The economic and social fallout from COVID-19 has prompted both domestic and international observers to call for building back more equitable economies.

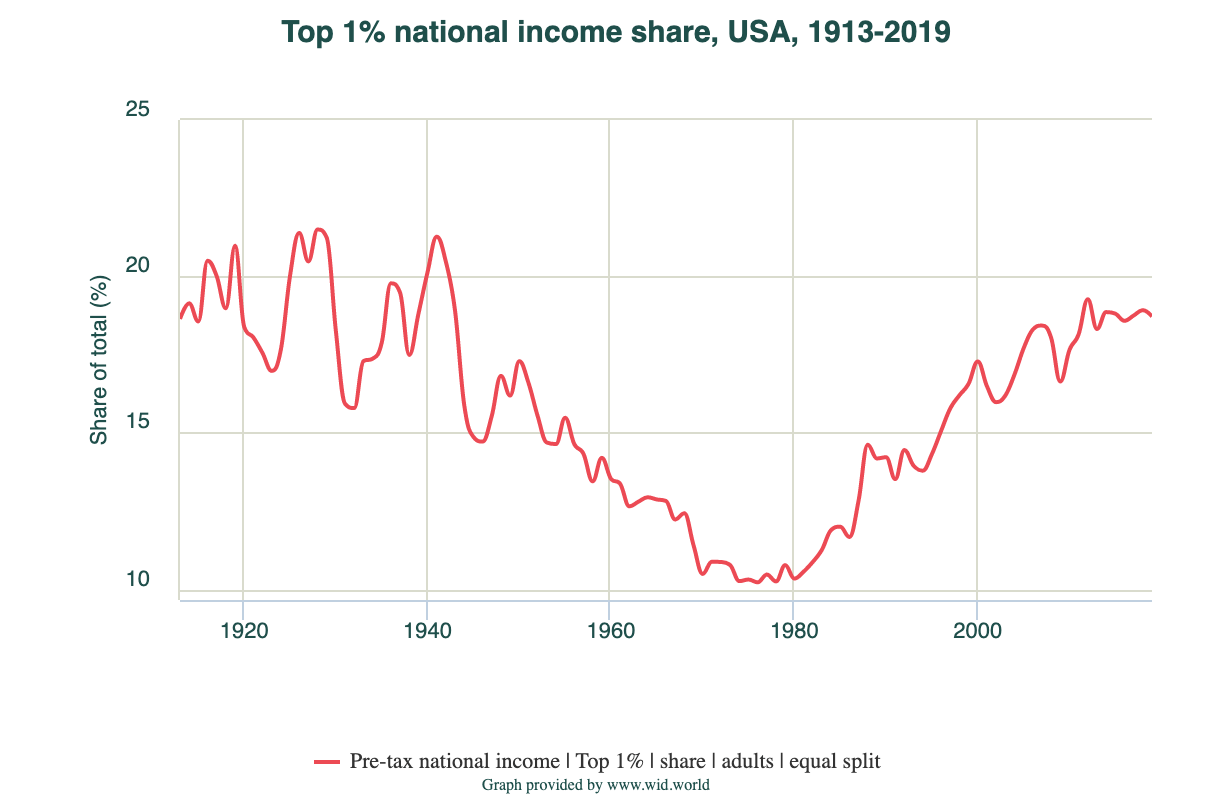

These calls are well founded. Income inequality in the United States is now approaching extremes not witnessed since the Gilded Age (see Figure 1). Vast inequalities also persist across nations, despite some improvement in developing countries in recent years.

Figure 1

The COVID-19 outbreak has only worked to exacerbate income inequality in the US, especially among people of color. As Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard details, “Federal Reserve staff analysis indicates that unemployment is likely above 20 percent for workers in the bottom wage quartile, while it has fallen below five percent for the top wage quartile.”

These facts have led many to call for building a more equitable post-COVID-19 society, with many observing that the structural racism and extreme class inequality evident in these numbers puts democracy at risk. But these calls often fall short in the details of how this can be achieved. Supporting social enterprise as a job creation strategy might provide an important piece of the puzzle.

