While many today have focused on the danger of a new US Supreme Court dominated 6–3 by conservatives, we must also recognize that the current state of leadership in the US attorney general’s office has helped create the problematic context wherein that court shift may occur.

“The most sacred of the duties of government [is] to do equal and impartial justice to all its citizens.” So wrote Thomas Jefferson, and the US Department of Justice (DOJ) has adopted this as its guiding principle, putting it front-and-center on its website. And, indeed, although the US attorney general serves at the pleasure of the president, the office is intended to function relatively non-ideologically to ensure constitutional rights and laws are applied fairly to all.

But at times this is an awkward balance, because the office is appointed by the president and ratified by the Senate. When they are in partisan lockstep, a path opens that allows the judicial system to become more a pawn of the executive branch. At that point, our rights and protections—individually and collectively—are at great risk, especially if these protections are disrespected by the president.

Let’s be clear, however; lock-step relationships between the president and DOJ are not the sole purview of Republicans. Certainly, some Democratic administrations have had challenges in that arena. But because respect for human and civil rights is a central mission of the DOJ, the risk of damage is high when judicial norms are set aside.

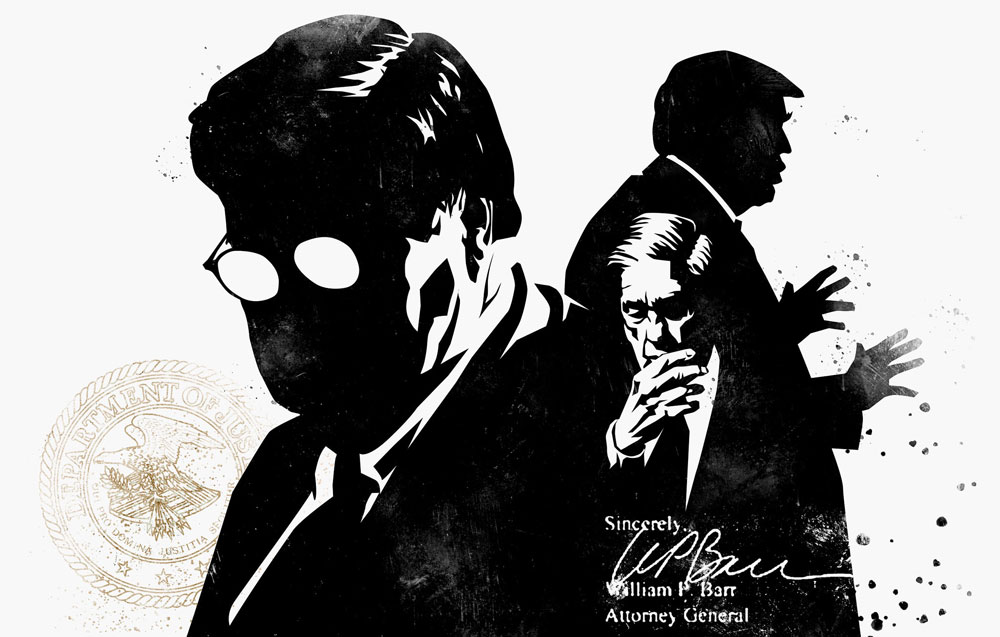

Heading down this partisan path with great zeal and fervor is US Attorney General William Barr, whose actions are leaving many to wonder what will, in the end, be left of our rights to free speech, to freedom of the press, free assembly, to free elections and more.

Barr is a “true believer” who in 1992 attributed the urban uprising in Los Angeles to “the general moral decline we see all about us in society.” He is also politically highly ideological, with a strong belief in a president with unitary powers. This combination can be very dangerous for our pluralistic society.

Background: What shaped William Barr?

Barr is the son of a Columbia University educator and headmaster of elite private schools. He was Jewish by birth, but he became a most enthusiastic Catholic. He grew up on the Upper West Side of New York City and studied at an elite private school himself where he, as a Catholic, was in the religious minority. He attended Columbia, where his views did not quite fit the counterculture and sexual revolutionary tenor of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

And then there was law school. Not a fancy Ivy League school, but a move to Washington, DC to attend George Washington University night school and then move into work at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in their office of legislative counsel. According to friends and others, this is where he developed his wariness of the CIA, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the National Security Agency, and their excesses. According to one aide, “He believes that the FBI and the national security state is powerful. It can be a force for good—and it can turn into the German Stasi,” the notorious Cold War-era East German security agency.

