Last December, NPQ senior editor Steve Dubb asked a critical question: Does investing with “good intentions” make any difference in saving the world? The data clearly imply that, at least so far, the answer is “no.” Despite exponential growth of impact investing over the past decade, wealth inequality, conflict, and global heating have only worsened. Is impact investing merely, as critics like Winners Take All author Anand Giridharadas contend, another tool of wealthy “philanthrocapitalists” making more money while assuaging their guilt?

In fairness, impact investing has achieved some impressive results. Its stated goal is to marshal the humongous power of market capital. If successful, it could offer a strong foundation on which to build a better world. That architecture, however, remains fuzzy. This article aims to help fill in the blueprint and, through a proposed set of principles and list of actionable ideas, address some of the core building blocks for constructing not just an efficient industry but a broad-based movement that could support social justice through markets.

The Sobering Reality

A critical starting point is acknowledging the severity of the problem with our current economy. Despite epic branding, the US hasn’t been the land of opportunity for decades. The $7.25 federal minimum wage is now more than 25 percent below where it was in real terms half a century ago.1 For social mobility, we are barely in the top 30 industrialized nations. Our children fare worse with each passing decade; a child born into poverty in Denmark is four times more likely than an American kid to exceed the well-being of its parents.2 We remain the only industrialized nation without national health coverage. Private sector unions have been decimated. A quarter of Americans are without retirement savings, and our sacred homeownership rate has dropped towards the bottom of developed countries.

The past few decades has led to unconscionable wealth inequality, with the US having the greatest income inequality of all G7 countries (the others being Germany, France, Great Britain, Italy, Canada, and Japan). Globally, nearly half the world’s population still lives in debilitating conditions, on less than $5.50 per day.3

Perhaps cognizant of growing unrest at the bottom, leading global corporations issued a letter last year acknowledging that profit had become too much of a sole fixation, at the expense of workers and the planet. And yet, as scrutinized by a Ford Foundation-supported study4 and attested to by a BlackRock senior executive, this appears to have been little more than a public relations effort.

The Need for a New Vision

Clearly, impact investing should not have to be a silver bullet for all of these ills. It is reasonable, however, to expect that a serious social impact model would provide at least a vision for moving out of this morass. Yet, one is challenged to find a vision within impact investing that moves beyond a focus on growth and modest reforms.

I am offering therefore an outline of principles based on alternative values. This is not easy. Roots are deep, and deeply tainted. Capitalism has emerged out of hundreds of years of extraction and exploitation. The underlying assumptions of scarcity and individualism have become gospel to many.

Yet, here we stand, “impact investors,” seeking to do what activist-author Audre Lorde described as impossible: using “the master’s tools” to construct something different.

Is the field willing to engage in a robust discussion regarding what impact investing might look like with a different set of starting assumptions? And how do we make this “just transition” to a new and regenerative economy?

A vision of truly transformative finance would balance legitimate concerns of productivity, efficiency, and profitability with tenets of equity, distribution, and mutual aid. In a beautiful article and podcast describing the natural world’s “economy of abundance,” author/scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer, a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, offers a powerful analogy via forest ecology.

Fortunately, such discussions are gaining traction, at least in marginal progressive circles such as the Racial Justice Investing group in which I am involved. The proposed principles reflect therefore what I have heard directly from impact investors, and from themes emerging from more humane schools of economics and human development. In sum, they speak to establishing the appropriate role of capital in strong partnership with a well-functioning state and active citizenry. Here are the principles in summary form:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Capital must serve the people and planet: Healthy and sustainable investing must occur within the context of an economy and capital markets ecosystem that exist primarily to serve the people and the maintenance of a healthy and sustainable planet—not the other way around. (See Manfred Max Neef.)

- Partnership: Capital markets must work in effective and accountable partnership with government, philanthropy, nonprofits, and frontline communities.

- Government funding: Capital must support good government supported by progressive taxation that reduces burdens for low-moderate earners and that taxes wealth and corporations more than income and individuals.

- Full cost investing: Each investment must minimally “do no harm,” with screening and application of ESG (environment, social, and governance) as a starting point—see IFC’s 9 Principles—and account for full costs/risks of the investment—i.e., pricing externalities.

Already, there are snippets sprinkled throughout impact investing that allude to moral high ground and just aspirations. These require elaboration and should be imbued with real meaning. This involves reimagining markets beyond even ESG, the impact investing yardstick, and indeed beyond capitalism as we know it, fixated as it is on monopoly, shareholder primacy, and profit maximization.