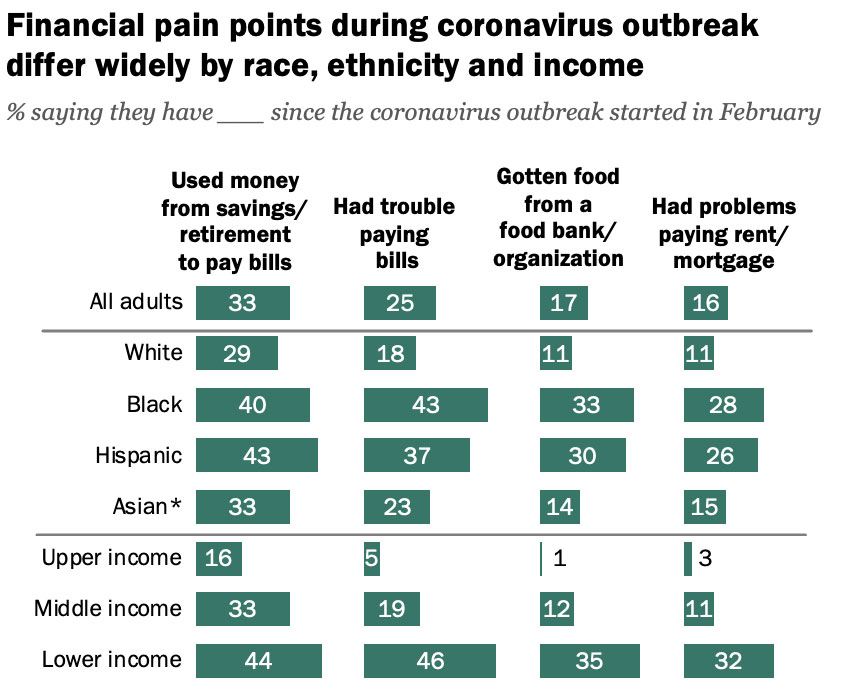

The rise in US economic inequality over the past four decades is easily documented. Indeed, the size of the middle class, in terms of adults living in middle-income households, has shrunk from 61 percent in 1971 to 51 percent in 2019. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated income inequality in the US by hitting low-income earners the hardest due to the vulnerability of their workplaces to closures, downsizing, and wage decreases. Moreover, many of these jobs disproportionately employ women of color. As result, the impact of COVID-19 reinforces class, gender, and racial hierarchies (see Figure 2). While economic relief packages provide cash payouts, unemployment checks, and support for businesses, the long-term effect of the COVID-19 economic downturn is not expected to be fully reversed for some time.

Figure 2

Some World Bank research via phone surveys in Nigeria, Uganda, Ethiopia, and Malawi found that by June 2020, 45 percent of workers had stopped work in Nigeria (17 percent in Uganda, eight percent in Ethiopia, and six percent in Malawi). It also found that urban informal jobs and women had been hit the hardest.

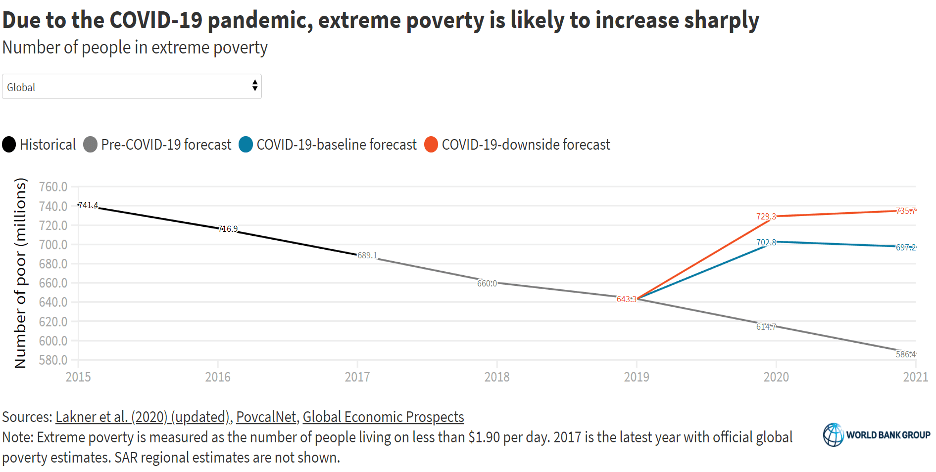

Figure 3

A recent British Council-funded report from Sub-Saharan Africa, however, suggests social enterprises can help meet the jobs challenge and reduce income inequality. Even before the onset of COVID-19, the availability of decent jobs across Africa was of major concern, with the continent’s burgeoning youth bubble being presented as both an opportunity but also a significant challenge. It turns out that, given support, social enterprises that use business models to address social challenges may be an important part of the solution.

