Who pays? Along with its companion question of “who benefits,” “who pays” has long been a central concern of both politics and economics.

Earlier this year, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) published Who Pays: A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States, its seventh study on the topic since 1996 and its first since 2018.

State and local tax policy tends to get less attention than federal taxes. In part, this makes sense. After all, most people pay more in federal taxes. But that does not mean state and local taxes are insignificant. In 2021, state and local taxes combined totaled $4.1 trillion—36 percent of the average American’s tax bill.

Typically, state and local taxes are far more regressive than federal taxes, meaning that they usually worsen economic inequality rather than lessen it. That said, the ITEP report makes clear that progressive state and local tax policy is possible, a finding that has important implications for federal tax policy as well.

What Is State Taxation Like Today?

In 2021, state and local taxes totaled $4.1 trillion—36 percent of the average American’s total tax bill.

While progressive state and local tax systems are possible, regressive policy remains the norm. Today, in most states, wealthy people pay considerably less as a percentage of income than working-class people. Consider the following summary statistics:

- On average, across the 50 states, those in the lowest 20 percent pay, as a percentage of income, 60 percent more than those in the top 1 percent. As a result, state and local taxes eat up 11.3 percent of income for the poorest 20 percent, while the top 1 percent pay 7.2 percent of income.

- In the 10 most regressive states, those in the lowest 20 percent pay three times as much as a percentage of income than those in the top 1 percent.

- In 41 states, the top 1 percent of households pay the lowest tax rate of any income group.

The percentages tell some, but not all, of the story. What does this mean in dollars and cents? According to ITEP, the average income of a US family in the bottom 20 percent is $13,600 a year. If these families paid 7.2 percent of income in state and local taxes (as the top 1 percent pay) instead of 11.3 percent, their after-tax income would increase by $557. By contrast, the average income of the top 1 percent is $1,889,900. If these people paid 11.3 percent of income in state and local taxes (as the lowest 20 percent pay) instead of 7.2 percent, their tax bill would climb by $77,485.

What Drives State and Local Tax Regressivity?

The fact of state and local tax regressivity is fairly well known. But why does it exist? The biggest reason has to do with how state and local governments raise revenue. There is a lot of variation, but nationally, state and local taxes are almost evenly split into three main forms: 1) property taxes (34.4 percent), 2) sales and excise taxes (34.2 percent), and 3) trailing sightly the other two: income taxes (28.8 percent)—with the remainder (about 2.5 percent) coming from other sources (royalties, license fees, and the like).

Both sales and property taxes are highly regressive. Sales taxes are particularly regressive. Fundamentally, this is because sales tax is assessed on consumption; people with low incomes spend almost all of their income and, therefore, pay sales tax on nearly every cent they earn. Meanwhile, wealthier people save more and spend less as a percentage of income, and thus pay proportionately less tax.

The differences add up. According to the ITEP report, families in the lowest 20 percent of earners pay 7 percent of their income on sales and excise taxes; those in the middle 20 percent (households earning between $45,900 and $80,400) pay 4.8 percent, while those in the top 1 percent (households earning $737,400 or more) pay 1 percent of income in sales taxes. What gets taxed also matters. For instance, one of the most regressive forms is a sales tax assessed on groceries.

Property tax might seem progressive, but it is still highly regressive, albeit not to the same degree as the sales tax. Nationally, ITEP reports that low-income families pay 4.4 percent of their incomes toward property taxes, middle-income families pay 3.1 percent of their incomes, and the top 1 percent pay 1.9 percent.

Why is this? First, because affordable housing is scarce, landlords are often able to shift property tax costs onto renters. In other words, renters may not get a tax bill, but they still pay property taxes. There are also other reasons. One has to do with the fact that many forms of property that are held mostly by wealthy people, such as stocks and bonds, are exempt from property tax entirely. Another reason: as covered in NPQ earlier this year, assessment of property systemically overtaxes low-income households while failing to adequately tax high-income households.

The state income tax, by contrast, does tend to be progressive. On average, ITEP reports that low-income families pay 0.2 percent of their incomes toward state and local income taxes, middle-income families pay 2.4 percent of their incomes, and the top 1 percent pay 4.1 percent.

Florida and Texas aren’t usually considered “high-tax” states, but if you are low income and live in those states, they are.

But income tax is only progressive if the rate and deduction structures are set up so the rich pay more. A dozen states have “flat taxes,” where there is no progressivity. Deductions that primarily benefit the wealthy, such as lower rates on the sale of assets (capital gains), can also reduce progressivity.

How Low Can You Go?

As the authors of the ITEP report point out, depending on the income level you consider, your conception of whether a place is a high- or low-tax state may change.

