In 2020, iF, A Foundation for Radical Possibility (then the Consumer Health Foundation) hosted a retreat with our board and staff. At that retreat, we conducted a racial equity versus racial justice Verzuz-style battle to clarify which would be our focus moving forward, asking ourselves, “What do Black people need to heal?”

We concluded that Black people need racial justice—an acknowledgment of the intentional harm done to a collective people. Along with that acknowledgment, we believe there is also a duty and obligation to repair. Only then can we get to a place of healing.

As an organization, we decided to take a stance in support of reparations for Black people, formally acknowledging the debt Black people are owed from our government and public institutions. However, to truly be in solidarity with Black people, we realized that as a private foundation, we needed to look in the mirror as well. With our roots in racialized capitalism, philanthropy should also be called to account.

What if we investigated the wealth origin of philanthropy in our region?

What if we investigated the wealth origin of philanthropy in our region? What if the wealth that created our endowment was extracted from Black genius, labor, and land, and should therefore be committed to fund repair?

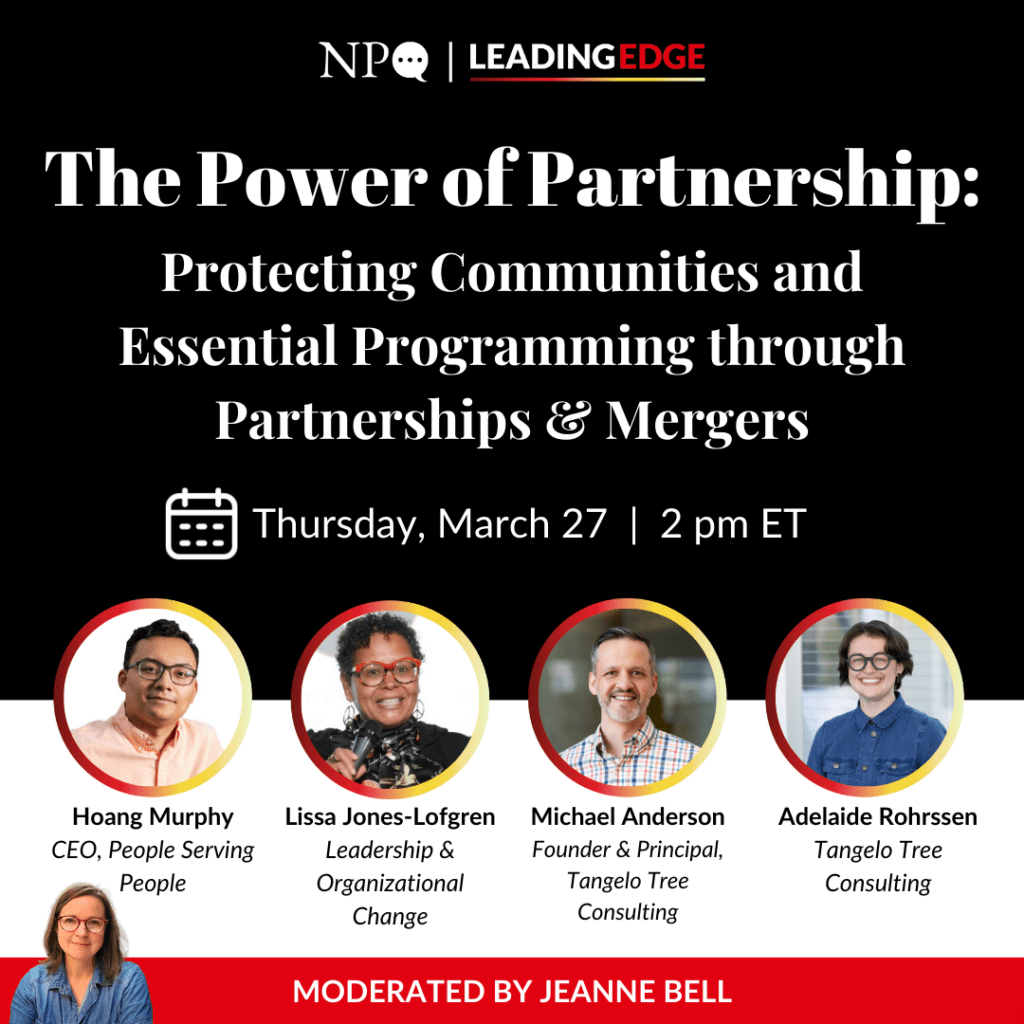

In our search for a credible, independent partner to lead this research, we decided on the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). We met with NCRP to propose our idea for the study. They agreed.