What is a social enterprise? For our purposes, we draw on the definition used by the British Council report: First, to be a social enterprise, a business must generate at least 25 percent of its income through business earnings. Second, in terms of mission, a social enterprise must prioritize social or environmental impact ahead of (or equally with) financial profit. (Additional and more stringent criteria are often applied in countries with a more developed social enterprise ecosystem such as the United Kingdom).

Previous country-based research on social enterprise in Sub-Saharan Africa has highlighted the prevalence of social enterprises in certain countries (e.g., 55,000 in Sudan and a similar amount in Ethiopia). The majority tend to have been established in the past five to 10 years (64 percent of social enterprises surveyed in Kenya were set up in the previous five years), are led by people under 45 (67 percent in Sudan), and operate as a mix of legal entities (e.g., nongovernmental organizations or NGOs, cooperatives, private limited companies, and sole proprietorships). They operate across sectors such as social care, education, agriculture, and the creative industries— and they have a greater proportion of female leaders (42 percent in Sudan, 44 percent in Kenya) than their mainstream business counterparts. These reports have also pointed to a significant role for such enterprises in providing jobs.

The latest report, drawing on primary research across 10 countries—Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Ethiopia, Sudan, Botswana, Senegal, Cote d’Ivoire, and Cameroon—and including 67 key informant interviews, 44 focus group participants, and 1,840 survey responses, as well as secondary data analysis from across the continent, suggests social enterprise models support job creation in three ways:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- First, social enterprises were found to be delivery models for providing basic education, ensuring young people otherwise excluded from formal education systems are better placed to access work. Some social enterprises also provide content specifically geared towards social entrepreneurship and upskilling job creators, thus avoiding a common problem of workforce development programs of simply redistributing employment opportunities from one group to another.

- Second, social enterprises directly provide employment opportunities “from agriculture to education, from health and care to financial services.” Indeed, the research found that 78 percent of social enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa actively seek to create jobs compared to only 27 percent of “profit-first” businesses.

- Third, social enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa are supporting other businesses to create jobs, wherever they are along the business journey. The clearest examples are where social enterprises operate as incubators or accelerators, supporting others to set up or grow their businesses, or provide social franchising opportunities for others to replicate their business model.

All told, the British Council report estimates that 28 to 41 million jobs have been directly created by social enterprises across Sub-Saharan Africa out of 416 million jobs total—in short, between seven and 10 of every 100 people employed in sub-Saharan Africa work for a social enterprise. Furthermore, the researchers found that on average social enterprises employ 21 people compared to an average of two employees amongst small and medium-sized enterprises across the relevant countries.

The British Council report provides some examples. Many social enterprises are set up as training programs that also generate earned income to cover part of their operations. One social enterprise, the Clothing Bank in South Africa, trains 1,000 women a year to become self-employed traders. In Nigeria, Solar Sister trains women to become green-tech entrepreneurs. In Senegal, FraiSen aims to create 10,000 jobs in strawberry farming for young people by 2025.

There are US efforts that share some elements of these African models. For example, Accion’s southwest division boosts businesses in communities of color, providing loans, technical assistance, and financial coaching throughout a five-state region (Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas), with roughly 60 percent of revenues coming from earned income; to date, it has supported 9,000 businesses which employ about 19,700 people.

Beyond job numbers, two other strands of job creation are worth outlining from the report. First is the inclusivity of the employment created by social enterprises. Addressing the job creation challenge cannot simply be about creating more opportunities for favored subsections of society. Seventy-three percent of the social enterprises surveyed deliberately employ people from low-income communities and, although a subjective finding, 49 percent of the respondents said that if they did not employ them, their workforce would either be unemployed or working elsewhere in worse conditions and for less pay. Social enterprises also tend to perform well in terms of the number of women they employ. This study also found that 41 percent of social enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa have a woman in charge compared to 27 percent of mainstream businesses.

