“NEW BEGINNING” BY LEMYRE ART/WWW.LEMYREART.COM

Editors’ note: The following mini–case studies were submitted as part of the graduate course “The Nonprofit Sector: Concepts and Theories,” taught by Chao Guo, associate professor of nonprofit management in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Below is an introduction by Mark A. Hager, associate professor of philanthropic studies in the School of Community Resources and Development at Arizona State University. This article is featured in NPQ’s new, winter 2014 edition, “Births and Deaths in the Nonprofit Sector.”

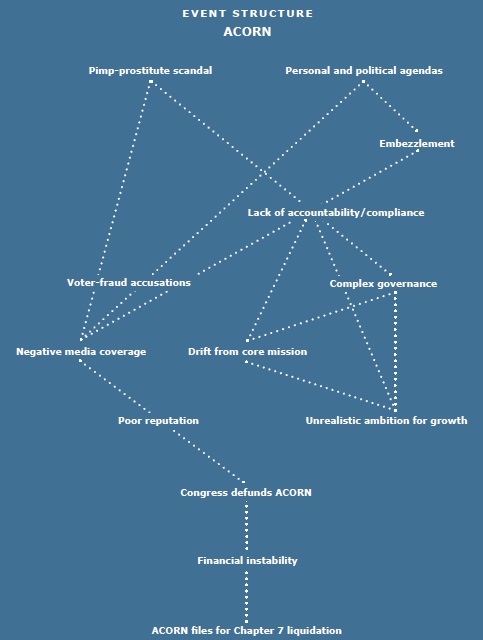

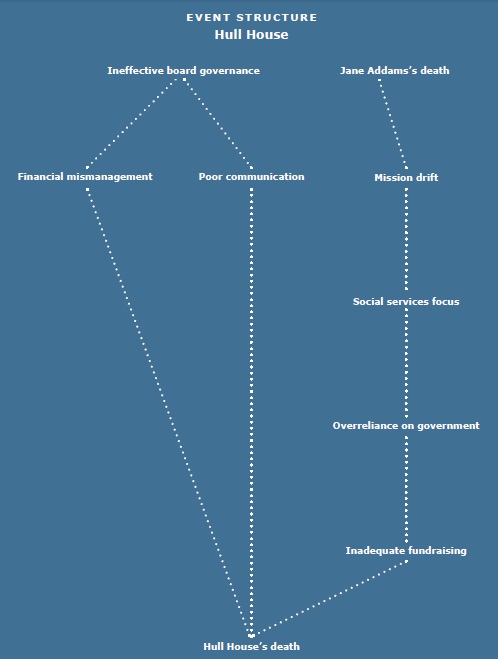

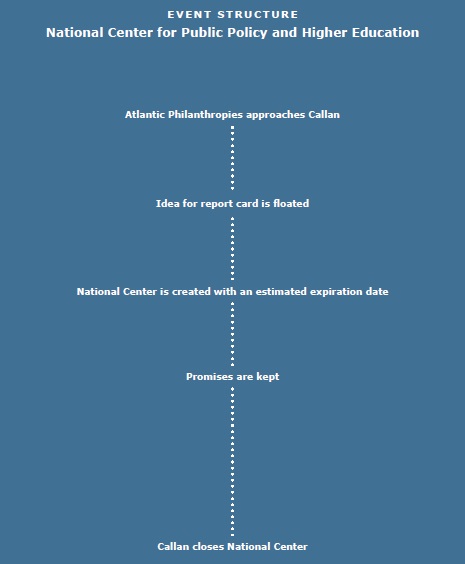

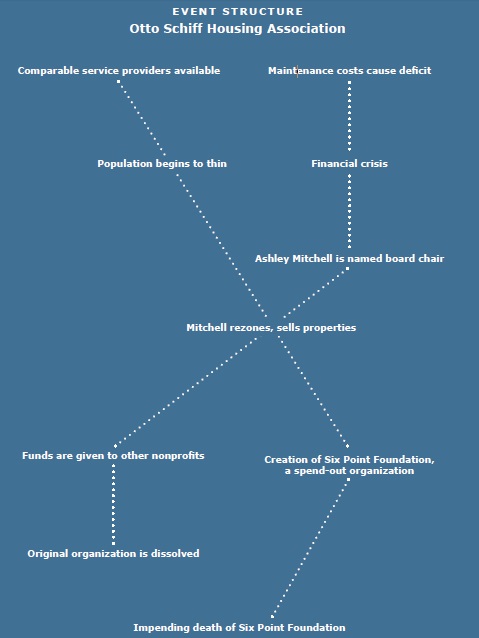

Organizational events are complicated, so we have to select the right tools to study and understand them. Statistical models are all the rage, but they are poor choices for studying intricate processes. The stories and the analytic tools we have to interpret them are better at capturing the complexity, but while stories by themselves can teach us a lot, they cannot show us the similarities or trends that run across an assortment of cases. One approach to understanding the trends in stories is called “event structure analysis.” Pioneered by Indiana University sociologist David Heise in the early 1990s, event structure analysis has been used to understand social movements, labor markets, firm growth, and organizational decline and dissolution, to name just a few areas where it has been applied.

The five cases in this article include “event structures” that are a hallmark of the method. You can think of them as a graphical representation of the events in the case, but they are more than that. The connecting lines do not just signal that one event led to another—they mean that the person studying the case believes that one event was actually involved in causing the subsequent event to happen. (This is not to say that the subsequent event had to happen, only that it did.) When we see events unfolding in similar ways across a variety of cases, we can build our understanding of how change processes unfold in nonprofit or other kinds of organizations.

The interpretations of the people who studied the cases (the individual authors of each case study) are important to the method. Authors or author teams used Heise’s program Ethno (available online) to document and create their event structures.