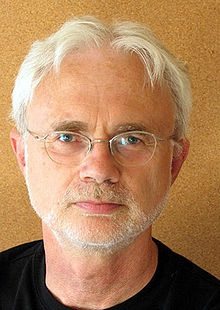

John Adams, 1947 – Credit: Peter Stevens

October 20, 2014; Daily Forward

On Monday, the New York Metropolitan Opera’s opening night performance of The Death of Klinghoffer was greeted by several disruptions from hecklers inside the opera house, hundreds of placard waving protesters outside, and thunderous applause for the work’s composer, John Adams, as the curtain fell. The work, commissioned by American and European opera companies, has been a lightning rod for controversy beginning before its first performances in 1991.

Prior to the opera’s American debut at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Lisa Klinghoffer and Ilsa Klinghoffer, the daughters of Leon and Marilyn Klinghoffer, expressed their strong displeasure with the opera: “We are outraged at the exploitation of our parents and the coldblooded murder of our father as the centerpiece of a production that appears to us to be anti-Semitic.” Lynn Schusterman, founder and co-chair of the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, depicts the work as “an opera that presents a singular viewpoint about a horrific act of terrorism, contains language that can only be described as anti-Semitic and goes so far as to imply moral equivalence between the Nazis and Jews.”

Supporters of the opera have responded to these charges. Michaela Martens, the performer who portrays Mrs. Klinghoffer in the Met’s staging, said:

“I don’t think that Leon Klinghoffer’s death is something that should be forgotten, and it’s not pleasant to revisit it, and yet I think his death should not have been in vain. When this opera comes up every two or three years, this discussion needs to happen. This man died a horrific death, and we need to remember this person. At the end of the opera, the whole audience is sobbing. You cry for the Klinghoffers, you cry for the whole situation. The opera gives us permission to grieve.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A decade earlier, commenting on the same opera, art critic John Rockwell said that Klinghoffer “shows unequivocally that murder is nothing more than that, vicious and unconscionable.”

The arts have the power to engage audiences on multiple levels; they can foster consideration of difficult issues. In his review of the opening, New York Times opera critic Anthony Tommasini captured a quantum of the power of the medium: “Of all the arts, opera can use the subliminal power of music to explore motivations, including seething hatreds.”

But should publically supported arts organizations like the Metropolitan Opera use this power? Are there issues and perspectives that should be kept off the stage? This is the important question that Klinghoffer puts before us.

First Amendment expert Floyd Abrams wrote in October 2014 that, though no First Amendment issues were raised, he opposed the staging of this opera. “The killers…chose to commit their crime. So did Lee Harvey Oswald, James Earl Ray and Osama bin Laden. We can expect no arias to be sung in their defense at the Metropolitan Opera, and there is no justification for any to be sung for the Klinghoffer killers.”

Oskar Eustis, the artistic director of the Public Theater, held the opposite view. “It is not only permissible for the Met to do this piece—it’s required for the Met to do the piece. It is a powerful and important opera.” According to the general manager of the Met, Peter Gelb, “Somebody who looks at this objectively understands that all the opera does is try to explain the motives of the terrorists so that we understand the terrible crimes they committed.”

The positive impact that can come from controversial works is illustrated by a staging of Klinghoffer in St. Louis and the community dialogue that it fostered. Speaking of her experience stimulated by the opera’s staging in St. Louis, Rabbi Susan Talve recently said, “They’re missing an opportunity for dialogue in New York. If they won’t even talk about it there, they’re missing an opportunity to grow, to make connections with people that have different ideas. That’s what happened here.”—Marty Levine