The 2017 version of Leading with Intent from BoardSource is a treasure trove of information about nonprofit board trends, but its purview is far too broad for us to manage in the context of one article. Therefore, NPQ will divide its coverage into a small series, with this first being the headliner. We mean for these pieces to further both exploration and action, so look for our webinar series that will launch next week in combination with BoardSource.

After a fraught last few years in terms of national attention to issues of race, one would expect that nonprofit boards would demonstrate at least a modicum of advancement in the realm of diversity. The comparative statistics shown in Leading with Intent: 2017 National Index of Nonprofit Board Practices tell a different story. Based on a recent biennial survey, any advances between 2015 and 2017 regarding the leadership positions of board chair and CEO were marginal ones. The proportionate number of board members of color even decreased slightly, as the number of groups with all-white boards increased from 25 percent of those surveyed in 2015 to 27 percent now.

What’s worse yet is that few if any boards appear all that concerned about the issue. As Vernetta Walker, Chief Governance Officer and Vice President of BoardSource, says, that’s unacceptable in a sector that purports to represent whole communities.

The 2017 Leading with Intent report provides an entire range of information that nonprofit leaders should find enormously useful, and we’ll go into those issues later. But, this particular set of findings should be considered a burning platform for nonprofits in 2017. While differences in respondents may have some impact here, at the very least, the picture shows stagnation over the past two years with little evident motivation to change.

The Findings on Nonprofit Board Diversity

Survey |

2015 |

2017 |

| Proportion of CEOs that are Caucasian | 89% | 90% |

| Proportion of board chairs that are Caucasian | 90% | 90% |

| Proportion of board members that are Caucasian | 80% | 84% |

| Proportion of boards that are all Caucasian | 25% | 27% |

According to the census, as of July 2016, white people (or Caucasians) who identify as neither Hispanic nor Latinx make up 61.3 percent of the population of the U.S.; add the Latinx-identified back in, and the total white population rises to 76.9 percent. (Latinx people were counted separately in the BoardSource study.)

The increase in the number of all-white boards is surely cause for alarm, but even more alarming is the low-priority status that boards have given to this longstanding problem. As BoardSource reports, 66 percent of the nonprofit CEOs surveyed are “somewhat dissatisfied” or “extremely dissatisfied” with the level of racial and ethnic diversity on their boards. Compare that with the 41 percent of surveyed board chairs who responded the same way.

In addition, as the report states, “Chief executive responses highlight an understanding of the many ways that diversity (or lack of diversity) can impact an organization’s reputation…80 percent of executives report that diversity and inclusion is important, or very important, to ‘enhancing the organization’s standing with the general public’ [as well as the] respect of funders and donors.” Seventy-two percent of executives report that diversity and inclusion is important, or very important, to “increase fundraising or expand donor networks.” However, among those executives who called themselves extremely dissatisfied, only 25 percent reported that diversity was a priority in board recruitment.

[clickToTweet tweet=”This change is necessary for your nonprofit’s survival. Does your board take diversity seriously?” quote=”Leaders like you have to make clear that this kind of change is necessary for the survival and effectiveness of your nonprofit. Focus on that idea; does your board take this precept seriously?” theme=”style4″]

“I am seeing more executives trying to push the envelope by keeping the issues on the table, but the problem isn’t always the executive,” says Walker, who works with many nonprofits as they try to work through a variety of issues, including their diversity and inclusion practices, “Quite often, it’s the board.”

Effective executives are constantly thinking about the changing environment and what their organizations need to change to make a difference, including the board’s racial/ethnic composition to more authentically represent the people they serve or to better understand different perspectives on issues they address. A homogenous board may not readily see or understand the impact of policies, practices, and decisions on racial and marginalized groups, or be willing to think differently about how it can create space for change—let alone take action. Chief executives can prioritize the issues, but the board has to step up for real traction.

In the organizations with boards that are entirely white, only 62 percent of executives feel that expanding the board’s racial and ethnic diversity is “important” or “extremely important,” and only 10 percent said diversity was a high priority in board recruitment.

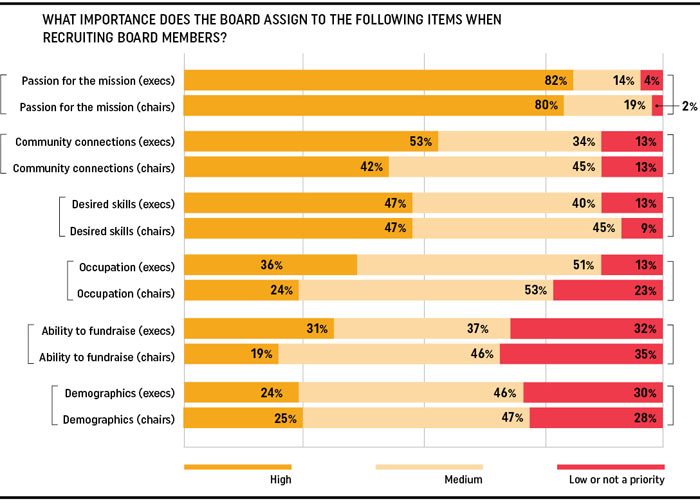

Long story short, though many boards and executives are wringing their collective hands, when it comes time to prioritize, ethnic and racial representation rank low on the list of important considerations. In a way, learning this is more distressing than it would be to hear that this issue went unacknowledged by nonprofit leaders. Instead, many do acknowledge it but don’t feel they must act.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There seems to be a powerful barrier to board resolve and action. But to have this article be more helpful than simple remonstration, NPQ has to acknowledge the risks inherent in starting a real inclusion process. The kind of unmentionable barriers to doing what’s needed require naming the problem. Can we talk about what’s in the way?