* The first step is to boil the cases down to essential events, resulting in a terminal event (like closure or merger). A simple case might have only several events; a more complicated case might have several dozen. Once the events are listed, the analysts enter them one at a time into the computer program. Once entered, Ethno starts asking the analyst a series of questions about the relationships between events. Was Event A required for Event B to happen? Was Event B required for Event C? And so on. Analysts consider the situation and answer yes or no. Once Ethno understands all the logical relationships between chains of events, it can draw the event structure. Like the story, the event structure can be informative on its own; however, when coupled with other cases that went through similar or different processes, we can build broader understandings of organizational life and death.

Mark A. Hager

Arizona State University

*See www.indiana.edu/~socpsy/ESA/.

The Death of Hull House

by Daniel Flynn and Yunhe (Evelyn) Tian

Much has been written about the unexpected closure of Jane Addams’s Hull House in January of 2012. This venerable institution had served some of Chicago’s most vulnerable residents for over 122 years. Many have chalked up the closing to Hull House’s overreliance on government funding, and no doubt this is partially to blame. However, that diagnosis is, we feel, oversimplified—financial mismanagement, poor governance, and severe mission drift all contributed to Hull House’s untimely demise. We also wonder if perceived causes of turmoil, or even organizational death, cannot sometimes be in reality symptoms of a greater, more ravaging illness. Although the death of Hull House does not fully exemplify this phenomenon, the answer would appear to be yes.

A Brief History of Hull House

Hull House opened on September 18, 1889, at the corner of Halsted and Polk Streets, in a Chicago neighborhood heavily populated with recent immigrants. Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr founded this settlement house—one of the first in the United States, and eventually the country’s most famous—on the premise that “the dependence of classes on each other is reciprocal; and that as the social relation is essentially a reciprocal relation, it gives a form of expression that has peculiar value.”1 In practice, this looked like members of the middle and upper classes moving into not only a poor neighborhood but also the same house as their disenfranchised neighbors. Originally, these elites came to Hull House to address poverty through various education and cultural classes and activities. However, for many who stayed on and got to know those they came to help, “their class condescension evaporated and was replaced by democratic beliefs: outrage at the unjust conditions working people strove to overcome and eagerness to be their political allies in those struggles.”2 From its early days, Hull House exhibited a strong dualpronged mission: assist the impoverished and vulnerable of society with basic needs and cultural competencies, and advocate for the rights and dignity of each citizen.

