Our greatest barrier is the scarcity of money. Or so we have been told.

Charitable giving had a record-breaking year in 2020 at $471.44 billion. Yet, in 2021, but for the notable exception of Mackenzie Scott, donations towards initiatives benefiting Black and Brown communities weren’t a priority for the nation’s top 50 donors. What’s more, $1.3 trillion sits in the corpus of foundations, and donor-advised funds (DAFs) total close to $160 billion. The wealthy individuals who give to these foundations have already received tax deductions for their donations, yet most of these funds are, at least for the time being, invested in stocks, bonds, or hedge funds, with only a small percentage reaching social justice groups.

Again, lack of money is most assuredly not the problem. The top one percent of US earners continue to accumulate enormous wealth—the nation’s billionaires saw their wealth rise by $2.1 trillion between March 2020 and October 2021. But consistently, those who hold this wealth have opted not to provide movements with the resources they need. For example, two years ago, the Washington Post looked at the 50 wealthiest Americans, who had a combined collective net worth of $1.6 trillion, and “found that their publicly announced donations toward COVID-19 relief efforts amount to about $1 billion, which is less than 0.1 percent of their vast personal wealth.” In other words, the overwhelming majority of the wealth generated at the top is being hoarded, rather than being invested in philanthropy of any sort, let alone racial and economic justice.

The silver lining is that community leaders are creative, making use of philanthropic resources where they can, but figuring out other ways to resource their communities when philanthropic funds fall short. In the past year, we have connected with many such Black and Brown leaders who are trailblazing new economic interventions through the social finance intermediary, Possibility Labs, which we co-lead. These leaders are experimenting with solutions that aim to replenish our scarce resources by nurturing relationships and subverting the systems of oppression that hold all of us back. Below, we offer vignettes from four movement organizations that are changing the landscape by developing inspiring, community-led models that build power, wealth, and social justice.

Communities Not Commodities

Nikishka Iyengar and her colleagues at Groundcover—a project and forthcoming fund of the Atlanta-based worker-owned cooperative, The Guild—build community wealth through community-owned, equitable real estate; business development programs focused on cooperatives and other small businesses; and access to capital. At times, this mission can feel overwhelming. Iyengar believes, however, “How you do it is as important as what you do.”

Groundcover’s pilot project is a community-owned, mixed-used property—a 7,000-square-foot commercial space that has been abandoned for nearly a decade in a gentrifying, historically Black neighborhood. The project is financed through a combination of money from investors supportive of a solidarity economy who provide low-cost capital, along with community shares that are priced low ($10 to $100 a month) to be accessible to community residents. The goal is to restore the building’s economic viability through a community ownership model. The co-op is expanding the property to 21,000 square feet by constructing two additional stories. The building will include permanently affordable housing, a grocery store bringing high-quality provisions to a food desert, a community gathering and co-working space, and three small commercial kitchens to scale restaurateurs without brick-and-mortars.

Groundcover is designing and planning the property in collaboration with community members—often starting design sessions by asking them, “What are y’all wanting to see out here? This project is going to be owned by you all.”

As Iyengar explains, “The current, top-down, charitable giving model—where mostly white, wealthy donors give to Black and Brown communities—neither builds up the self-determination of those communities nor tears down existing power structures that keep them locked into the status quo. It doesn’t get at any root cause analysis of how we ended up here in the first place.” Iyengar continues, “If you leave the same systems in place and just improve access to the same systems, you are going to end up with the same results.”

Groundcover’s pilot project is structured to build wealth and power for Black and Brown communities. When construction is complete, the property will move into a community stewardship trust, and anyone in the zip code can buy shares of the property for as little as $10. All profits generated will be returned to community investors rather than developers. Community investors will be paid back through annual dividends and the property’s appreciation. Further, the property is taken off the speculative market so it can’t be sold for the highest dollar in the future.

Healers Get to Heal

Ain Bailey is the founder of New Seneca Village (NSV), a nonprofit retreat space for women and gender-expansive BIPOC social justice leaders. During her inaugural residency, Bailey is using her “free-time” to support 37 leaders who work on a range of issues, from housing and economic justice to Indigenous land rights, policy advocacy, and more. As the program grows, more leaders will be invited to “come together in gorgeous nature, share with one another, and lean into their own restorative practices.”

The group Bailey founded is named after Seneca Village, the 19th-century multicultural community founded by free African American landowners and later destroyed to make way for New York City’s Central Park. The group’s mission is to foster spaciousness, a sense of connection, and collective restoration while allowing each leader reprieve from the persistent grind of justice-focused leadership. Alongside lodging, food, time in nature, and connection with a network of changemakers, each leader may access up to $1,000 for transportation in addition to $1,250 for child-care, elder-care, pet-care, or any other “back-home” costs that would keep them from exploring or re-engaging with restorative practices.