Designing the Study

Originally, iF planned to do this work collectively and collaboratively with other funders. How strong and impactful would it be for multiple foundations to embark on this journey of redress and repair together? Between 2021 and 2022, we spent a year in conversations with foundation leaders in our region who had explicit commitments to racial equity or racial justice, inviting them to partner with us on this project.

They all said, “No.”

While everyone we spoke with acknowledged the importance of history, reasons given to not engage included optics, fear that anything negative uncovered about their wealth origin may harm their philanthropic activities; timing; being too busy with other projects; and lack of confidence that a philanthropy-serving organization would adequately scrutinize philanthropy.

After a year of conversations, we decided to move forward without foundation partners and funded the entire project ourselves, to the tune of $500,000. By the beginning of 2023, NCRP had selected eight foundations they would research in this pilot study. In January 2024, Cracks in the Foundations: Philanthropy’s Role in Reparations for Black People in the DMV was released.

Cracks in the Foundation draws on both quantitative and qualitative research from publicly available information to shine a light on the ways Black people have been exploited to build philanthropic wealth. The report focuses on four specific sectors that have caused past harm to Black people and their communities—the media, housing, employment, and healthcare. The study also offers case studies of eight foundations in the DC region, including iF, that are illustrative of that harm.

Informed by an advisory group of community leaders and local academics, the report also establishes a Reparative Framework for Philanthropy and offers five recommended actions for foundations seeking to address past harms: reckon, connect, repair, decolonize, and advocate.

Our hope remains that this report will encourage other foundations to engage in their own process of redress and repair, seed collaborations, and, when needed, compel sector stakeholders to hold up a mirror and address the “cracks in our foundation,” both individually and as a sector.

How the Field’s Responses Are Informing Our Work

The reactions we have received about the report, both before and after it was published, have varied significantly.

The reactions we have received about the report, both before and after it was published, have varied significantly across foundations, individuals within them, nonprofit and government leaders, and others. These range from supportive to constructive to defensive to negative to silent—with combinations and nuance within each category. We offer examples of each response below.

- Supportive: Many have expressed directly to us that this type of truthful and critical examination of philanthropy is overdue, that the report makes a strong case for why and how philanthropy must reckon with its wealth origins, and that they are thinking about how to make the case within their institutions to engage in a process of reckoning and repair. Several allies have also acknowledged that iF has taken on multiple risks through this work and asked how they could flank us as we are out in the world talking about it.

We need this support. We are thankful for this support.

Let’s move from words to action! We want to champion those who are bravely making the case in the sector, within their own institutions, and even within their own families to reckon and repair. We can do this in solidarity, through critical friendship, and with love.

- Constructive: Some people have shared with us their feeling that the report is too easy on the foundations and wealth generators studied. For instance, the case studies of the eight foundations were “buried” in the appendix, or the report gives the individual wealth generators too much of a pass for being caught up in systems and structures and not holding them accountable for intentional, individual actions from which they significantly profited.

We do not disagree with these critiques. At the same time, we understand why NCRP made these choices, and we support them. History and the lived experience of so many have proven that when people in power feel threatened, Black people get hurt.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In fact, Black people have already gotten hurt, including losing jobs, because of the report. As a field, we need to develop strategies to avoid the perpetuation of Black harm.

- Defensive: Many have criticized that the report focuses on the past rather than the present and future. Comments of this ilk often come from people who want to uplift the grantmaking their foundations have done to support Black people. Or they feel a need to defend their founder and all the good things he did for Black people. We are reminded of the quote by Haruki Murakami, “What we call the present is given shape by an accumulation of the past.” In short, to have a more just present and future requires addressing the harms of the past.

