than are even in prison on probation and parole, which are systems that often replicate prison conditions in people’s communities.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“At the same time,” she continues, “we have another problem, which is that as awareness develops and as people put pressure on legislators to shrink the footprint of the criminal justice system, and in particular of prisons and jails, oftentimes probation and parole are floated as an alternative.”

Systems of community supervision, in other words, are often perceived as diminishing the carceral state, when in fact they might better be considered as extensions of it.

Those living under such supervision, Bertram argues, are not in fact “free” of the shackles of the carcel system.

“Supervision brings the long arm of the criminal legal system into people’s homes…When you are under supervision, you live under a different set of rules than anybody else,” says Bertram, noting that the average person on probation is required to comply with as many as 20 rules at once. Those rules can include work requirements, restrictions on travel beyond the state or even the county, mandatory sobriety, regular required reporting to often distant probation offices, and the payment of any number of fees for the supervision itself—fines many under supervision cannot easily afford to pay.

“And if you violate those conditions, you can go back to prison, even before you are found guilty of a violation,” notes Bertram. “You can be jailed simply because your parole officer says, ‘I’m accusing you of a violation.’”

Indeed, the PPI report notes that rates of “failure” for those on probation are so high as to call into question whether those being supervised are being given a fair shot at success at all: “These ‘failures’ are so common that less than half (44%) of people who ‘exited’ parole or probation in 2021 did so after successfully completing their supervision terms; the rest came off of supervision for unhappier reasons. Many people exit supervision when their status is revoked, usually after a violation, which typically means a period of incarceration.” (9)

Meanwhile, the onerous conditions of supervision can often work in direct opposition to the ability of those under supervision to achieve the very things most likely to lead to successful reentry.

“Supervision can actually make it harder for you to get a job, make it harder for you to find stable housing,” notes Bertram. “You may be attempting to get your life back on track and supervision can stop you from doing that, even though in theory it’s supposed to do the opposite.”

Shrinking the Carceral State

Some states have taken measures to reduce not just prison and jail populations but the greater number of people under community supervision like probation and parole.

“The greatest sin of mass incarceration is that it is racist.”

New York, for example, adopted the “Less is More Act” in 2021, a reform to parole laws that allows those under supervision to earn credit for time successfully served, effectively allowing them to cut significant time off of their supervision period. In the first year of the act, the state’s parolee population was reduced by 40 per cent.

And the overall population of those under community supervision has shrunk over the past two decades.

But advocates for shrinking the carceral footprint in the United States say that far more needs to be done across the states to focus not just on reducing prison populations but on reducing the number of people under the punitive thumb of the greater criminal justice system—not least because that system is now widely acknowledged to be classist and racist.

“The greatest sin of mass incarceration is that it is racist,” argues Bertram. “So, if what you’re concerned about is racist outcomes, and disproportionately Black people being funneled into that system, probation and parole are not going to solve that problem for you. You have to start thinking about how…you get people out of the system entirely.”