November 14, 2018; CityLab

At NPQ, we have regularly covered the way many companies get public subsidies when they relocate. Such economic development incentives, which often come at the expense of public school funding, now total as much as $90 billion a year. The recent tax incentives that Amazon is slated to receive for its soon-to-be regional headquarters of northern Virginia and New York City (and a new operations center in Nashville) are but the most recent example of a longstanding trend. Walmart, for instance, is estimated to receive over $400 million a year in such subsidies nationwide.

But what do you do if you’re running a big box retail establishment, your tax abatement period has run out, and you don’t want to move? Must you then, at long last, pay your property tax bill?

Not necessarily, reports Laura Bliss in CityLab. As NPQ has covered, hundreds of malls have closed in the past decade, with more likely to close in the decades to come. In northern Virginia, part of one mall was even converted into a homeless shelter. But how does this affect the property tax bills of malls that are still thriving economically? Well, as Bliss explains,

Big-box retailers such as Walmart, Target, Meijer, Menards, and others are trimming their expenses in a forum where few residents are looking: the property tax assessment process. With one property tax appeal after another, they are compelling small-town assessors and high-court judges to accept the novel argument that their bustling big boxes should be valued like vacant “dark” stores—i.e., the near-worthless properties now peppering America’s shopping plazas.

The way this is done is through the creative use of what are known in the real estate trade as “comparables.” As anyone who has ever had to buy or sell a property knows, what counts as a “comparable” is more of an art than a science. Still, as Jason Williams—the assessor for the city of West Allis, Wisconsin—points out, the level of creativity as to what companies seek to use as comparable properties can be astonishing. Pointing to a local Sam’s Club that seeking to have its active store assessed at the same rate as a mothballed store, Williams bemoans, “They’re literally using closed, boarded-up stores as comparables for a recently renovated, vibrant property.”

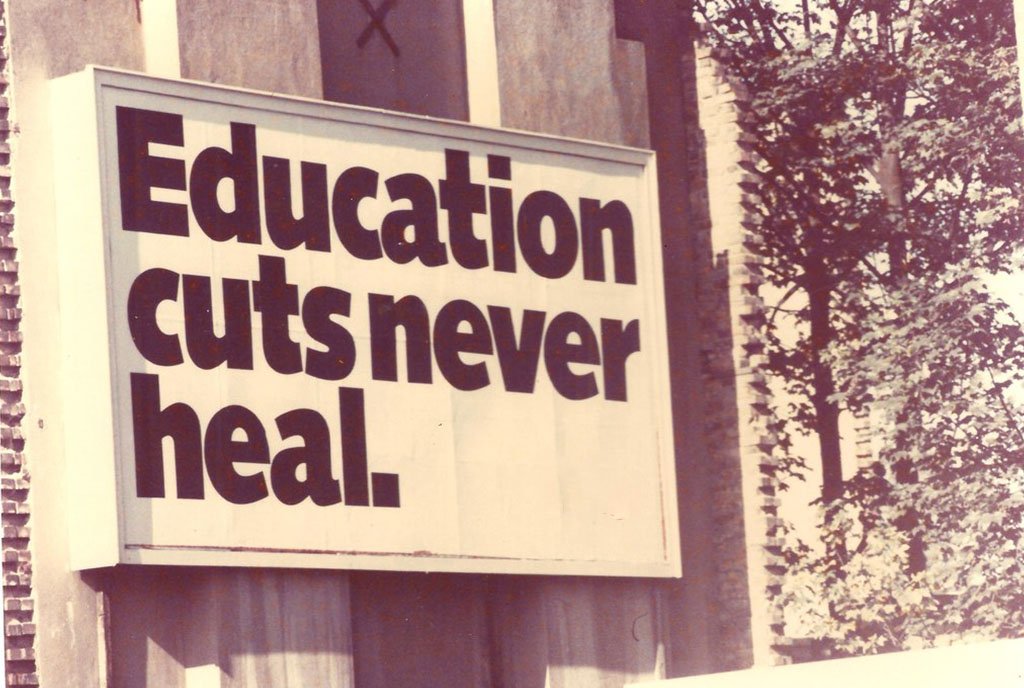

Bliss writes that success at tax reductions in West Bend, located 35 miles to the north of West Allis, “would reduce property values by millions of dollars, force the city to refund hundreds of thousands of dollars in back taxes, and set back payments on the public infrastructure that the town built to lure these retailers in the first place. That could result in higher taxes for residents, fewer police officers, firefighters, and teachers, and potentially, a mess of public debt.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“They are holding the communities for ransom,” Shannon Krause, the assessor in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, tells Bliss. Krause adds that Lowe’s, Nordstrom, Best Buy, Meijer, and appeal their valuations, year after year. “It’s a bleeding out.”

Wauwatosa and West Bend are two of the countless affected US communities. Bliss notes that, “A survey conducted by CityLab…found that these types of appeals have been filed in at least 21 US states over the past 10 years. The appeals likely number in the thousands.”

In Wisconsin, Bliss finds that 230 cases have been filed across 34 counties since 2015. In Michigan, Bliss adds, “more than $75 million in tax value was lost from the rolls from related appeals between 2013 and 2015.”

The stakes are high. “In Indiana, an estimated $3.5 billion in property value is on the line,” writes Bliss. Meanwhile, Bliss adds, “Texas stands to lose $2.6 billion per year if successful appeals become widespread, according to the Republican state comptroller Glenn Hegar.”

It is true, of course, that closures can affect the property tax values of the stores that remain open—some. But assessors note that there are many flaws in treating a property that is thriving the same as one that is not. “Do you want me to value your house as if it’s closed and boarded up?” asks Krause.

What happens in many cases is a whack-a-mole strategy. A company may ask for a 50-percent write-down, then settle for a 15-percent write-down. But that is just year one. “Retailers come back, year after year, insisting on paying less, even after they’ve been granted reductions,” notes Bliss. For the retailers, adds Bliss, “every demand brings the opportunity for a lower valuation, and there’s no real financial downside, with outside tax lawyers working for contingency fees.”

Meanwhile, while cites can win cases through carefully documenting the assessment process and showing that it is fair, the cost of legal defense is high. Krause notes that in Wauwatosa, repeat appeals from Lowe’s, Best Buy, Meijer, and others since 2013 have cost Wauwatosa $2.4 million in legal fees.—Steve Dubb