Jane Addams remained at Hull House until her death, in 1935, and Hull House continued to change and evolve once Addams was no longer at the helm. By the time of her passing, Hull House had grown from one settlement home into thirteen houses that comprised the Hull House community. Hull House had also become a hotbed of political activity—hosting women radicals and academics seeking social reform, conducting research on societal injustices ranging from cocaine use to inadequate sanitation, and working with city officials to establish Chicago’s first public swimming pool, public gymnasium, public playground, and citizen preparation classes.3 In the 1960s, Hull House was displaced by expansion of the University of Illinois and lost its original settlement house structure, becoming instead a system of community and neighborhood centers around Chicago. And in the 1990s, the economic growth of the period encouraged the organization to reshape its operations to focus on foster care, child care, domestic violence counseling, and job training. The financial boom allowed Hull House to quadruple its budget and confidently enter the twenty-first century.

The Closing of Hull House

Unfortunately, the twenty-first century did not bring continued prosperity for Hull House. In mid-January of 2012, Hull House announced that it would be forced to close in March. In fact, it closed just one week after that announcement, on Friday, January 25. Nearly three hundred employees and upward of sixty thousand yearly clients received less than one week’s notice. The chairman of the board, Stephen Saunders, asserted that Hull House “hoped for a much more dignified closing” and that the organization had debt of “approximately $3 million and growing, owed to vendors and landlords all over Chicago.”4 There was simply not enough money to continue daily operations.

What caused the demise of such a famous and revered institution? How did it happen so abruptly, unforeseen by staff and with limited pleas to the public for support? Were there warning signs of impending death? And what can Hull House’s closure reveal about the death and dying process of nonprofit organizations?

Mismanagement

The death of such a well-established, iconic nonprofit organization inevitably raises many questions about mismanagement, especially given its extensive executive team and the many accomplished professionals—including at least five financial advisers, five attorneys, and several CEOs—who served on its board of trustees.5 The management failures at Hull House can be organized into two primary categories: financial negligence and poor governance.

Financial Negligence

The only financial documents available for Hull House span 1998 to 2010, but they show significant signs of economic distress over that thirteen-year period. By 2010, Hull House had entered the “‘zone of insolvency,’ a period of financial distress where […] the legal responsibilities of board members change from […] safeguarding their organization’s mission and assets, to safeguarding the interests of all of its stakeholders.”6 With better financial management, Hull House could have avoided this crisis, and simple financial analysis supports this claim.

First, basic financial analysis reveals revenue drops of nearly 19 percent between 2001 and 2002 ($40,567,863 to $32,932,988), as well as a continuous decrease in total revenue from 2007 to 2010, totaling 27.3 percent ($32,011,227 to $23,286,579).7 In addition, when looking at the various revenue sources and expense categories, one finds that almost 90 percent of Hull House’s revenue came directly from government payments, and this percentage peaked at 95.2 percent of total revenue in 2001. On average, less than 10 percent of revenue came from public contributions, and only about 1.5 percent of total expenses each year were spent on fundraising.8 The lack of diversified revenue, overreliance on government contracts, and poor fundraising performance were all substantial indicators of poor financial planning.

