Cooperatives are great. We need them—especially worker-owned ones, which allow us to own the means of production and make decisions for ourselves. Hopefully, they also allow us to feel less alienated from one another, from our labor, and from sustaining our lives and livelihoods.

Yet might worker cooperatives deepen their effectiveness by using a relational, ecological framework to inform how they are organized and make decisions? At a time marked by a growing climate crisis, this is not a trivial question.

Nor is the answer to this question obvious. After all, a worker co-op operates in the interests of its worker-owners, which may—or may not—include a prioritization of ecological concerns.

The Limits of Cooperative Principles

While cooperative principles can be widely found in African and Indigenous societies, many cooperatives find grounding in the principles that emerged from what is said to be the first modern cooperative originating in Rochdale, England, in 1844. From there, a group of representatives from different countries came together to develop the International Cooperative Alliance—holding discussions, developing key principles, and making connections toward an international cooperative movement.

Even though cooperatives are often deemed as inherently “good,” they are hardly exempt from power dynamics and relational tensions.

In 1995, the ICA fine-tuned the cooperative principles. Despite that now being nearly 30 years ago, these principles continue to inform the values of worker-owned cooperatives today and are pasted on websites and walls of cooperatives across the world. These principles are:

1. Voluntary and Open Membership

2. Democratic Member Control

3. Member Economic Participation

4. Autonomy and Independence

5. Education, Training, and Information

6. Cooperation among Cooperatives

7. Concern for Community

All great things. And even better, in 2016, ICA refined and retooled them once again, creating helpful guidance notes parsing out how each of these principles should manifest in practice. This is a necessary addendum given that even though cooperatives are often deemed as inherently “good,” they are hardly exempt from power dynamics and relational tensions. These internal relational tensions make sense, considering that most of us have been socialized into a capitalist society that encourages people to act as individuals who compete against one another. We have not had much practice cooperating.

An ecological and relational framework for worker-owned co-ops would situate the natural world … in collective conversation with [its] human ‘members’.

Cooperatives in an Ecological Context

Actual cooperation takes much more than just paying lip service to saying that we are cooperating, saying that we are concerned with community, or that we value open membership. The guidance notes get specific about what these principles mean and look like in practice. Yet, even after reading both the cooperative principles and the much more extensive guidance notes, I am left wondering if we might deepen our cooperative work by using a relational, ecological framework to inform how we organize our cooperatives and how we make decisions.

If co-op members were to do this, one key question that would arise is: How does one define a “member”? If we accept the Indigenous wisdom that we are deeply relational and interdependent with one another, then the practice of being open to “members” must include the living beings and natural systems that make cooperatives possible.

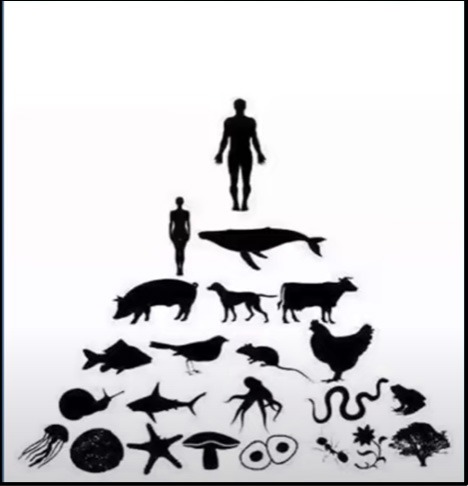

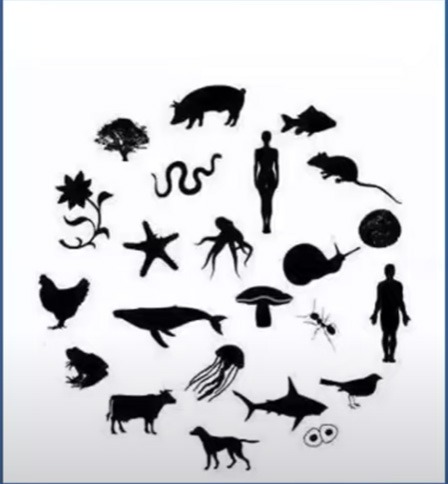

Indigenous scholar and ecologist Robin Kimmerer has a visual that can help us more fully see this. One model of the world, where humans are at the top of a pyramid, is juxtaposed against an image that sees all of life in a circle of interdependence where no being is at the top. An ecological and relational framework for worker-owned co-ops would situate the natural world—the soil, the fungi, the bacteria, the plants, the sun, the winds—in collective conversation with the human “members” of the cooperative to make truly collective decisions.

A Dispute about Tomatoes

Let me paint a picture of how a co-op might practically act on these ideas.

I am currently a member of the worker-owned cooperative farm, Riquezas del Campo, based in Hatfield, MA, on Nipmuc and Pocumtuc lands, near Northampton. During the summer of 2021, the rains poured down. Our swampy land, once the bottom of glacial Lake Hitchcock, had water pooling in puddles all along the squash field and at the edges where the land slopes down a bit, where a crawdad-like being miraculously appeared one day, as if wading along in a creek. It was late July, and we were a bit behind on tying up our tomatoes. They were already in the ground but growing taller and taller and needed somebody to help their bodies move higher and higher, instead of wider and bushier.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

One gloomy Monday evening, members of Riquezas sat around the wash station discussing which method was best for tying up the tomatoes. Our field manager, a lifelong farmer from Costa Rica, had already begun installing an elaborate post and wire system that he uses at his homestead in Williamsburg, MA. This system requires submerging posts two to three feet into the earth, with three to four posts per row, and then running a wire from post to post that can be tightened. The tomatoes are tied from their bodies to the wire and as the tomato plants get heavier, the wire can be tightened at the ends of the posts, giving the tomatoes a bit of a face and body lift.