Barr’s work in agencies within the executive branch readied him for his service at DOJ. He served as attorney general under President George H. W. Bush, who had a more modest view of executive power than Trump. Barr was in semi-retirement when in June 2018 he sent an unsolicited memo to the DOJ, the White House Counsel, and others that outlined his concerns with the Robert Mueller investigation. In it, he made clear his own views of the “illimitable” powers of the presidency.

Barr’s views on a “unitary executive” found a receptive audience. Donald Trump reached out to him to step in following the dismissal of Jeff Sessions as attorney general and the short-lived time of Matthew Whitaker as interim attorney general. Barr was now in a place where he had the power to reshape DOJ the way he felt it should be, and he had the full support of the president of the United States in doing it.

Today, we are witnessing the results of this pairing of Barr and Trump. For Trump, the desire for connection to a legal consigliere can be traced back to his mentorship by the infamous Roy Cohn, who served as an aide to Senator Joseph McCarthy. According to Chris Cillizza of CNN, writing for The Point:

It was, in short, a deeply transactional relationship. Cohn taught Trump how to get attention and turn everything into a knife fight. Trump gave Cohn a high-profile public figure to create in his own likeness.

It’s that same sort of transactional nature that sits at the heart of understanding Trump and Barr. Trump has always longed for someone to provide legal backup to his ideas and views. (Cohn, Michael Cohen and Rudy Giuliani preceded Barr in that role for Trump.) Barr has always wanted a president who views the office as entirely unlimited in its reach and power. Each has found what that had been searching for in the other.

A Political Marriage of Perfect Symmetry

Some words and phrases are bantered about without really understanding them. The term “unitary executive” has its base in Article Two of the US Constitution, which creates an executive branch (separate from the legislative or the judicial branches) in which the president is in charge and runs everything. Put in fairly clear terms by Benjamin Wittes and Susan Hennessey, writing for the Atlantic:

The federal courts are divided regionally and stratified by the three layers of the judicial system—district courts, appeals courts, and the Supreme Court. Congress has two chambers, each with its own formal rules. But the American presidency is a single person. And the executive branch is little more than the people who work for him. There is a debate, of course, about how unitary the “unitary executive” really is, and that debate is wrapped up in a larger set of arguments about the scope and nature and limits of presidential power. But there is a core to the unitary-executive theory that is not in dispute: There is only one president, and he appoints the leadership of the executive agencies, who serve at his pleasure and thus must follow his direction or risk being fired.

With Barr and Trump sharing a belief in the unbridled power of the presidency, although perhaps not necessarily in just how best to use that power, the possibilities for fulfilling Barr’s quest for a potent “unitary executive” are in view. As noted by Manuel Roig-Franzia and Tom Hamburger in the Washington Post Magazine:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Theirs is a political marriage of perfect symmetry: a president who wants to do whatever he wants, whenever he wants—and believes he can; an attorney general dedicated to endowing Oval Office occupants with expansive power. In Barr’s thinking, the president is not the head of the executive branch of government, which is a collection of dozens of agencies and sub-departments. Instead, as Barr sees it, the president and the president alone is the executive branch. In word and deed, Barr is trying to make sure that it is Trump who will cement his vision of a nearly omnipotent presidency.

Consolidating the Vision of a Unitary Executive at DOJ

So, what does all of this mean in terms of what ordinary citizens see? If we start with what we saw and heard when Barr first took the lead at the DOJ in early 2019 and pre-empted the issuance of the Mueller report with his own “summary,” one could see some clues of what was to come.

Barr released his own four-page summary of special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential campaign—more than three weeks before publicly disclosing the full 448-page report. This gave the attorney general the ability to highlight Mueller’s lack of a conclusion on whether Trump obstructed justice while leaving out the details of 10 instances of possible obstruction of justice included in the full report. Barr also left out that Mueller found multiple contacts between Trump campaign officials and people linked to the Russian government. Trump was able to trumpet his “exoneration,” and Barr was able to support the concept of the unitary executive and the person now holding that space.

Even with the final release of the full report, his delay in sending an unredacted copy to the US House of Representatives gave appropriate (for Barr) cover to his president. What has occurred since seems to be the building of this unlikely partnership between Barr and Trump to use the levers of DOJ to expand and cement the powers of the president.