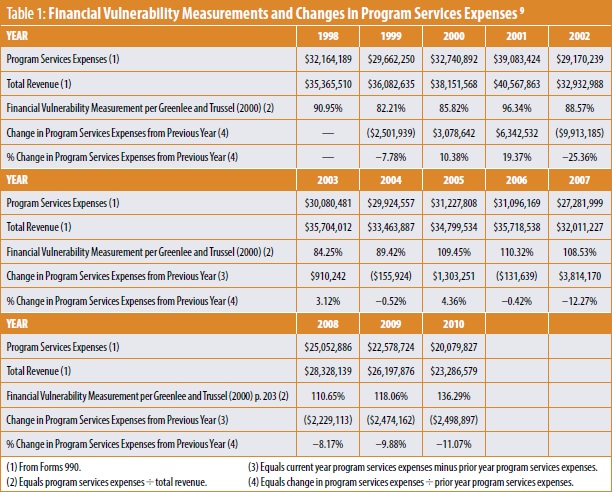

Second, there were also clear warnings of Hull House’s high level of financial unsustainability from the financial vulnerability measurement. This tool takes program service expenses divided by total revenue, and indicates whether or not an organization generates enough revenue to support its program functions (not even taking into account administration or fundraising expenses). As table 1 shows, Hull House consistently had vulnerability measurements near 90 percent, and, after 2005, yearly rates exceeded 100 percent. By the late 2000s, Hull House was unable to financially support its programs, and it never took drastic enough measures to overcome those deficits.

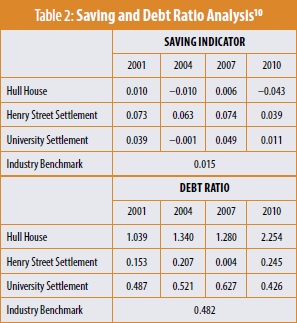

Third, ratio analysis comparing Hull House with other similar settlement houses and industry benchmarks further paints the picture of an organization in financial crisis (see table 2). The savings indicator, calculated by dividing net income by total expenses, measures what percentage of revenue an organization saves each year. The common industry benchmark for large human needs organizations is .015, and Hull House not only never reached this threshold during the 2000s but also was consistently outperformed financially by two other well-known settlement houses: Henry Street Settlement and University Settlement.

Likewise, as table 2 shows, the debt ratio also reveals Hull House’s poor financial performance. This indicator, calculated by dividing total liabilities by total assets, measures the riskiness of an organization’s debt structure. A lower result signals a healthier organization with less financial risk; Hull House’s industry benchmark is slightly below .5. Hull House again performs poorly, with debt ratios doubling, tripling, and even quadrupling this industry standard.

Nonetheless, despite poor debt ratios, this measurement only tells part of Hull House’s story. First, accounts receivables consistently made up as high as 40 percent of total assets, and these were mostly from government contracts that were often paid late.11 Therefore, there were deep cash- flow issues that the ratio does not reveal. More significantly, however, US GAAP principles do not require property to be listed at fair market value, and Hull House’s properties—many of which were bought decades prior and had been greatly depreciated—were listed at low values or had been removed completely from the balance sheet. For instance, despite owning numerous community centers around Chicago, Hull House’s 2010 Form 990 lists only $930,049 in land, buildings, and equipment, meaning that the organization had significantly more assets than were listed.12 Given the growing organizational debt, one must ask why Hull House did not choose to sell some of these valuable properties to cover its increasing liabilities.

A final indicator of Hull House’s financial distress was its exceedingly high leverage, both in terms of current and long-term liabilities. This is especially evident upon examining Hull House’s “other liabilities” presented in its 990s. This broad category of debt included loans from the Hull House Foundation, unfunded pension payments, checks drawn in excess of deposits, and government contract advances. Of special concern were the cash advances Hull House received on its government contracts for over $2 million on an annual basis, from 1998 to 2005, and for over $1 million from 2006 to 2010.13 Ultimately, these “other liabilities” reveal that Hull House remedied its cash flow and fundraising issues by “spending tomorrow’s funding to pay for yesterday’s expenses.”14 This irresponsible cycle could not last forever, and it contributed to organizational death.

The signs of financial mismanagement at Hull House seemed to be everywhere: decreasing and undiversified revenue, inability to fund program operations, lack of yearly surpluses, unrestrained debt growth, and poor debt management. There is little doubt that Hull House suffered a dearth of financial stewardship, yet this failure only caused such irreparable destruction because it was coupled with poor governance.

