January 20, 2014; AFL-CIO Now

Five years ago yesterday, Barack Obama was inaugurated as the first black man to be elected president of the U.S. Fifty years ago this year, thousands of people risked their lives to participate in Mississippi’s “Freedom Summer,” or, more formally, the Mississippi Summer Project, which saw thousands of people arrested, scores of churches and homes bombed or burned, hundreds of people savagely beaten, and several killed—most notably James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman in an ambush by the Ku Klux Klan.

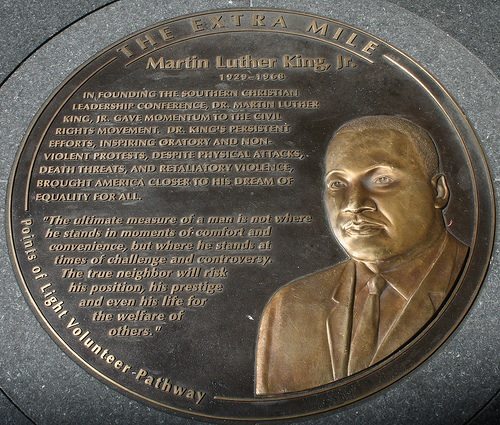

The point of Freedom Summer was to register black Mississippians to vote in the state that at the time had the lowest proportion of eligible black voters actually registered. At the time of his point-blank murder, Goodman was a summer volunteer, while Chaney and Schwerner were activists working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Our nation doesn’t have to witness more people like Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman beaten by vicious racists to honor the memory of those volunteers in 1964 or the role of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in guiding this nation toward greater racial justice. However, the annual one-day “Day of Service” that the U.S. seems to miss the mark of honoring the volunteerism of the likes of Goodman and the thousands of others who marched for fundamental rights.

The government website on MLK Day service opportunities goes to a page associated with Points of Light, on which prospective volunteers could have inputted their cities or zip codes to find Day of Service volunteer opportunities. For metro Washington D.C. (in which President Obama and his family volunteered at the DC Central Kitchen), the first page of volunteer opportunities included the following:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Volunteer gardening at the National Arboretum

- Helping at the 40th anniversary of the Arlington (Virginia) Arts Center

- Cleaning classrooms at the Maury School in Arlington used for children’s and adults’ art classes

- Helping with the open house at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- Training for volunteers who might be called on to work at Volunteer Reception Centers should a disaster strike Arlington

- Opportunities for persons 55 years old and older to volunteer at the Shirlington Public Library

- Volunteer opportunities for students with park restoration and trail building in Montgomery County’s (Maryland) Conservation Leadership Corps

- Hosting events for National Drug Facts Week

- Sorting potatoes for distribution to food pantries and shelters at Christ Church in Kensington, Maryland

- Volunteering to educate people about Affordable Care Act open enrollment and to schedule appointments with health care “navigators”

- Volunteer opportunities associated with the “I Promise” Skating for Concussions fundraiser in Silver Spring, Maryland

- Volunteering for the Japan Commerce Association of Washington festival

They are all valuable and positive volunteering opportunities, but they don’t necessarily get to issues of race, civil rights, racial justice. Recently, CNN Crossfire co-host Van Jones cited King’s “I have a dream” speech to suggest that the meaning of the holiday is to focus not on the past but, like King’s message, on a vision of the future. “What’s the future we’re fighting for now?” Jones told an audience in San Rafael, California. “Because if you can’t explain that to people, you’re just going to have a bunch of bad statistics, some interesting legislative proposals, and a bunch of white guilt…and very little progress in these (underserved) communities.”

No work toward civil rights and racial justice is insignificant, but what does that entail? At yesterday’s Martin Luther King Day celebration and march in San Antonio, Texas, AFL-CIO president Richard Trumka offered a compelling definition of what still needs to be addressed in this nation’s movement toward racial and overall socio-economic justice:

“Deep in my heart, I believe America is ready for a groundbreaking new movement for civil rights, for workplace rights, for immigrant rights, for LGBTQ rights and for human rights. I’m talking about an increase in the minimum wage. Universal sick pay. I’m talking about job creation. And other measures to stop the collapse of working people in America. These are not luxuries but necessities. America is hungry, sisters and brothers. America hungers for justice today.”

It’s not hard to imagine these words from Trumka, a former United Mine Workers leader, who helped engineer the UMW’s support for striking mineworkers in South Africa, receiving the approval of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In an odd historical anomaly, the Freedom Summer protests of 1964 led to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, though the gap between the law and a reasonably full implementation of the law took decades. In the past few years, voting rights for people of color began to take a negative turn as state after state enacted restrictive “voter ID” laws that were transparently about the reduction of turnout and participation by black voters. This was followed by a Supreme Court decision that undid the Section 4 enforcement provisions of the Voting Rights Act. Despite the passage of 50 years, there are still continuing shortfalls in the legal rights of black persons in the U.S. that reflect the injustices that Martin Luther King Jr. fought to overcome—and that are rarely if ever broached by the apolitical kinds of volunteerism promotion associated with the annual “Day of Service.”—Rick Cohen