An option that other members of the farm were vouching for, having worked on many farms in the valley that used this method, was putting stakes in the ground every six to eight feet—a lighter and less deep method that required less physical labor. Then twine is run at multiple levels through the stakes and the tomatoes are woven within and held up as they grow with another layer of twine added when needed.

The conversation that evening went back and forth among co-op members, with varying tension in our voices and bodies. “The stakes are cheaper, but they will not last as long as the posts,” said one member. Another countered, “The posts require more upfront labor but are more durable in the long run.” A third member noted that “the posts require physical and tractor labor which only one or two people are actually capable of. If we use the stakes, more people can get working on the tomatoes.”

This meeting was not the first or the last time we would talk about how to tie up the tomatoes. That summer, we ended up doing the posts, since our field manager knew this system. Other co-op members consented to this, but consent was grudging.

As the rains poured down for weeks, farms across the region saw crop yields greatly diminish due to the warm and wet conditions. Our farm was not spared. And our thoughtful attempt to decide what was best for the tomatoes was suddenly out of our control. The tomato posts that were two feet into the ground kept being raised up—the bottom of the Glacial Lake turning back into its original state of 15,000 years ago. The land was pushing the tomato posts up and out, telling us this year we would not get many tomatoes at all. The land was chiming in with its input on the decision too.

Humbled, weeks later, we began to realize, “Oh, the land is a member of this co-op, what would it think about this decision? Would it want stakes or posts this year?” We forgot to listen to the land when making our consensual decision.

Our cooperation as human-members could be more caring, more real, more grounded, when we leave our human-centric egos at the door.

What would our co-op have done differently had we slowed down to listen to the land? We might have crouched down to smell, taste, and touch the land—using our senses and intuition to communicate, since the land doesn’t speak human languages. It would have taken more time, the sort of time that is passed down from knowing land and weather patterns for generations. Perhaps we would have had to feel the wind and consider predicted weather patterns for the season. We would have had to notice that because our land is at the bottom of a glacial lake, given the heavy rains, it would likely be too swampy to hold either stakes or posts that year. Had we been more attuned to our environment, we might have realized that if tomatoes that year were to grow at all, they might have to be bushy, and there would be fewer tomatoes to harvest.

Cooperatives and the Rights of Nature

Having been involved with various collective and cooperative projects over the past 15 years, the actual work of cooperating, which is the whole idea of a cooperative, is often muddy, sticky, muddled with varying ideas, opinions, and individual histories that have shaped us as humans who act and think in different yet overlapping ways.

Beyond just stating co-ops are good, it is important to recognize these challenges when considering how good co-ops might function. This raises many questions, such as: What is the structure? How are decisions made? How are relations among the members cultivated? How do we learn to love and trust one another despite our differences?

This moment at Riquezas—where the land was communicating with us, but we were not listening—got me wondering how our cooperation as human members could be more caring, more real, more grounded, when we leave our human-centric egos at the door and welcome the natural world around us in as members too, because they are. Without them, we wouldn’t be alive at all.

To dig deeper into ecological and relational frameworks, we can obviously turn to Indigenous communities that have long operated in this fashion. This Indigenous way of cooperating and knowing the world was erased by settlers who installed a capitalist system of development and forced us all into wage labor informed by yet another pyramid, with rich humans at the top, and the poor working humans at the bottom.

More recently, Western science is catching up to this wisdom, now “proving” that humans are part of an interdependent web of life necessary for collective survival. Yet, the logic of separation fueled by elite White men who settled in these lands still pervades in even the most radical of world-building spaces.

For example, the cooperative principles were written from a Westernized human-centric worldview. If we want cooperatives to function toward the wellbeing of all life on the planet, then we need to rethink how those principles are written, and, more importantly, how they are practiced and embodied. This requires disrupting common attachments to continually putting humans at the top of a hierarchy.

I am taking some cues here from the Rights of Nature movement, where communities are fighting and succeeding across the globe in making sure that nature has the same rights as humans—nature, that is, conceived as a living and breathing entity that supports all life in an ecosystem necessary to our collective survival. Much of this movement is geared toward ensuring nature has legal rights within state legislation, to stave off the destruction that results from mining, damming, and other projects that reject the aliveness of the earth for corporate profit.

But if you believe as I do that social mores matter as much as or more than laws, then it is important to expand this way of thinking, knowing, and being beyond legislation. What if co-op members considered nature as a member that had a say in our consensus-based decision-making process? How do we learn to listen to the living kin who are, indeed, many of the most important members of the co-op?

This is quite easy to imagine on a cooperative farm, where the land speaks loudly. But how might cooperatives learn to include land and other living beings as members if you are running a cooperative not so intensely in relation with “land” or “nature”?

A cooperative coffee shop is certainly still housed on land with histories and the coffee the customer drinks is connected to many natural beings. A co-op grocery store is housed on land with histories whose products and materials come from natural beings. In both cases, perhaps meetings would take place on the land the buildings are housed on; the land beneath your feet could be smelled, tasted, touched; histories and entanglements with other beings could be noticed, named, and brought into the space. Deciding on which products to purchase or sell and from whom or how might account for our entangled relations. For example, does it make sense to purchase coffee beans that have to get shipped across the country in a tractor trailer to get to your door? Perhaps it’s better to stay closer to home? How do you know?

Tracing these worlds requires more than just naming whose Native land you are on or saying hello to the tree on your way into the building. Knowing the natural world requires slowing down, learning to listen beyond human language, taking the time to learn about deep histories and entanglements, and decentering human narratives.

Not easy work, as capitalism forces people to rush, ignore, speak over, erase, and center our individual selves. So, how to truly practice doing this remains a critical question to ponder when seeking to advance a more just economy and a just ecological transition.