Poor Governance

One of the key turning points for Hull House was when it hired Gordon Johnson, former director of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, to lead the organization. Johnson increased the annual budget of Hull House from about $9 million in the 1990s to $40 million in 2001, largely by relying on government funding, which has been discussed previously.15 When Clarence N. Wood succeeded Johnson, in 2001, he promised to bring more private funding to Hull House to offset the continuous cutting back of Illinois’s government budget for human services—$4.4 billion from 2002 to 2012.16 However, it is clear that Wood never achieved this goal, nor did he address any of the other emerging financial problems. Yet ultimate financial responsibility for a nonprofit does not lie with the executive director but, rather, with the board of trustees. Though the board claimed it did everything it could to save Hull House, fiduciary irresponsibility and poor communication—both internal and external—suggest otherwise.

One of the three legally required duties for nonprofit boards is the “duty of care,” a responsibility that requires board members to “participate in well-informed decisions on behalf of the nonprofit.”17 With such overt signs of financial distress in Hull House’s yearly financial statements, serious questions remain as to whether or not the Hull House board fulfilled this responsibility. One can posit that a board comprised of successful business people—a number of whom worked in the financial sector—would be able to accurately interpret basic financial documents. If this is the case, board members either did not take the time to carefully review these documents—which would mean they violated their duty of care—or failed to take sufficiently aggressive measures to improve the organization’s financial situation and correct bad financial practices. If, somehow, the board was financially illiterate, it had a responsibility to recognize and address this deficiency. The financial woes at Hull House ran deep, but with strong, active governance, these problems could have been identified and rectified before organizational death.

As suggested above, there is evidence that the Hull House board suffered from poor internal and external communication. Internally, an organizational cultural gap existed between the board members and the staff. According to Wood, some board members did not comprehend the idea of “living on the edge,” because their corporate backgrounds encouraged organizational abandonment over the struggle to survive. West reported that most staff members within Hull House were used to traditional social service models and life on the edge, and accused the board of not understanding how nonprofits really function.18 In the wake of organizational closure, board and staff blamed each other for ineffective governance and inaccurate information, respectively. In other words, there were different understandings about how to interpret the organizational situation (i.e., financial data) and how the board should address different problems (i.e., decision-making process) to achieve mutual agreement and commitment within the organization.

Externally, stakeholders criticized Hull House for not publicizing their financial problems earlier or louder and instead presenting a sugarcoated image of the organization. Upon closing, Hull House’s board chair Stephen Saunders noted that the organization had been holding six or seven fundraisers a year, and that board members had been reaching out to anyone they knew.19 Nonetheless, despite these efforts to raise additional funds, many around Chicago and beyond were stunned when the organization collapsed. By the time Hull House announced its closing, it was too late for the public to save the famous institution. The board’s reluctance to be transparent about Hull House’s true condition (or inability to recognize its precarious situation) exemplifies both a failure in its obligation to organizational stakeholders and a failure in strategic governance.

Mission Drift

Despite evidence of severe financial negligence and poor governance, one must consider the possibility that these woes were symptomatic of a different cause of Hull House’s death: mission drift. Any casual observer could note that the Hull House of 2012—in revenue sources, mission, operations, and physical structure—looked starkly different from Jane Addams’s original settlement house, and these divergences from the founding structure require further exploration.

Organizations cannot function or fulfill their missions without money, and Addams and Gates were keenly aware of this upon the founding of Hull House. In the early days, Hull House survived (in an era before tax deductions) through in-kind gifts and financial donations sought out by Addams. It was an arduous process, and she writes, “We were often bitterly pressed for money and worried by the prospect of unpaid bills, and we gave up one golden scheme after another because we could not afford it.”20 To help wealthy Chicagoans empathize with the settlement and its residents, Addams often brought donors to Hull House to share a meal with the guests or attend lectures, concerts, or other events.21 Fundraising from individuals was, for many years past Addams, the primary source of money for Hull House, yet by January 2012, 85 percent of Hull House’s revenues were from government contracts.22 Moreover, the organization struggled desperately to attract private contributions. Not only does this altered fundraising model significantly hinder the opportunity to bring together different social classes for mutual benefit—an original intent of the organization—but it also makes the key collaborative partnership not with the public but with an entity Addams viewed with suspicion: government. As Ivan Medina of the School of Social Work at Loyola University Chicago commented in an interview with Maureen West, “Jane Addams was about social change. She challenged government. [. . .] If you become an arm of government, you can’t protest government, its bad policies and unequal services.”23 Though a lack of diversified revenue sources contributed to Hull House’s closure, one must consider whether the dubious structure was not a direct cause of organizational death but rather a symptom of mission deviation.

