May 23, 2019; Richmond Times-Dispatch

For decades, nonprofits and their funders have been looking at programs that appear to function well in one setting and imagining how they would scale on a larger level. In “Why Programs Get Replicated,” an NPQ article by Peter Frumkin and David Reingold, the authors talk about problems with replication that flow from inadequate research, but many other problems come from geographical, cultural, political, and local market differences, and these create questions that complicate the movement of a model from one place to another. Still, there are ways to avoid some of the common pitfalls.

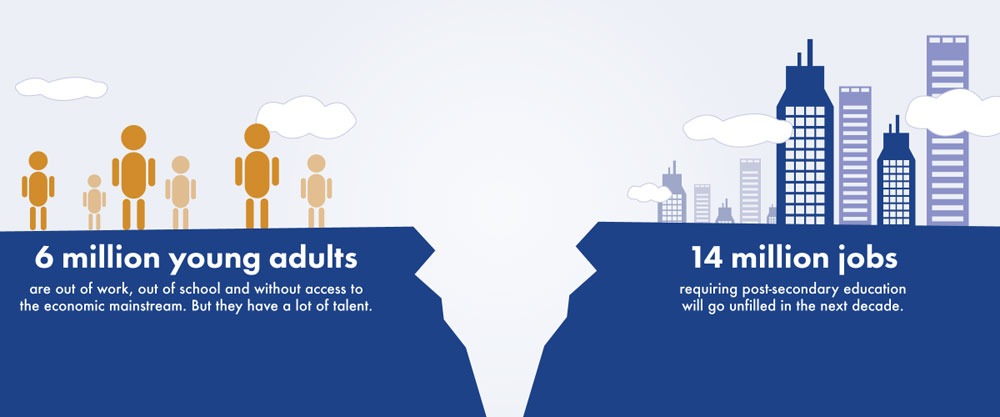

Byron Auguste, the CEO of Opportunity@Work, calls tech jobs “the new manufacturing jobs” because they offer an opportunity for economic security. Nonprofit organizations play important roles here, both in teaching needed skills and in connecting schools, students, and employers. Successful programs are showing a way forward, but they also highlight the challenges to be overcome if the solutions are to scale to the problem.

Year Up stands as one example. Its mission is to provide “urban young adults with the skills, experience, and support that will empower them to reach their potential through professional careers and higher education…through a high support, high expectation model that combines marketable job skills, stipends, internships and college credits.” Since its launch in 2000, it has had 15,500 students move through its programs and is currently serving 4,700 in multiple sites across the country.

Their combination of intense classroom work, close ties to local public schools and community colleges, and linkages to employers has proven successful. According to the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “More than 70 percent of Year Up graduates land jobs within four months, with starting salaries of $34,000 to $50,000, depending on the job and local market.”

A federally funded evaluation of Year Up…tracked more than 1,600 Year Up students in 2013 and 2014 and 875 similar young people who met the standards for admission but did not go through the program. The earnings of Year Up students were 53 percent more than the control group’s a year after graduation and remained far higher for the following year.

A similar effort is West Virginia’s NewForce, a partnership formed between two nonprofits to take on the challenge of helping former coal miners become tech workers. According to a Fast Company profile, it “aims to completely eradicate the barrier to entry for a career in tech, especially as so much of the talent pool may be people who previously worked as miners, and now find themselves having to start over in their careers.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

NewForce will train around 15–25 students, tuition-free, in software development and coding. All NewForce’s partner organizations will share the cost of the program so it doesn’t fall on the students.… For their employment partners, NewForce is providing a service in the form of that pipeline of talent they need to grow in the state.

The approaches of programs like Year Up and NewForce work for those whom they now serve, but how much can they grow? One limiting factor is that current students have the motivation to participate in an intense, demanding year-long program, and no one knows how many of those there are. Gerald Chertavian, founder and CEO of Year Up, recognizes the current population may not be representative. “It is a self-selecting group,” he says. “We’re asking these young people to go on a challenging journey in a high-support, high-expectations environment. It’s not for everybody.” Can these programs be augmented to bring in those who aren’t currently ready to get off the sidelines?

Scaling up will often present problems of its own. Are there enough trainers, counselors, and job developers ready to step in? Is there funding to fuel the growth of a program that might need more than $20,000 to serve each new student? Can the mission, vision, and adaptability that marks organizations like Year Up be maintained as they become larger and more complex?

Another thing these sorts of programs need are employers willing to change hiring standards to make room for those not coming out of college programs with traditional degrees. This may mean creating pipelines to teach those with non-traditional credentials the soft skills needed to fit into the culture of technical jobs. With unemployment at record low levels, there may be motivation to take on this challenge.

Lastly, some take the stance that the idea that tech work can replace jobs now fading away is not realistic. Hal Salzman, a professor at the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, told the Times-Dispatch he doesn’t see tech jobs creating a “substantial middle class” anytime soon. His calculations “show 70 percent growth in information technology jobs over 15 years, to 4.7 million in 2018. But that total is far fewer than the 12.8 million in manufacturing, a sector that shed 1.5 million jobs over that span.”

Like we said earlier, it’s complicated. Maybe it makes more sense to replicate the model or intention through supply chains that can adapt to local realities and create innovations along the way. This approach is not as centralized, of course, but brings together various players as a community of interest and intention.—Martin Levine