Frozen in Place: Seeking a Discussion of Undiscussables

Perhaps renown interaction sociologist Erving Goffman can offer clarity about what happens in the murky realm between human aspiration and human realities. In Encounters, Goffman differentiated between focused interactions and unfocused interactions. Focused interaction “occurs when people effectively agree to sustain for a time a single focus of cognitive and visual attention.” Unfocused interaction “consists of those interpersonal communications that result solely by virtue of persons being in another’s presence…while each modifies his own demeanor because he himself is under observation.” Goffman focused on encounters, or focused gathering; the spaces where we engage with each other. He wrote, “Encounters provide the communication base for a circular flow of feeling among the participants as well as corrective compensation for deviant acts.”

Goffman identified the key structure of encounters, or its order, as “what shall be attended and disattended.” He wrote that the general rule of an encounter is “the understanding that contradictory feelings will be held in abeyance.” This becomes a frame about what is discussable and undiscussable. In order to move a “pattern of properties” from the disattended (or the undiscussable) to the attended (discussable), the individual “breaks frame.” To do this, the individual relies on what Goffman termed “realized resources,” described as “locally realizable events and roles.” In this case, board members would be able to think about alternative actions and ways of being. This is a focused exploration of alternative board identities that have as a design a type of inclusion (both of content and people) that is ethically and strategically aligned with purpose.

Goffman proposed “transformation rules,” inhibitory and facilitating rules that modify the encounter such it that gives expression to a “pattern of properties” that has been heretofore externalized, or unattended. Goffman identified two key factors: who is allowed to participate, and how the realized resources are allocated among participants—that is, who gets to reshape reality and how. Attention must be paid to the “world prescribed by the transformation rules and the unreality of other potential worlds.” When these worlds overlap, there is ease…but when they don’t, there is tension, a result of the senses’ potential (and bigger) reality and the one in which the individual is “obliged to dwell.”

As content and feelings that have been externalized or unattended to start to figure in the encounter, incidents occur: “slips…gaffes, or malapropisms, which unintentionally introduce information that places a sudden burden on the suppressive work being done in the encounter.” These incidents must be perceived, accepted, and transformed for easeful use in the encounter. Goffman described this integration function this way:

By contributing especially apt words and deeds, it is possible for a participant to blend these embarrassing matters smoothly into the encounter in an officially acceptable way, even while giving support to the prevailing order…These acts provide a formula through which a troublesome event can be redefined and its reconstituted meaning integrated into the prevailing definition of the situation, or a means of partially redefining the prevailing encounter, or various combinations of both.

Finally, Goffman noted that all it takes is one individual not being “spontaneously involved in the mutual activity” to weaken involvement for others and “their own belief in the reality of the world it prescribes.” Ultimately, these transformations, from unattended-to events or possibilities to spontaneous involvement in a local version of a potential world, deal directly with identity. “Events which cause trouble do not merely add disruptive noise but often convey information that threatens to discredit or supplant the organizing identities of the interaction.”

In essence, addressing issues of racial exclusion means shifting the identity of the organization. According to the data, it appears this is a challenge for nonprofits. But, as Walker notes, the world is changing and has long been demanding more from nonprofit boards. Let’s start to move those barriers out of the way, so if some lag behind, they are recognized for the unhealthy stagnancy they represent.

What to Do

Moving for a moment to how boards can approach such a transformational shift, we might consider the three-step change model proposed by Kurt Lewin, who is credited with establishing group dynamics as a field of study. The first step requires overcoming inertia by dismantling an existing mindset, establishing the needed change as necessary to survival. The second and third steps involve the change process itself, which can be unsettling, and the conscious adoption of a new mindset.

Leaders like you have to make clear that this kind of change is necessary for the survival and effectiveness of your nonprofit. Focus on that idea; does your board take this precept seriously? Creating a “burning platform” for your board is the first step, and you should immediately start finding a way to do so.

What comes next will vary for different organizations. What we’re looking for here is no mere surface-level diversity, an actual identity change through an expansion of mindset. Over the next year, NPQ will work with BoardSource to provide models of change processes in the area of board diversity that have worked. Don’t wait around for that, however; instead, distinguish yourself by becoming one of those models.

A New Platform for the Work

BoardSource’s expert rendering of this odd combination of stated discomfort and intention vs. enacted focused commitment gives us all a better sense of the platform from which we must launch a serious effort to diversify the leadership in this important sector, and for that, we are all very grateful—and that gratitude should be expressed through action.

You can read the report for yourselves; there’s much more within that we’ll be covering over the next week. NPQ will continue this particular conversation about board diversity with BoardSource, starting on September 12th. We hope you will join us then.

Update: The final figures in the BoardSource report varied slightly from pre-release numbers. We have since updated to the most correct version.