“We [are] creating space where we can see what we can do together.”

—Sarita Gupta, co-director of Caring Across Generations and executive director of Jobs With Justice

The Management Assistance Group (MAG) is one of NPQ’s go-to sources of information about social justice movements. MAG works with a number of the networks that are moving some of this nation’s most difficult issues. MAG has come to believe there are five elements that are critical to advancing a thriving justice ecosystem. This is the second in a special five-part series, in which MAG and NPQ invite you to contribute to the evolution of what these elements mean in practice. Let’s start something!

Leadership in a Broader Ecosystem

A critical shift is happening across the social sector. More of our partners are expanding their focus of attention from single organizations, to coalitions, to movement networks oriented around a shared vision and values. We’re seeing people commit both to strategies—structures and behaviors that nurture movements over the long term—and to forging the relationships needed across issue areas and sectors to address complex challenges. This shift from competition to collaboration, from single issues to intersectionality, from equality and fairness to equity and justice, and from scarcity to collective abundance requires different ways of imagining and living into leadership.

This shift is similar to our evolving understanding of the lives of trees, thanks in part to Peter Wohlleben’s book, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries From a Secret World. Sally McGrane, a journalist writing for the New York Times, recounts how Wohlleben, a German forest ranger, describes trees in the forest as social beings.

They can count, learn and remember; nurse sick neighbors; warn each other of danger by sending electrical signals across a fungal network known as the “Wood Wide Web”; and, for reasons unknown, keep the ancient stumps of long-felled companions alive for centuries by feeding them a sugar solution through their roots.

Not only are trees social beings with highly interconnected lives, but their health and, thus, that of the entire forest is dependent on this mutuality, this focused attention on each other’s well-being. Similarly, leadership is not a codified set of structures, practices, people, or even a fixed state. Leadership is the capacity to create something of meaning and align values and actions across groups of people or communities. It is about relationships among people and how they support, complement, and supplement each other and the broader ecosystem.

As one of the authors, Vincent Pan, has been known to say, “In order for movements to succeed, we have to de-center, grow, and redistribute leadership. We need to see our organizations and ourselves in a different way.” (Network Leadership Innovation Lab Evaluation Report, by Rachel Rosner and Madeline Wander, May 2015.)

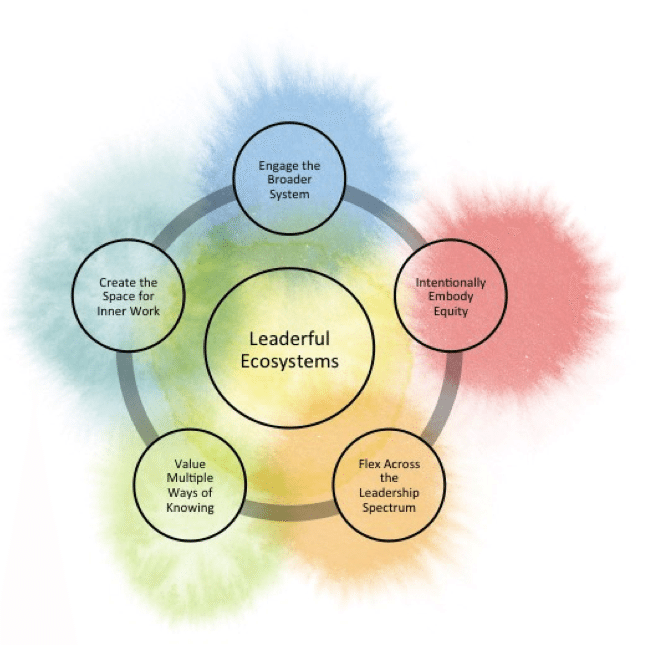

In order to grow leadership from this highly interconnected place, we need the nourishment of the five key nutrients of leaderful ecosystems.

- Leadership engages the broader system and networks of leaders within it.

- Leaderful ecosystems intentionally build relationships to embody equity.

- Leadership is flexible—sometimes more directive and other times more collaborative.

- Leadership values multiple ways of knowing and the wisdom of and contribution from multiple voices and perspectives.

- Leaders create the space for inner work that is needed for transformation.

Engaging the Broader System

Joseph Castro, president of California State University (CSU), Fresno, finds it critical to think of leadership within an interconnected system. CSU Fresno is part of a broader ecosystem, one that is larger than its students, staff, and faculty. It is part of the social and economic fabric of Fresno and its surrounding communities.

“I think of myself as working with all members of a community,” Castro says. “While I may have more influence over university policies, I see leadership as a highly collaborative practice.”

For Castro, engaging the system requires deep listening in order to see challenges from a variety of perspectives. “Oftentimes, I’ll be asked to make a rush decision about something based on a limited point of view. Unless it is an emergency, I try never to do this. I make sure to pause, to listen and consider multiple points of view. When I look again at the situation, it looks very different.”