Within impact investing, there is a good amount of innovation, and major field builders like the GIIN (Global Impact Investing Network, the field’s leading trade association) are working to shift the social impact valuation from operating at the margins. It seems that a good starting point for support and the advance of this important work is building consensus on a shared set of principles.

From Principles to Actions

How do such values get translated, however, into pragmatic action? (In short, “what is to be done?”) And how does one make meaningful reforms in the midst of a very broken system?

The prospects for changing such powerful forces are daunting. Fortunately, there are an abundance of concrete models to inspire and inform us. The Scandinavian experience reminds us that not all markets perform with such barbarism. Indeed, the “Nordic Model” nations, even if imperfect in some ways, consistently top the “world happiness index” and HDI (Human Development Index) indicators. Even the US was much closer to experiencing balanced growth and prosperity following the New Deal and President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and, up through the early ’70s, backed by decades with high taxation on the rich and corporations. Other diverse countries sharing this celebrated economic status possess similar features of better performing markets and social democracy. In sum, there is ample evidence of potentially transformative ideas that have existed for more than half a century and have been successful in numerous countries, as well as in earlier US history.5

Taking Action: 12 Steps

So, if markets can and do vary, what role can impact investing play in changing contemporary US and G-7-style capitalism? Here are 12 steps the field can take:

- Advocate for economic justice: We can as a field affirm our commitment to support union protections, good jobs, full employment, racial and gender equity, immigration reform, progressive taxation, balanced trade, appropriate regulation, social insurance and health care, public investments in infrastructure and human capital, education and childcare, safeguards against corporate abuse of power, and climate policy.

- Agree on principles: A draft slate of these is offered above.

- Challenge the contradictions: Apply the agreed-upon principles more strictly to our own operations.

- Embrace community wealth: Particular focus here should be on innovative business models like worker cooperatives and community land trusts that broadly distribute ownership and are driven by purpose.

- Prioritize social returns over financial returns: To address the common argument that concessionary returns hurt pensioners, perhaps a “tiered return” system could prioritize those on truly fixed incomes, while still reducing the overall yield to enable investments to achieve their highest impact.

- Embrace reparations: Challenge the denied legacy of and unearned benefit from historical injustice and stolen assets. Although still nascent, it is heartening to see within the impact investing space a few concerted and explicit efforts towards reparations—such as the Southern Reparations Loan Fund.

- Support major investments in climate: Advance legislation that curtails fossil fuel use and massively invest in ecology—from renewable energy sources to biodiversity, green construction practices, ecotourism, and forest diversity.

- Commit to movement building: Impact investing’s positioning as a true social change vehicle requires solidifying key alliances with social movement groups like Sunrise, Movement for Black Lives, and others.

- Adopt a global perspective: We’re in this together. Obviously, many issues, notably the climate crisis, cannot be addressed adequately otherwise.

- Be prepared to question our own lifestyles: This is a challenging and personal discussion; but frankly, it is hard to promote social justice-oriented investing while still holding on to an elite lifestyle that drives participation in contradictory activity. While no one is pure, actively cultivating a higher bar for what we deem impact investing seems to be a necessary step in our movement.