Secondly, social enterprises can be assessed in terms of the decency of work they provide. The researchers used three proxies for this: training opportunities, notice periods (notice given before layoffs), and levels of pay. With the first two criteria, social enterprises outperformed their profit-first counterparts. In relation to pay, the findings were less conclusive. Indeed, many social enterprises pay less than a living wage to their employees, but this is related to their size. While 32 percent of social enterprises with an annual revenue of less than £10,000 (about US $13,600), were found—based on a living wage indicator calculator—to pay living wages, 82 percent of social enterprises with over £10,000 in annual revenue did so.

If social enterprises create jobs, the report shows that this should not only be in terms of job numbers, but also the inclusivity and decency of work created. Here lies an important role for support agencies in enabling social enterprises to scale and reach a size where positive impacts are more likely to be realized.

A second report from the British Council offers a global snapshot. It suggests civil society intermediaries can provide powerful “opportunities to collaborate, and fora and networks to share best practice and build a collective voice.” This support can include financial backing for direct start-up and pass-through funding through incubators and accelerators that support early-stage social enterprises with funding and training. University centers and other nonprofits support everything from training to monitoring to certification and provide an important backbone for social enterprise activity.

Recent critiques from Sub-Saharan Africa point to the need to build more locally based networks, attract the right talent to access financing, and better connect rural and vulnerable entrepreneurs with existing groups operating in this sphere.

Financing mechanisms are the lifeblood of social enterprises. Such mechanisms are continually evolving, but most commonly include social investors who accept below-market returns, crowdfunding platforms, cooperative financial institutions, community savings groups, and venture capital trust funds (a fund of funds). Sub-Saharan African feedback here speaks to making midsize and late early-stage financing more available, simplifying requirements for small and Indigenous groups, and diversifying the actors involved in funding decision-making.

Finally, interrelated government programs and policies can support these initiatives. For example, tax exemptions and subsidies for social businesses, public procurement that favors such entities, social enterprise accreditation, tax relief for social investors, and grant funding for social enterprises including related training and research. While there has been movement on some of these fronts in the US and other countries, much more could be done in all of these areas.

Lessons and Implications

While Africa provides useful examples of social enterprise as a vehicle for supporting job creation, there are two key caveats. First, there is still significant room for improving the role of social enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa, and just as much might be learned from their challenges as their successes. For example, translating the creation of job opportunities into the payment of reasonable wages (thereby addressing income inequality) often proves unattainable for many smaller social enterprises. There is a role for ecosystem players to support enterprises to grow to a level where this becomes more possible. More developed social enterprise ecosystems may perform better in this respect. For example, in the United Kingdom, 2019 data showed that 76 percent of social enterprises were living wage employers, and the ratio of average wages of the highest and lowest paid workers was found to be just 2.7 to 1.

Second, job generation will vary across different contexts. Great care should thus be taken upfront to identify the appropriate supports necessary for successfully adapting African social enterprise models to different contexts. Support for social enterprise models should also work to build resilience in the face of instability. Drawing on global data, the second report from the British Council worryingly found that women-led and youth-led social enterprises have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

The above caveats noted, four lessons can be drawn from sub-Saharan Africa’s social enterprises that speak to both their accomplishments and challenges:

- Social enterprises can serve as vehicles to achieve the triple goals of education (both general and entrepreneurship), employment, and enterprise incubation.

- Social enterprises are often highly effective at helping disadvantaged groups address the symptoms and causes of structural inequalities. In the US, this approach to business could therefore provide particular hope for women of color and improved gender and racial equity.

- Civil society networks, finance mechanisms, and government supports should aim to bring social enterprises to scale so they can provide living wage jobs, vital for improving income equality.

- Ongoing feedback from stakeholders on the ground is needed, as it can help root out weaknesses, including in some cases a lack of representation of marginalized groups in decision-making around resources.

What is transferrable in the experience of sub-Saharan Africa to the United States? Evidently, the US provides a very different social and economic context. Also, in the US, unhelpfully the definition of social enterprise has often been stretched so thin as to constitute pretty much any business that mixes social value and profit components. At the same time, many businesses such as cooperatives that would be considered social enterprises outside the US, are, within the US, typically excluded from analysis.

However, as Accion and the many others demonstrate, at least a subset of social enterprises and nonprofits in the US serve a similar function of elevating the skills of workers of marginalized groups and enabling them to build their own businesses. In a COVID economy that has undermined the livelihoods of so many low-income workers and workers of color in the US, it may be time to give social enterprise solutions to job creation and economic inequality a hard second look.