Castro has found that the more positional power he holds the more critical it is to listen and engage others in defining both the problem and solution. “It’s a humbling process,” he says. “But it leads to better outcomes every time.”

By engaging in deep conversations with communities like Kerman, a small town about 20 miles west of Fresno, Castro learned that the university’s programmatic emphasis wasn’t meeting the needs of the community. At the time, there were 270 students from Kerman attending CSU Fresno (nearly 20 percent of the entire 18- to 24-year-old population) and almost all of them were the first members of their families to go to college. The ripple effect of this can be profound. Notes Castro, “When one sibling goes to college, other siblings tend to follow.” Additionally, students from Kerman and other smaller towns in the Central Valley tended to return home after college, so the graduates are part of the economic and social growth of their communities. And, in turn, the health of the communities and its members are part of the health of the university. By grounding his efforts in an understanding of the ecosystem, Castro was able to share the university’s efforts and draw on the knowledge of the local community to identify ways of even more effectively meeting Kerman’s needs for more teachers, engineers, and health care practitioners.

Despite the institutional forces that expect, even demand, older versions of leadership—those that are egocentric, organization-centric, or heroic—Castro is building the early foundations of shared leadership. As he says, this leaderful ecosystem is “rooted in real engagement and inclusivity.” It is a practice that will ensure the entire ecosystem, the forest of interdependence and necessary mutuality, can thrive.

Explicitly articulating how we exist as a part of a broader ecosystem is necessary because so much nonprofit thinking has focused on issues of organization-centric management and effectiveness at the expense of attention to broader community leadership and systemic change. We have also seen how funding dynamics fuel unhelpful competition that can accentuate borders between organizations, especially those whose cooperation might benefit social movements the most.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Intentionally Building Relationships to Embody Equity

Leaderful ecosystems that embody equity need people, structures, and cultures that allow us to nurture one another’s leadership. At Chinese for Affirmative Action, for example, it has long been recognized that achieving aspirations for multiracial democracy and social justice is going to require bringing many more people into the work and into leadership roles that go beyond any one organization. As one intervention, several years ago Chinese for Affirmative Action made a core commitment to leverage assets to create space and a home base for progressive Asian Americans, which evolved into Asian Americans for Civil Rights and Equality (AACRE). The AACRE network now consists of nine social justice groups organizing on a range of issues including immigrant rights, LGBTQ inclusion, combatting anti-Muslim hate, and reversing mass incarceration. The network allows for more equitable sharing of resources and the exchange of ideas in service of shared values. This works to cultivate a more leaderful ecosystem across organizations in all areas of advocacy, especially for those who are currently rendered invisible or marginalized by dominant structures.

Many of the authors’ partners are similarly shifting from traditional models of leadership development to more leaderful models. For Katherin Canton, co-director of Emerging Arts Professionals (EAP) San Francisco/Bay Area, being leaderful means focusing on relationships and equity.

When we aren’t cultivating deep relationships with people…we aren’t serving our mission. We have all participated in systems that exploit us and each other; [ones that] focused on instant gratification. The individualistic, ego- and organization-centric frame, with its nearly exclusive focus on results doesn’t honor the whole person and, thus, doesn’t allow oneself or others to emerge.

For Canton and her collaborators at EAP, there’s one key principle to cultivating a leaderful ecosystem: Stop thinking about people in terms of the services they provide or the transaction they are enabling to taking place. “I focus on seeing people as people and not just colleagues,” she says. “I want to know what people had for breakfast, what they are struggling with. That is part of their full being. My co-director has a one-year old child. That’s a reality for a lot of people in our arts network. How do we make space for this? How do we grow to include it? How do we let go of our rigid timelines and let people participate to their ability?”

Flexing across a Leadership Spectrum

Real tensions often emerge when people shift from dominant culture models of top-down, command and control, directive leadership to embrace a leaderful ecosystem. At Chinese for Affirmative Action, these tensions have resulted, at times, in confusion and disagreement about who is listened to, who gets to define problems and solutions, and who is responsible for leading. To develop greater flexibility, we acknowledged the norms and expectations that were already in place and then attended to clarification and communication about roles and responsibilities. This allowed leadership to emerge in many places within the ecosystem.

For leaders in leaderful ecosystems, our challenge and opportunity is to understand when and how to shift from a more directive approach to a more collaborative approach, and vice versa.

- More Directive Approach: When successful solutions are known or there’s wide agreement about what to do, leaders are able to act quickly and decisively. However, for many of our clients and partners, it is important to actively consider how directive leadership can be developed in ways that align with our values and can be exercised by people throughout the system. In this way, directive leadership becomes an effective approach in specific contexts that can be put to use by leaders at all levels, not just positional ones.