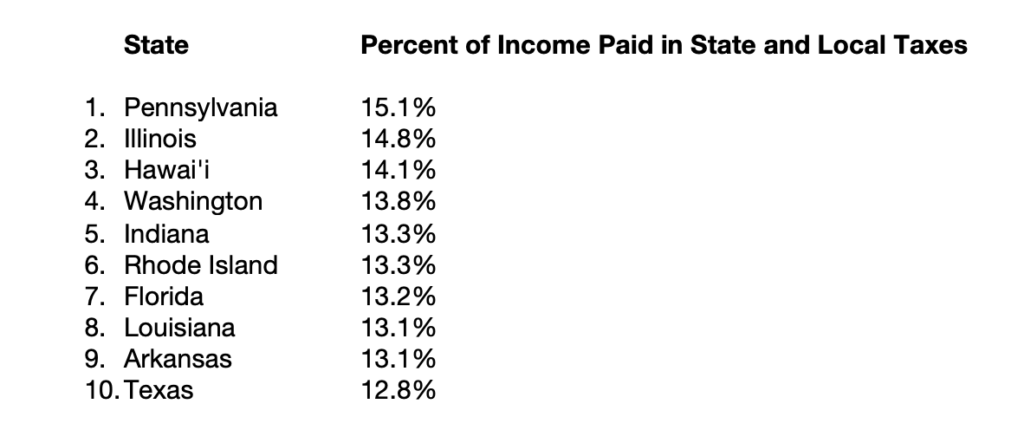

For people with incomes in the lowest 20 percent of households (earning $23,500 a year or less), the top 10 highest-tax states are as follows:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Florida and Texas aren’t usually considered “high-tax” states, but if you are low income and live in those states, they are. On the other hand, if you’re in the top 1 percent in Florida, for example, state and local taxation averages 2.7 percent of your income—less than one-fourth the rate the state’s poorest residents pay!

It’s worth noting that the above list consists of four “blue” (heavily Democratic) states, five “red” (heavily Republican) states, and one “purple” state (swing state—in this case, Pennsylvania). Tax systems that harm the poor are rather bipartisan.

A Progressive Path

Can state taxation be progressive? The good news is that, according to the ITEP report, progressive state tax systems are possible. What’s more, this marks a change from the recent past. In 2015, when ITEP published its fifth report, the authors wrote, “Every single state and local tax system is regressive.” This is no longer the case.

This year’s report finds that six states (Minnesota, Vermont, New York, California, New Jersey, and Maine) and the District of Columbia have shifted to modestly progressive tax systems. To be sure, the level of progressivity in these states is limited. Still, it’s an important shift from a decade ago when no one was at that level.

In the District of Columbia, which is listed as the nation’s most progressive jurisdiction, the lowest 20 percent of income earners pay 4.8 percent of their income in District taxes—far less than the numbers cited above. Meanwhile, the top 1 percent pay 11.4 percent of income in District taxes—four times the level paid by their Florida counterparts. Importantly, these tax rates appear to be sustainable—the exodus of Washington DC elite to Florida is conspicuous in its absence.

So, if a more progressive tax system is possible, how do you do it? A few policies are key:

- Implement an income tax system that assesses higher rates to higher earners. For example, Massachusetts has moved from the 17th most progressive state in 2018 to the seventh most progressive state in large measure because state voters approved a higher tax rate for millionaires in 2022

- Use tax credits, such as state child tax credits, to buttress the household income of low-income families

- Limit deductions on income taxes that benefit the wealthy

- Reduce reliance on sales and excise taxes

Greater tax progressivity…depends not only on who wins the 2024 elections but…on the level of organizing that takes place.

In the ITEP report, Minnesota was singled out as a state that had shifted in recent years toward a more progressive tax system, part of a broader political shift in the state that was the product of years of organizing. As the report authors explain, some key policies were “enacting tax increases on corporate profits and high-income families, including those with large amounts of investment income. It paired those tax increases with larger tax credits for low-income workers and families with children.”

The authors add that the “the net effect has been to lift the incomes of the state’s poorest families by more than 2 percentage points, while raising taxes on the state’s most affluent households by 0.3 to 0.4 percent of their income. For Minnesotan families in the lowest income quintile, who saw the level of state and local taxes they owed fall from 8.7 percent of income in 2018 to 6.2 percent, the rate difference works out to close to $500 in additional after-tax income.

A Federal Opportunity

At the end of the 2026 calendar year, many provisions of the 2017 tax law, which significantly reduced the progressivity of the federal tax code, are set to expire. This creates an opportunity, possibly, to build a more equitable and progressive tax structure in its place. This is true because if nothing happens, the tax cuts expire. This creates “leverage,” as Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) notes, for advocates of a fairer tax code to force changes simply by blocking the extension of existing tax rules.

Whether a shift toward greater tax progressivity occurs depends not only on who wins the 2024 elections but also, as in Minnesota, on the level of organizing that takes place between now and then to build power to achieve progressive outcomes.

Earlier this year, Emanuel Nieves, Jeremie Greer, and Solana Rice wrote a report published by Liberation in a Generation that cites the expiration of the 2017 legislation as a “rare opportunity for full-scale tax reform that could be leveraged to make our economy fairer.”

A fairer tax code, they add, is a critical step on the path to building what they call a liberation economy—one that “serves the basic needs of people of color” and creates “a sense of inclusion, belonging, and full economic citizenship.”

The organizing challenge to achieve that vision remains immense. It is no secret that the tax system favors the well-connected. The good news from the ITEP report is that at the state and local levels, a fairer tax system appears both politically winnable and economically sustainable. Advocates of a more progressive federal tax code would do well to learn from these examples.