Editors’ note: This is one of four articles describing the practice of capital funding, first published in NPQ‘s blockbuster summer 2013 edition, “New Gatekeepers of Philanthropy. The first three describe capital funding from the grantmaker’s perspective; this article describes it from an organization’s point of view. (Please also read “Capital, Equity, and Looking at Nonprofits as Enterprises,” by Clara Miller; Edna McConnell Clark Foundation’s Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot: A Bold Philanthropic Innovation, by the editors; and “An interview with Nancy Roob, President of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation,” by the editors.)

How do start-ups move from infancy to the next stage? Quality programming, a strong brand, skilled leaders (lay and professional), and media presence are all critical. But an obvious, if sometimes overlooked, ingredient is major investment of philanthropic dollars. In the cases of two young educational organizations, Mechon Hadar and Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, major grants transformed and positioned them for second-stage growth. The question is, can these large investments become part of the Jewish philanthropic culture?

Mechon Hadar

Mechon Hadar was founded in 2006 to empower a generation of Jews to create and sustain vibrant, practicing, egalitarian communities of Torah learning, prayer, and service. In the first three years, Mechon Hadar’s budget grew from $240,000 to $660,000. At that level of funding, Hadar was able to launch and grow a summer fellowship from eighteen students to forty students. But Mechon Hadar was programming only eight weeks of the year and had only two full-time staff. Although the budget had more than doubled, an infusion of major philanthropic dollars was required to take the leap to the next level and offer twelve months of programming.

For Mechon Hadar, that investment came in its fourth year, in the form of four multiyear grants: a three-year signature Covenant grant ($153,000), a three-year AVI CHAI Fellowship award ($225,000), a renewable $150,000 grant from the UJA-Federation of New York, and, most significantly, a five-year $1,375,000 challenge grant from the Jim Joseph Foundation. Until that point, Mechon Hadar’s largest grant had been a one-time $190,000 grant from the Jim Joseph Foundation. Although Hadar had been supported by more than twenty national foundations in its first three years, the average grant was $25,000. The next year, that average grant size doubled, and the overall budget grew to $1.2 million.

This increase in grant support was not a coordinated effort by foundations; rather, it was a fortuitous occurrence of increased investment that allowed Mechon Hadar to take a daring programmatic leap of faith: hire faculty and staff (including a development director) to work full time; open a year-round immersive learning program; and run multiple classes, seminars, and intensives during the ten months that had previously been unprogrammed. The organization transformed significantly in the space of twelve months, and its impact grew exponentially. Now its 350 alumni live in dozens of cities across the United States, Israel, and Europe, and, according to an independent evaluation conducted by Ukeles and Associates, Inc., have impacted forty thousand of their peers using the skills, confidence, and knowledge they gained at Mechon Hadar.

Related Articles:

Edna McConnell Clark Foundation’s Growth Capital Aggregation Pilot: A Bold Philanthropic Innovation

An Interview with Nancy Roob, President of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation

Capital, Equity, and Looking at Nonprofits as Enterprises

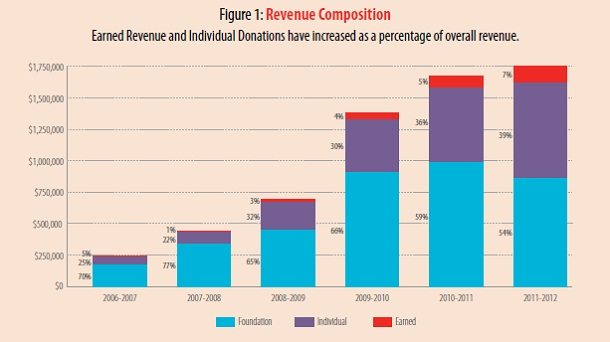

The matching grant from the Jim Joseph Foundation served as a major catalyst for Mechon Hadar to increase its individual donor base. Indeed, Mechon Hadar has managed to balance the relative investment of individual donors with institutional foundation support. While that balance used to be 70 percent foundations and 25 percent individuals (with 5 percent direct revenue), by last year that had shifted to 54 percent foundations and 39 percent individuals (with 7 percent direct revenue). But while the overall budget has increased every year, actual foundation investment decreased on a real (and not just relative) basis last year (see figure 1).

Mechon Hadar is now poised to make its next major programmatic leap. Having run its twelve-month program calendar since 2009, Mechon Hadar is now focusing on launching three centers (Jewish Leadership and Ideas; Jewish Law and Values; and Jewish Communal Music). These centers will extend well beyond the physical walls of Mechon Hadar’s New York base, and greatly increase its impact. The question is, will the same fortuitous occurrence of funding that allowed Mechon Hadar to make its first quantum leap materialize to help move the organization to the next stage?