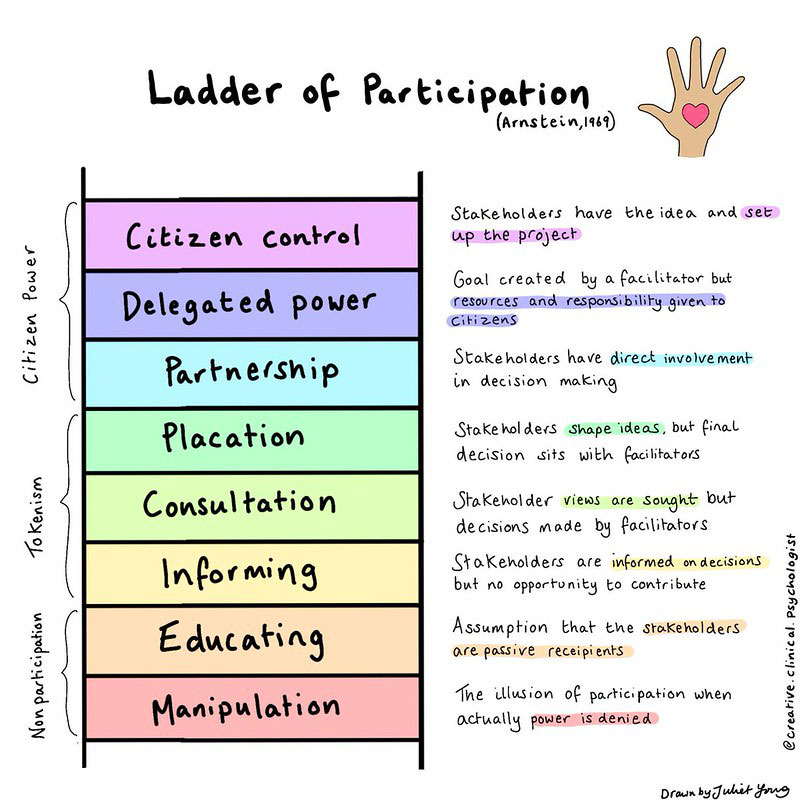

- Center those who are impacted in decision-making and power: Ultimately, the breadth and depth of the transformation we seek will be determined by the extent to which power is shifted. A true embrace of democratic governance means that no longer will “we” be making decisions on behalf of others, but centering the voices of impacted, frontline communities.

- Champion a well-functioning state: The final recommendation here underscores a point made towards the end of Dubb’s article where he notes the need for impact investing to stop ignoring the vital role of the state. While it may be obvious why a well-functioning state is critical for responsible investing, perhaps it is less so why impact investing must support government in nurturing democracy. Yet without accountability and transparency in government, it will be impossible for impact investing to alter the economy’s current trajectory.6

Perhaps the lack of attention to the state in impact investing reflects the elitist orientation of our field, i.e., the comfort that our resources and social capital will protect our rights and access, even as others more vulnerable than us suffer. However, as outlined above, a well-honed state and market dedicated to equity and opportunity can create regenerative possibilities that benefit us all.

Conclusion: Learning from the Past

Part of what drives me to fertilize the social justice roots of impact investing is a desire to do better than what many of us in the 1980s, and our predecessors in the ’70s, did when we advocated for divestment from racist South Africa. Yes, we were instrumental—along with international partners and of course the heroic struggle and sacrifice of the people of South Africa—in breaking the back of apartheid. Yet, South Africa’s political economy is now a poster child of what not to do, sporting the highest inequality in the world. A country of phenomenal wealth, laden with gold and diamonds, has a poverty rate of 50 percent. In our well-intentioned struggle, our demand for socially responsible investment was necessary but not sufficient. Our call for “one person, one vote” probably should have added on “one share.”

The continued economic prosperity of markets wrapped in democratic finery maintains the glitter of these uneven, unhealthy states. Not surprisingly, South Africa joins the US, India, Brazil, Mexico, and Russia as global industrialized leaders in COVID, inequality, and vulnerability of the poor. If we are to continue to believe in impact investing and the power of markets for social justice, we must affirm principles and build a movement that reacts in horror to the current state of affairs, builds an economy on principles of abundance and collective well-being, and isn’t bedazzled by the trappings of wealth. Our eyes must remain on the prize of justice and equity.

Notes

- “Policy Agenda,” Environmental Policy Institute, December 2018.

- “Chapter 5: A Family Affair: Intergenerational Social Mobility across OECD Countries,” from Growing for Growth, OECD, p. 187.

- “Nearly Half the World Lives on Less than $5.50 a Day,” World Bank, 2018

- Peter S. Goodman, “Stakeholder Capitalism Gets a Report Card. It’s Not Good,” New York Times, September 22, 2020.

- Shared prosperity flourished prior to the enforcement of integration when, as Heather McGhee describes so well in her new book The Sum of Us, the pathology of racism superseded material self-interest. Explicitly to deny any public investment in Black people, common white folks supported the sacrifice of their own major public benefits, namely quality public education but also public swimming pools and other amenities.

- Michael Brush, “Now there’s a way to invest and save democracy,” MarketWatch, March 6, 2017.

Millard “Mitty” Owens, Principal at Community Impact Consulting, was a PRI (program-related investments) officer at the Ford Foundation, directed microlending at Self Help, and helped lead the NYC Office of Financial Empowerment. He is an Advisor to the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies and can be reached at: info2communityimpact@gmail.com.