June 18, 2018; Columbia Journalism Review

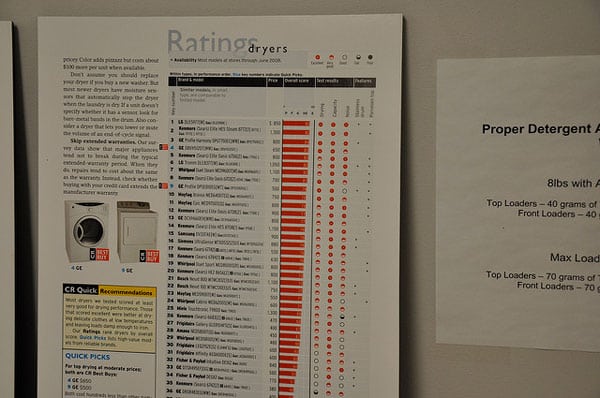

In an age in which print subscriptions are increasingly rare, Consumer Reports remains a giant. As Karen Ho writes in the Columbia Journalism Review, “Consumer Reports is unusual in the American media industry for its nonprofit subscription business model, massive resources, and dedication to original reporting and research.” Its scale is impressive. The magazine “still produces 12 print issues a year, including one focused exclusively on cars, as well as an annual buying guide. In 2017, CR had 3.6 million print subscribers (more than People), who pay $30 a year, and 2.9 million online subscribers. Its online traffic in 2017 was 14 million unique visitors, up 17 percent from the previous year.”

One unique feature of Consumer Reports is that it has never accepted a single advertising dollar, according to CEO Marta Tellado. But, Ho observes, income “is down, subscriptions are falling, and the 83-year-old magazine faces an ever-growing assortment of advertising-driven and online-only competitors, including the Wirecutter, a site owned by the New York Times.” Consumers Union, notes Ho, “began in February 1936, after a group of striking employees at its predecessor, Consumers’ Research, were frustrated with working conditions.”

In addition, Ho observes, Consumer Reports covers “larger issues like discrimination in the car insurance industry, food recalls, scams after natural disasters, net neutrality, and the Equifax data breach.” It is also engaged in “a multi-year strategy focused on attracting younger readers, primarily through its digital content both in and out of its paywall.” Further, Consumer Union does advocacy work on behalf of consumers.

Consumer Reports has always prided itself on its independence, which is why it refuses ads. It also insists on buying all test products at retail prices. In fiscal-year 2016, which ended May 31, 2017, that meant that the magazine spent $2.1 million on cars and $1.5 million on all other consumer items. The magazine also employs 550 staff—comprising engineers, statisticians, mechanics, lawyers, and its editorial team—plus the operating costs of the company’s 50 testing labs, its 327-acre auto test center, three other offices, fundraising, lobbying, and, of course, its own advertising. In its most recent financial statements, the magazine “reported expenses totaling just under $247.2 million for the fiscal year and revenues of more than $241.7 million.”

Finances have been complicated. The organization lost 13 percent of its staff in 2012 and 2013. According to its latest financial statement, Ho observes, “revenue from subscriptions, newsstands, and other sales has steadily fallen from $234.2 million in the fiscal year ending on May 31, 2013, to just under $205.5 million in 2017, a decline of more than 13 percent. Operating income also fell significantly, from $8.2 million in 2015 to a loss of $5.9 million in 2016.” Last year was slightly better, with a loss of $5.4 million.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Subscriptions are also falling. In 2007, Consumer Reports had an astonishing 8.5 million subscribers. In short, its 3.6 million print subscribers, though huge, marks a major decline. Subscription revenues have fallen more than $31.8 million between June 2014 and May 2017.

According to Chief Financial Officer Eric Wayne, the organization’s financial reserves remain at $167 million as of May 31, 2017. This gives Consumer Union considerable cushion, but losses can only go on so long. Another challenge, notes Ho, is an aging readership. In 2008, the average print subscriber was 60 and the average online subscriber 50. “By 2016,” Ho remarks, “those ages had risen to 65 and 56, respectively.”

As Ho observes, Consumer Reports is very visible, producing “its own multimedia content, including podcasts and 360-degree video, for a network of 150 local broadcast and Telemundo stations. This digital content is then published or syndicated on its website, Amazon, Apple TV, MSN.com’s auto vertical, and on its YouTube channel.”

Again, though, unlike, say, Car and Driver, Consumer Union does not allow “its ratings or review” to be used in advertisements. Jennifer Stockburger, Consumer Union’s director of operations, notes that car manufacturers pay publications up to $300,000 for the right to advertise their ratings. As to whether Consumer Union might follow, “We’d be fools not to think about it,” Stockburger says. But a spokesperson notes that the publication has not done so to date because it does not want to “jeopardize or conflict with our mission and our core values.”

The cost, as illustrated by the experience of the United Way, of getting this wrong and deviating from core values is not lost on Consumer Union staff. As Tellado puts it, “In a sea of unaccountable review sites and user comments, Consumer Reports offers something unique: independent, nonprofit insights that equip people to shape the marketplace and navigate day-to-day purchase decisions. Because we buy every product we rate and don’t sell ads, people know that we serve one constituency and one constituency alone: consumers themselves.”—Steve Dubb

Disclosure: Chuck Bell, Chair of the Nonprofit Quarterly’s board of directors, works as a consumer advocate for Consumers Union, the policy division of Consumer Reports.