Yeshivat Chovevei Torah

Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (YCT), the open Orthodox rabbinical school, is the realization of Rabbi Avi Weiss’s dream to shape an orthodoxy that is open to the voices of others and driven by professionally trained rabbinic leaders. Since opening its doors, in 1999, YCT has graduated nearly one hundred rabbis from its intensive four-year program, grown its annual budget from $500,000 to $3.5 million, and raised $35 million in donations. YCT’s alumni serve at the forefront of innovative congregations, inspire students in day schools and on college campuses, and lead organizations in the Jewish community’s ecosystem of grassroots engagement efforts, such as Kevah and Uri L’Tzedek. (Kevah engages Jewish identity and builds community through the study of classical Jewish texts; Uri L’Tzedek is an Orthodoz social justice organization guided by Torah values and dedicated to combating suffering and oppression.)

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

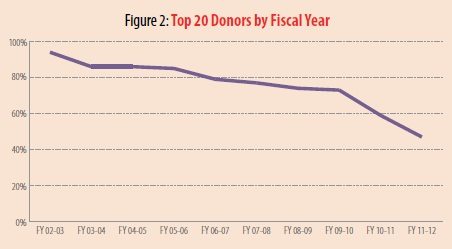

Early support for YCT was offered by a close circle of friends and supporters who believed in Rabbi Weiss’s vision. In the yeshiva’s first years, the tip twenty donors carried well over 85 percent of the institution’s budget. As the yeshiva built its donor base, by 2007 support from these angel donors dropped to a rate nearing 70 percent of the yeashiva’s overall fundraising (see figure 2).

While angel donors were critical to YCT in its start-up phase, in the long term the financial model the yeshiva in a precarious position, threatening its sustainability and long-term viability. Over time, founding donors tire, and reliance on a limited number of insecure revenue streams constrained the yeshiva’s ability to expand programming and form long-term plans.

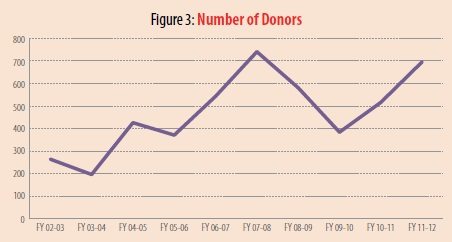

A similar analysis may be drawn from the number of individual donors giving to the yeshiva. The number of donors grew steadily in the yeshiva’s early years, with the number of donors in 2007 nearly triple the number who had given in 2002. Such a growth pattern put YCT on the fast track to greater stability and sustainability. With the onset of the financial crisis in 2007, however, the number of donors dropped precipitously, forcing YCT to rely again on its base of angel donors (see figure 3).

In early 2011, the Jim Joseph Foundation awarded Yeshivat Chovevei Torah a five-year $3 million grant for organizational capacity building. As a cornerstone of this grant, $2.5 million was designated as a challenge grant, matching dollar-for-dollar donations from new donors, recaptured donors, and increased gifts. With the assistance of this gift, YCT was able to meet the challenge in slightly over two years and raise more than $1 million from 390 new donors; $0.3 million from 200 recaptured donors (those who had not given since FY 2008–09); and nearly $2 million in increased gifts from 195 current donors. Most profoundly, by building its base of support, the percentage of YCT’s annual fundraising derived from the top twenty donors dropped significantly, to nearly 40 percent in 2011–12, and the number of donors rose again to pre-recession levels.

With angel donor support still critical to the yeshiva’s operations, but at a more sustainable level, and the total number of donors on the rise, YCT is in a position to enter the next phase of its institutional journey. Catalyzed by support from the Jim Joseph Foundation and strengthened by a broad base of donor giving, in September 2012 YCT announced that Rabbi Avi Weiss would step down as president of the Yeshiva, and Rabbi Asher Lopatin would take up the reins of the institution. This leadership transition marks a new stage in YCT’s institutional growth, and affords an oppor- tunity to reflect on the past and develop new plans for the future.

Notwithstanding the broadened base of support, the leadership transition is not without financial challenges for YCT. Many of the angel donors who have sustained YCT for over a decade did so (at least initially) out of love for and devotion to Rabbi Weiss. Thus, in addition to a transition in leadership, the yeshiva is planning for the possibility of a transition in donors. Similarly, while YCT is extremely fortunate to have completed the five-year match in a little over two years, the timing is difficult, as it deprives Rabbi Lopatin of an important tool in attracting new donors. In planning for the transition, significant consideration was given to maintaining the support of existing donors while continuing to diversify and expand the institution’s donor base.

***

The lessons here are clear: two start-ups that had proven themselves in their early years were prime candidates for relatively large investments. Both parlayed those dollars into a dramatic increase in programming, impact, and organizational sustainability. The percentage of individual donors versus overall funding is on the rise for both Mechon Hadar and YCT, leading to a more balanced funding portfolio.

We believe that there are many organizations that could benefit from large investment—some new start-ups looking to advance to the next stage, and others who have already made it to the next stage, like Mechon Hadar and YCT. These organizations will thrive or fail depending on whether they find second- and third-stage support. Jewish organizations need to find and share their visions of vitality and expansion. And Jewish funders need to be open to devoting more resources to looking for opportunities in which taking a chance on an organization with thoughtful plans for growth could yield big returns for that organization and the larger Jewish community. Equally as important, those organizations could become the agents through which foundations achieve their goals.