September 24, 2017; Washington Post

The nation’s capital is certainly familiar with gentrification. A generation ago, Blacks were 70 percent of city residents. By 2015, that number had fallen to 49 percent due to a combination of an influx of wealthier and whiter residents and the departure of many Black residents, who moved to more affordable places outside the city as rents and property taxes rose. Since 2010, Washington, D.C.’s population has climbed by 79,000, a 13 percent increase. And, as this map from Governing makes clear, gentrification’s impact can be found in an astonishing 54 of the what were the District’s 104 low-income census tracts at the start of the century.

Most of the city east of the Anacostia River, however, has not gentrified—not yet. But a new $45 million project patterned after New York City’s High Line Park may begin to change that. Called the “11th Street Bridge Park” and slated to open in 2019, the park will convert an abandoned freeway bridge into an aerial park “connecting the east and west sides of the Anacostia River with recreational open space that will span the length of three football fields.”

As Post reporter Mary Hui explains:

The project’s architects envision residents from across the city converging on what they hope will be a world-class civic space with amenities including an amphitheater, community farm, hammock grove and art installations. But they also fear that the park will spur a big jump in adjacent property values, potentially pricing out residents east of the river.

Scott Kratz, project director for the local nonprofit Building Bridges Across the River, a leading park construction partner, says one of the biggest questions they face is “How do you invest in places of need without displacing the people you’re trying to serve?” The answer folks in Washington have come up with is called a community land trust.

What is a community land trust? As Jake Blumgart in Slate explains:

Community land trusts are nonprofit organizations, with a board composed of representatives of the public, the local government, and the tenants, that obtain land and either develop it themselves or lease it to developers. The trust then removes its holdings from the private market, usually through 99-year ground leases and pre-emptive purchase requirements that limit how much the house can be sold for.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

How does this work? Say a home costs $250,000, but the most residents can afford is $200,000. A city housing agency could use homeownership funds like the federal HOME program (and state and local programs too) to buy out the difference with a $50,000 “second” that is payable on sale of the home or perhaps is made “forgivable” if the buyer stays for five years or more. This is a great deal for the buyer who wins the funding lottery—but thousands get nothing. For example, if the price went up to $400,000, the family would make $200,000, but the city might have to pay four or five times as much per family to maintain affordability for anyone else.

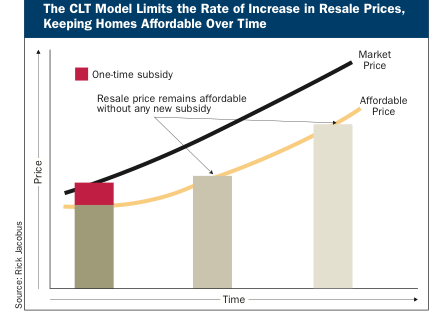

A community land trust works very differently. The resident still buys the home for $200,000, but because the trust owns the land, most of the equity stays with the trust. The exact split is outlined in the deed. Typically, the family is entitled to reimbursement for improvements plus a percentage of equity gain (often 25 percent), which studies have shown is often still enough to enable a majority of families to “step up” into standard housing afterward. The remaining equity stays with the trust, enabling the trust to make the house available at an affordable price to the next family with no additional subsidy, as the graph below from a Lincoln Institute of Land Policy study by Rick Jacobus and John Emmeus Davis shows.

Land trusts are also a powerful mechanism in poor markets, since the lower buy-in price for families helps avert foreclosure. During the Great Recession, families occupying land trust housing faced foreclosure at one-eighth the rate of those in standard housing arrangements.

For a long time, community land trusts have seemed like the next big thing among many housing advocates. The benefits of community land trusts (and limited equity housing cooperatives) in creating a middle ground between renting and owning have been obvious to housing experts for a long time. But the complexity of the arrangements, as well as resistance to change (“What do you mean I have to share ownership?”) have slowed growth.

That may be changing. As Hui notes, “Across the nation, the land trust movement is gathering steam.” In addition to D.C., Hui herself cites similar developments in the past year in New York City (which launched a $1.65 million program this past July), Pittsburgh (which launched a community land trust in June), and Baltimore, where Mayor Catherine Pugh has endorsed the strategy as part of a proposed $40 million affordable housing effort. The national Black Lives Matter network and the New York City-based National Economics and Social Rights Initiative (NESRI) are among the growing number of social justice groups advocating this approach. Nationally, there are now 330 community land trusts, up from 242 six years ago.

Of course, no one mechanism will avert gentrification alone. And skepticism is surely warranted regarding whether the modest sums dedicated to land acquisition in Washington are anywhere near what is needed. But at least the District’s effort is a good start. As Kratz puts it, in building infrastructure like the 11th Street Bridge Park, the city needs to be “intentional in ‘ensuring we’re answering the question of who this is for’—residents.”—Steve Dubb