- More Collaborative Approach: With adaptive challenges, there is rarely one prescribed set of solutions. In these situations, it is critical to ask good questions that bring together the wisdom and perspectives of multiple people. Working in this way, the group and its leaders (formal and informal) work from the core belief that everyone together is the expert on the problem and holds a share of what’s needed for transformation to occur. Showing up at this end of the spectrum does not mean abdicating leadership; instead, it means turning down the volume on self-importance and the tools, strategies and structures that may have worked in the past—but are no longer working—and making way for what’s possible through collective wisdom, power, and action.

As Patrisse Cullors-Brignac and Alicia Garza, two of the three co-founders of Black Lives Matter, have written, “When we center the leadership of the many who exist at the margins, we learn new things about the ways in which state sanctioned violence impacts us all. And what we have learned…is that when a movement full of leaders from the margins gets underway, it makes the connections between social ills, it rejects the compromise and respectability politics of the past, and it opens up new political space for radical visions of what this nation can truly become.”

For our clients and partners in the field, what’s most important is that people are learning to flex along this spectrum from technical/directive to adaptive/collaborative “in ways that continue to build toward shared goals, along common values, and that preserve flexibility rather than in-service of ego.” This can be difficult because we routinely default to one side of the spectrum or other. Thus, those of us in positions of authority need to build “the readiness and capacity of [ourselves] and others to respond appropriately given the challenges at hand and the group’s shared purpose.” With this, the entire system can benefit from the elegance and efficacy of flexing across the leadership spectrum.

Valuing Multiple Ways of Knowing, Voices and Perspectives

Nurturing a leaderful ecosystem necessitates uplifting the wisdom and contributions of multiple sources and perspectives to engage multiple ways of knowing. In her work with cities to advance collective impact, JaNay Queen Nazaire and her partners at Collective Impact/Living Cities are tackling problems that are so big “no one individual or individual organization can make the change.” To draw on different experiences and knowings, they are co-creating cross-sector tables (or collaboratives) where public sector leaders and nonprofit, philanthropic and private sector organizations come together to address complex problems.

No one organization can ensure all children in Philadelphia are ready for kindergarten or that all African American men in New Orleans are able to make family sustaining wages. To solve these problems it takes significant changes in terms of policy, practice, and capitalization.

This can only be achieved when people develop trusting relationships and actively seek out, listen to, and share one another’s perspectives.

Beyond enlarging our understanding and perspectives, this work also requires that we bring all of our wisdoms to bear. In her book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants, Potawatomi writer, scientist, and mother Robin Wall Kimmerer shares her experience of growing up near wild strawberry fields. These strawberries were gifts whose succulence and sweetness grew with her gathering and giving of them to others. And, too, her harvesting of the berries created space for the plant to send out new red runners and thus produce new plants and additional fruit. It was a reciprocal relationship, one between human and plant, that Kimmered honored by giving thanks to the strawberries, the ode min or “heart berry” in Potawatomi, and by sharing their bounty with those she loved. Such an act of gratitude is a meditation on the interconnectedness of all things—a prayer.

In the Ojibwe (Anishinabeg) language (of one author’s heritage), the word for praying is anama’etaw. It is an animate verb, which means it is living, breathing, alive. By creating leaderful ecosystems, we are nourishing reciprocal and fertile ground for our collaborations. And in this way, we are offering a prayer to the bountiful natural, ancestral, spiritual world, drawing on its wisdom, and bringing forth these multiple ways of being and knowing. Notes Kimmerer, we are “bestow[ing] our gifts in kind, to celebrate our kinship with the world.” We are being leaderful.

Creating the Space for Inner Work

The path to justice is long and convoluted, and it’s often extremely hard on the practitioners. Attending to one’s own well-being as well as that of the larger ecosystem is crucial. Just as the trees have shown us, our shared mutuality requires the health of each of us to strengthen the health of the forest and vice versa. In the words of Patrisse Marie Cullors-Brignac, “My being alive is actually a part of the work…[To] reclaim our bodies and our health is a form of resistance.”

At Management Assistance Group, we are paying fierce attention to individual and collective well-being. We’ve enacted practices and put in place policies to prioritize personal sustainability. In order to grapple with the continual process of balancing and rebalancing needed, we discuss the impact of these policies regularly to ensure they are creating the desired effect. We also make space for our whole selves to come forward through the integration of meditation, breathing, and artistic practices into our meetings and discussions.

For our partners working in network movement spaces, there is an increasing focus on sustainability, both at the level the individual and the broader movement. This manifests in new ways of thinking about and holding expectations of one another and in making decisions that support our long term, healthy engagement. By attending to our inner work and wellbeing, we are cultivating a deeper resilience rooted in strength and the capacity for joy.

We hope you’re enjoying this series, “Five Elements of a Thriving Justice Ecosystem,” which began with “Pursuing Deep Equity.” The next in the series is “Multiple Ways of Knowing: Expanding How We Know.”