July 18, 2019; The Intercept

California’s gig economy is being roiled by proposed legislation—AB 5—which would write into law clear standards as to when workers can be classified as “independent contractors.” The law is based on a 2018 California Supreme Court Decision, Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court of Los Angeles.

As NPQ noted last year when the Dynamex decision was published, “In a decision that has been called a contractor apocalypse, an earthquake, and a seismic shift, the California Supreme Court significantly tightened independent contractor rules. In a 7–0 ruling, the California Supreme Court ruled, in essence, that if it looks like an employment relationship, it is.”

Companies operating in California have been trying to avoid the implications of that 7-0 ruling ever since.

In Dynamex, the court laid out a three-part test for whether a worker qualifies as a contractor. The worker must be:

- Free from control of the entity paying his or her wages;

- Doing work that is outside the usual course of business of the employer; and

- Engaged in an independently established business.

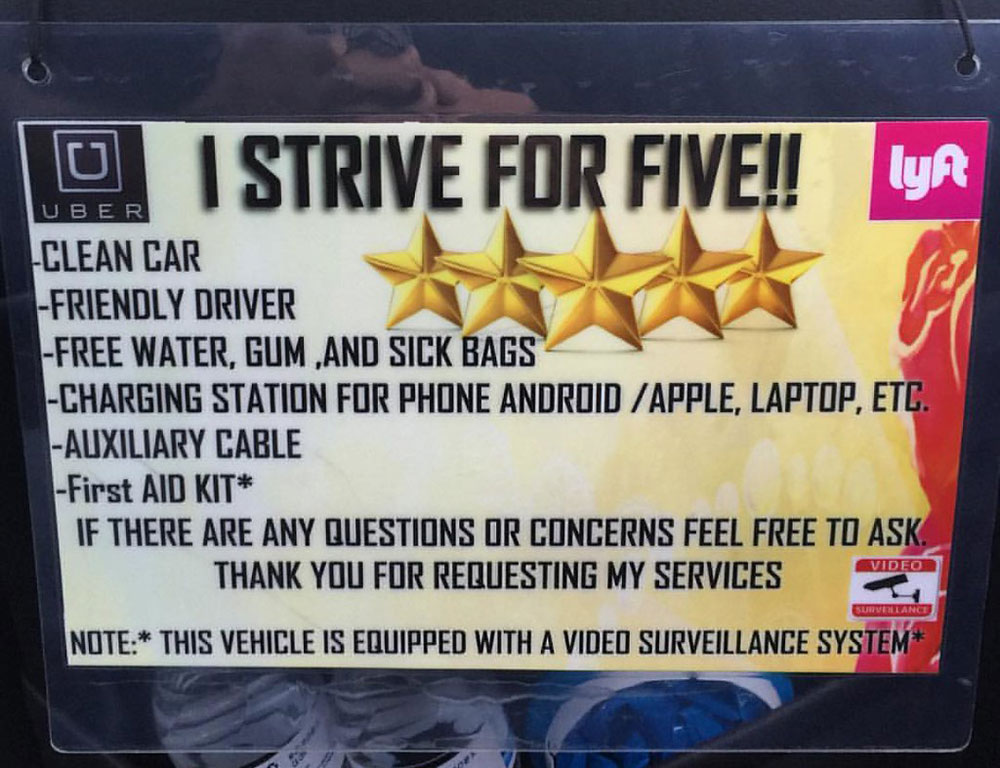

This definition applies to traditional companies as well as platform companies like Uber and Lyft, but it is the latter who would see their business model upended the most.

Thus far, many California employers, including Uber and Lyft, are not complying with the Dynamex decision. Uber and Lyft in particular are seeking a “compromise” that would either exempt them from AB 5 entirely or amend the bill to accommodate their business models.

According to Lawrence Katz of Harvard and Alan Krueger of Princeton, as of 2015, 8.4 percent of Americans—or roughly 12.5 million people—work as independent contractors, up from 10.3 million in 2005. Regionally, the numbers can be even greater and “gig economy” companies like Uber and Lyft can be a significant share of this. For example, if Uber had employees, it would be New York City’s largest private-sector employer, according to a recent analysis from the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission. Uber and Lyft’s biggest market is California, so what happens with AB 5 matters.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

It also matters to the state. The state estimates it loses $7 billion in payroll tax annually due to companies misclassifying employees as independent contractors.

But the biggest losers are the workers themselves. In a recent paper, the National Employment Law Project (NELP) laid out the ways in which US labor regulations confer protections on employees. Independent contractors are assured none of these:

- Right to organize and bargain collectively

- Minimum wage and overtime protections

- Access to unemployment insurance

- Access to workers’ compensation

- Employer contributions to Social Security or retirement

- Anti-harassment and discrimination protections.

NELP argues that the platform companies are drawing on an old playbook to limit the rights of workers. In a recent op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, David Weil, who led the US Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour Division during the Obama administration, similarly argued that the ride-hail companies are misclassifying workers. While he acknowledged that some companies have employment situations that are ambiguous, he wrote, “Uber and Lyft are not among those close, gray area cases.” (Weil’s opinion, it should be noted, has been rejected by the National Labor Relations Board, headed by Trump-appointed General Counsel Peter Robb, which recently issued an opinion that Uber workers are not employees.)

Uber, Lyft, and other platform companies such as Handy, which provides home services, have based their argument for “non-traditional” employment on the fact that their workers have flexibility in choosing when to work. Arguing that flexibility is important to their workers, they say employee status would force them to make significant changes—for example, organizing labor into shifts. But as the National Employment Law Project points out, “Laws don’t force workers into choosing between having basic workplace protections and having flexibility; companies do.” Platform companies are falsely using “flexibility” for workers to fight to maintain a business model that exploits labor and delivers enormous profits.

Many ride-hail drivers are not happy with their lot. In May, as reported in NPQ, thousands of Uber, Lyft, and Juno drivers held a one-day walkout to protest diminishing earnings and poor working conditions. The average wage for Uber drivers, Steve Dubb reports, is $14.73 per hour, about $30,000 for a full-time worker. Additionally, gig workers are coming together to press for better wages and benefits through groups like Gig Workers Rising.

Two labor unions, SEIU and the Teamsters, are leading the fight for AB 5 in California, but some worry that the unions will negotiate a backroom deal with Uber and Lyft that exempts ride-hail drivers from many of the protections the Dynamex decision promises. The fears seem well-founded, according to the Intercept. In an interview with California Labor Federation spokesperson Steve Smith, he suggested “that unions may be open to alternative paths for drivers of ride-hailing apps specifically.” A compromise could include a way for unions to organize workers as well as a benefit fund to which employers would contribute but would exempt these workers from AB 5 regulations.

Right before his recent death, Hector Figueroa, then-president of SEIU 32BJ in New York, warned of such a compromise. In a New York Daily News op-ed, according to the Intercept, he criticized “his state’s labor federation for backing a bill that would let unions collect dues from gig workers without giving those workers full rights as employees.” Wrote Figueroa, along with co-author Bhairavi Desai, the NY proposal is a “giveaway to gig companies,” as would be a similar deal in California.—Karen Kahn