The attorney general has inserted himself into a number of areas that have raised eyebrows, if not hackles. Sometimes this has been in response to a presidential tweet, as in the case of the sentencing of Trump’s friend Roger Stone, when Barr recommended a lower sentence than that recommended by his own prosecutors. All four Stone prosecutors resigned from the Department of Justice in protest. Stone was convicted on seven counts, including witness tampering and lying to investigators in the Russia campaign interference case. The original sentencing recommendation was seven-to-nine years in prison. The actual sentence was 40 months, but Trump commuted Stone’s sentence before he served a single day in prison.

We can see similar actions (and reactions in terms of resignations) in Barr’s efforts to throw out charges against former national security advisor Michael Flynn, who had pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI, or trying to block the publication of former national security advisor John Bolton’s book, as well as the book written by Trump’s niece. Most recently, Barr’s asserted DOJ would replace Trump’s personal attorney’s in a defamation suit filed by E. Jean Carroll, who claims the president raped her in the mid-1990s. In this case, Trump will be defended by government attorneys (paid from the nation’s tax coffers) for an alleged crime that occurred years before he took office. According to Barr, “This is a normal application of the law, the law is clear, it is done frequently, and the little tempest that’s going on is largely because of the bizarre political environment in which we live.”

Legal precedent may be on the side of Barr and Trump on this one, and the defamation suit may be thrown out, but at what cost to the rest of us? There is a pattern here of Trump pushing a button and Barr responding, although Barr seems to be comfortable finding justifications in Article Two of the Constitution and the concept of the unitary executive.

New twists continue to set off constitutional alarms. For instance, Barr has become a zealot against voting by mail. At first, this was purportedly based on foreign interference, but Barr has since changed his tune. “Just think about the way we vote now. You have a precinct, your name is on a list, you go in and say who you are, you go behind a curtain, no one is allowed to go in there to influence you, and no one can tell how you voted. All of that is gone with mail-in voting.” And when you vote by mail, Barr warned in an interview, “There’s no secret vote. You have to associate the envelope in the mailing and the name of who’s sending it in, with the ballot.”

In short, Barr is creating the sense that voting by mail is more susceptible to fraud and will violate voter privacy and autonomy, assertions that have been debunked many times. Even now, the DOJ is supporting court cases to limit voting by mail. And Barr is joined in his election and voting concerns by Trump, who tweets and issues warnings and gloomy predictions as to what November 3rd portends.

In recent weeks, Trump has suggested he might not accept the results of the election if he did not win. He would not make a commitment to a peaceful transfer of power regardless of the outcome of the election, saying, “We’re going to have to see what happens. You know that. I’ve been complaining very strongly about the ballots. And the ballots are a disaster.” This echoes unsubstantiated arguments on widespread mail-in ballot fraud by Barr.

A second area that bears watching is Barr’s instruction earlier this month to prosecutors across the country to consider charging rioters and others who have committed violent crimes at protests with sedition. The idea of charging people with insurrection to overthrow legal authority (i.e. the government) is alarming. Adding to this, last week, the DOJ issued a list of three cities—New York, Seattle, and Portland, Oregon—that it deemed “anarchist jurisdictions.” They would be subject to cuts in federal funding, as they are places “that have permitted violence and the destruction of property to persist and have refused to undertake reasonable measures to counteract these criminal activities.” This, of course, is a boon to the president’s law-and-order campaign; all three are cities Trump has ridiculed in speeches and tweets. Barr justified this action in a statement accompanying the announcement:

We cannot allow federal tax dollars to be wasted when the safety of the citizenry hangs in the balance. It is my hope that the cities identified by the Department of Justice today will reverse course and become serious about performing the basic function of government and start protecting their own citizens.

In one of his speeches this month, Barr noted that the Supreme Court had determined the executive branch had “virtually unchecked discretion” in deciding whether to prosecute cases. All of this lends credence to his theory of the unitary executive and the power of the presidency. “The power to execute and enforce the law is an executive function altogether,” Barr said. “That means discretion is invested in the executive to determine when to exercise the prosecutorial power.”

What does this portend?

Barr seems to have achieved in a very short period of time what the Washington Post indicated was his hope in becoming attorney general: politicizing the DOJ to the benefit of one political party—the Republicans. While Barr has many individuals and organizations who support his ideology, he himself has never been a “joiner.” He aligns with the Federalist Society but was never a part of it in law school or his early career.

In Barr, we have the clever joining of a committed ideologue with a president who appreciates Barr’s ability to consolidate and manage access to power. There are many paths this pairing might follow. Few of them bode well for the integrity of the DOJ or the rule of law.