Grantmaking is not reparations. Moreover, given the Black funding gap, philanthropy has not adequately addressed the needs of Black communities, let alone repair the harm the sector has caused.

Defensiveness is often connected to denial, and denial is a stage of grief. We respect that people may need to work through all the stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—before they are ready to engage in a process of reckoning and repair. The task here is to encourage them to do that and ensure that more harm to Black people does not happen while they are working through it.

- Negative: Negative feedback shared directly with us has come from some of the foundations studied for the report. This has included questioning our integrity and trustworthiness because we did not ask people for permission to be studied (though they were selected by NCRP). Some have insinuated that we have an axe to grind. We’ve also heard there’s an undercurrent of negative reactions regarding our foundation and others in philanthropy doing so much grantmaking that benefits Black people now, and that should be enough. We even heard people referring to us as “mean.”

To be honest, this is offensive. We made significant efforts to invite other foundations to partner with us on this research, and they declined. We have no axe to grind. We are not looking for retribution. We are seeking justice.

Truth-telling has to be a part of the sector’s professed commitment to transparency and accountability. We want to focus on moving those who are passionate and willing. We do not have the resources—financial, logistical, or emotional—to convince hostile people to see the light. That said, so long as people are willing to engage with us respectfully in this conversation, we are willing to engage as well.

- Silent: Silence is the most troubling response we have received. Some foundations studied stopped communicating with us during this process or never responded at all. We’ve also heard from some foundation colleagues that though there might be many informal conversations about the report taking place among staff in their institutions, they have had no formal conversations with executive and/or board leadership.

Why is this silence so troubling? Some foundations likely do not feel like they need to engage in a process of reckoning or repair—because they believe they have done nothing wrong or that any wrongs they have done are made up for all the good done since. This lack of awareness and accountability for past actions might also apply to current actions. What harm are these foundations continuing to perpetuate against communities, grantee partners, and their own people?

We need brave foundation trustees to move their colleagues into discussion and action. So many foundation leaders and staff we speak with say that their boards are impediments to real action that advances racial justice. We need to both hold boards to account and support them on their journey. Additionally, we need to support Black foundation leaders and staff who have been beaten down by constant case-making for the humanity and deservedness of repair of their community.

While we are disappointed by the negativity, defensiveness, and silence that we have seen, we are not surprised. Philanthropy has long prided itself on its “goodness.” Holding philanthropy to account for its harmful origins often triggers an existential crisis for the sector and the people in it. There was even one foundation studied that, amid the report being finalized and our efforts to engage with them, made the decision to pause operations indefinitely.

[Our own] wealth origin story, however, was contrary to what we believed.

Our Own Reckoning

But what about us?

We have long taken pride in what we believed were our racial equity roots as a health conversion foundation endowed by the sale of the Group Health Association (GHA).

But the story proved to be more complicated. It turns out that when GHA started in the 1930s, it allowed only White members. It was only after the group faced financial instability and needed more revenue that it allowed Black people to join.

In hindsight, this makes sense. We know that the healthcare system was segregated in the 1930s. This wealth origin story, however, was contrary to what we believed. We struggled when NCRP first shared this information with us. Now that we know this truth, we cannot unknow it. We are committed to reckoning with it.

Our foundation has made intentional efforts to decolonize our institution. This has included ensuring that community members have decision-making power by writing into our bylaws how they should be engaged in the grantmaking and governance of the foundation. With regard to our endowment, we deleted “in perpetuity” from our bylaws and increased payout well above 5 percent, shifted to mission-aligned investments, and hired BIPOC investment advisors. In addition to all this internal work, we also very actively and publicly advocate for local and federal reparations.

The Struggle Continues

Now that we’ve learned the truth about our wealth origin, we are starting to reckon, connect, and repair. We kicked off our redress and repair process this past May during our 2024 board and staff retreat.

Our approach will be multi-phased: Phase One will initially be internal and focused on additional research needed to answer the question: Who do we owe? Phase Two will be direct engagement with the harmed communities to transparently co-create the answer to the question: What do we owe them? Phase Three will be the payment of a debt owed, which might involve direct reparations.

Given all this, will we keep pushing for philanthropy to hold a mirror up to itself?

Again and again, we say, “Yes.”