Bailey is fortified by her confidence that abundance is possible. Practices that support this vision include salary parity, transparency, and community governance, with organizational plans calling for NSV to be governed by a board of BIPOC leaders. Future goals include building a restoration-centered village on land stewarded by a mission-driven land trust, co-created with the Indigenous community on whose land it is located.

A BIPOC Venture Fund

Visible Hands began with a mission to support BIPOC and women tech entrepreneurs; combat bias in the investment world; and build generational wealth in historically overlooked communities. When the group’s general partner, Daniel Acheampong, learned that only 10 percent of all venture capital went to people of color or women, he thought of his three sisters: “If any one of them were to build a company, the chances of them becoming successful gets significantly diminished by virtue of gender and color.”

Acheampong and co-founders Yasmin Cruz Ferrine and Justin Kang are entrepreneurs of color themselves and created a BIPOC-oriented venture capital fund that aims to change these statistics. To do so and form Visible Hands, they tapped their networks, as well as corporate racial justice funds created in the summer of 2020, to create a fund that can engage BIPOC and women entrepreneurs at the earliest stages of their startups and support them through a 14-week accelerator program to ensure a generous flow of financial, social, and inspiration capital. The group automatically invests $25,000 in all founders accepted into their program. Through a SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) structure, Visible Hands receives a modest 2.5 percent equity share in each founder’s startup. As founders get more traction and maximize profits, they have an opportunity to receive up to $150,000 in additional investments.

The accelerator program, which operates virtually and supports 35 founders, surrounds each founder with mentors and peers at the most isolating stage of building a startup. Amirah Raveneau-Bey, a member of the accelerator cohort and CEO and co-founder at The Home Dispatch says, “The step-by-step personalized structure of ‘let’s solve a concrete problem in your business’ is the reason why Visible Hands is special and just totally different.”

Acheampong says it is not difficult to find entrepreneurs of color who merit investment; traditional venture capitalists don’t find them because the criteria they use to determine who is worthy of investment is biased. Acheampong notes that this “can be as stark as: ‘This person is white. This person is young. They probably went to an Ivy League school. They were able to get $200,000 to $500,000 from friends and family. They’ve been able to get a ton of users on their product. This is probably a good investment. Maybe this is the model we should always look for.’ That’s why 70 percent of venture capital dollars go to white men.” Acheampong recognizes that burgeoning Black, Brown, and women tech entrepreneurs are often the friends and family for their own communities and do not have generational wealth to give them their start. With the social, inspirational, and financial capital that Visible Hands provides, underrepresented founders will have a strong foundation upon which to build future investments and grow their innovations.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A New Kind of Community Loan Fund

The Kheprw Integrated Fund (KIF), created by Kheprw Institute, is a charitable investment fund designed to bridge the gap between capital markets and community wealth building. Kheprw weaves together empowerment, education, and economic and environmental interventions to build self-determination, self-actualization, and self-mastery for Black and Brown communities. The life force behind the 20-year-old institute is team of parents, grandparents, and others with a commitment to family, community, and nurturing.

Co-founder and Executive Director Imhotep Adisa lives on the Boulevard Campus where Kheprw owns three properties that serve as dormitory and virtual meeting spaces during the pandemic. Most of Kheprw’s conversations with community members and funders happen on his front porch. He describes just how much trust goes into connecting recipients to their trust-based loan fund:

Last night, a couple of community members came by the porch. One young lady who’s been with us about a year got fired from her job on Monday and was not in a good place. We huddled and said, “Get her over to the porch every day this week.” She came over. She’s looking for a job. I took a piece of my budget—as small as it is—and said, “Okay, your job is to go to this conference and interview people for our community wealth building stewards.”

While she was here, we had a member from the arts council, who came up and said, “Do you guys think we can collaborate on providing some bridge capital for artists who get projects with us but don’t have the dollars to put the project together before they get paid? Can we talk about the Kheprw Integrated Fund to support local Black and Brown artists?”

So, I said, “Well, how much money is it?”

They said, “Oh, maybe $4,000 every six months.”

I said, “I’m sure we can have a conversation about how to support artists in our communities.”

While they were sitting there, the young lady was on the porch. She is an artist and studied financial management. The arts council person said, “We have an internship available—20-30 hours a week. We’re looking for somebody who has some financial background.” So out of that relationship, we connected her to an opportunity that significantly improved her mental health.

As Adisa summarized, “That’s a day in the life—and it’s not separate from living. It’s a way of living and being. But culture is maintained through institution building. We’re creating an infrastructure and institution that allows us to live and model our vision.”

When asked whether things have gotten easier or harder after two decades, Adisa laughs. “You mentioned white supremacy, and hell is always hard,” but that hasn’t stopped the work. “Anytime that I feel like it’s getting too hard, I go back into spaces where I have even less of a voice—organizations that are controlled by white males, or places where it is difficult for people of color to bring about authentic change.” He adds, “After I do that a couple of times a week, back to my front porch.”

Shifting From “Programs” to “Ownership”

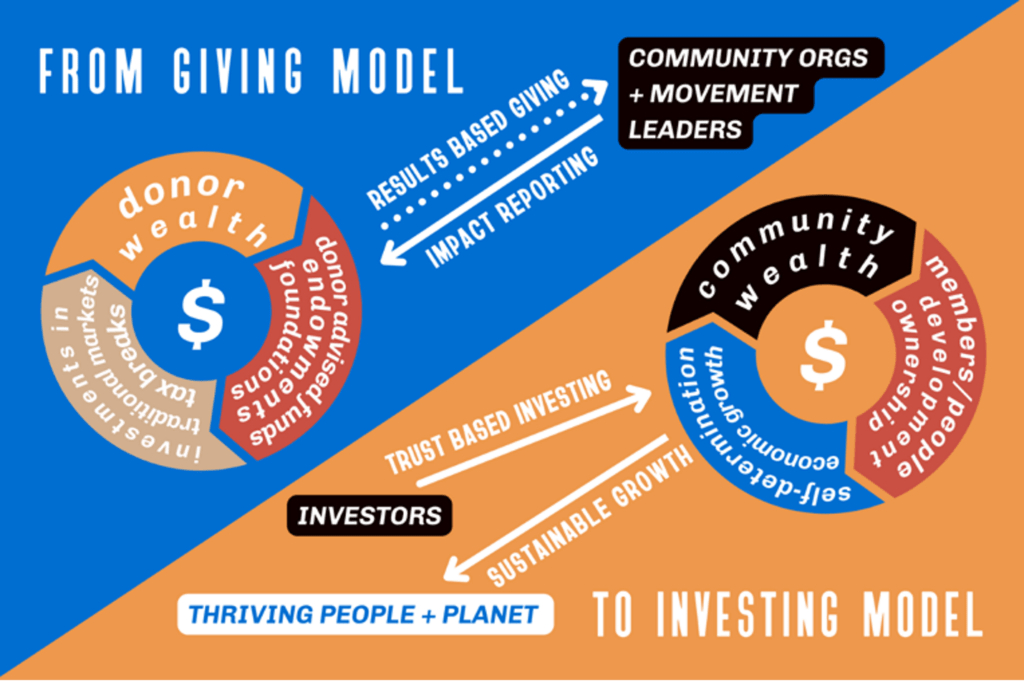

The four vignettes above provide some snapshots of what is possible. These leaders are addressing complex problems with comprehensive long-term solutions—their organizations exemplify the importance of building trust over time and the racial healing that is necessary for sovereignty. They also reveal the importance of shifting philanthropists’ and activist’ mindset and practice. As illustrated in the graphic below, this means a shift from a “giving” model to an “investing” model, or, in other words, from a “program” model to an “ownership” model.

Another tool to enable movement organizations to build community ownership and community wealth is to restructure the way transactions between philanthropy and nonprofits occur. As the above chart illustrates, this means shifting from a model based on philanthropic grants and donor reporting to a model that focuses on building the long-term wealth-generation capacity of the movement group. For example, a $600,000 contribution over a three-year period is typically deployed at $200,000 per year with an “intent” to contribute $600,000 in three years. However, an “intent” is different from a “commitment.” While an “intent” allows recipients to book only $200,000 each year, a “commitment” enables them to book the entire $600,000 on their balance sheets in the first year, attracting more funding from other investors by improving organizational balance sheets.

Organizations must also adopt innovative technology and capacity-building tools so they can receive and deploy larger investments to experiment with more complexity and agility. We’ve witnessed many “no’s” under the guise of “what you want to do is too complex,” not because of what organizations want to do, but because data integration and automation systems don’t exist in instances where transparency and real-time data are necessary for responsive fund administration or other resourcing initiatives. Designing such systems requires significant investment and time. But those investments are critical to freeing up time for strategic community power and economy building work.

Co-creating a just world is not a dream anymore. It is already happening. Instead of focusing on figuring out how communities can self-govern, it is important to recognize that BIPOC communities are already self-governing. The real challenge, however, is, How do we challenge the status quo instead of maintaining it?

To build a new economy where all people and the planet can thrive requires accepting greater risks. For those in philanthropy, this means changing with and for movement leaders now.