Furthermore, and perhaps most notably, the mission and operations of Hull House had changed drastically since the early days. At its closing, the organization was serving over sixty thousand people a year through social services such as foster care and domestic violence counseling. However, though Jane Addams is often regarded as the founder of modern social work, the early Hull House services and programs differed greatly from those of today’s social service agencies. A weekly program from 1892 displays a diverse set of programs and activities, including the “Working People’s Social Science Club,” “Women’s Gymnastic Classes,” “Electricity—With Experiments,” and “Hull House Debating Club,” among many others.24 Hull House’s original approach to helping people meet their basic needs or gain life skills only faintly resembled current notions of social services. Furthermore, these “services” offered by Hull House were never central to the settlement’s mission; rather, as Florence Kelley, an early resident of Hull House eloquently put it, “The House may seem to exist chiefly for its mass of detail work, yet as the years go by the truth grows clearer, that much of this has been chiefly valuable for the fund of experience it yields as a basis for wider social action.”25 Hull House was instrumental in advocating for reforms ranging from the creation of public spaces and organizations to new labor protection laws to better sanitation services for poor neighborhoods. Eventually, the organization became not a political challenger seeking social change but instead a political instrument implementing government programs. By the time of Hull House’s untimely demise there was little question of how far the organization had strayed from its initial purpose and role in the Chicago community.

A final significant difference in the modern Hull House and its founding version was its physical structure. As was briefly discussed, Hull House was forced to sell its properties in the 1960s because of university expansion (the original Hull House home was preserved as the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum), and rather than retain a similar model with various properties in the same neighborhood—and even the same block—Hull House opted to decentralize, and instead became an expansive, often disjointed network of neighborhood centers around Chicago.26 This signaled the end not only of a single community focus but also of the cohabitation of different social classes. The Hull House Association, as it was renamed after this shift, resembled a traditional nonprofit organization more than a settlement house.

This restructuring, however, was not unique to Hull House, and nor were the drastic changes in revenue sources and operations; in fact, they were quite the opposite. Many comparable organizations underwent similar transitions: settlement houses morphed into neighborhood centers; resident social workers ceased to live in the neighborhoods they served; staff was professionalized and relied less on volunteer labor; and donations were replaced by government funds as the primary source of revenue.27 If anything, this restructuring was the norm for settlement houses, and though many organizations founded in the original settlement model have closed, many others, including Toynbee Hall in London, Henry Street Settlement in New York City, and University Settlement in Cleveland, continue to thrive today. Thus, despite Hull House’s vastly different revenue structure, mission, operations, and physical layout from its original form, it seems imprudent, given the many analogous settlement houses that experienced the same transitions, to declare mission drift the sole underlying cause of the organization’s demise.

• • •

Rather than playing the role of medical provider who establishes the illness prior to death, this study acts as a coroner who seeks to identify the cause of death after the organization’s passing. However, an “organizational autopsy” does not have the advantage of examining a deceased body; rather, it must analyze the actions and reactions of an organization when it was alive. In the case of Hull House—and many other nonprofits—this causes a conundrum: how does one distinguish between symptoms of an illness and the underlying illness itself?

If there were a single devastating cause of death for Hull House, what might that be? A compelling argument could be made that Hull House suffered from “reverse founder’s syndrome”: no subsequent leaders at Hull House possessed the prophetic vision of Addams, and the organization’s operations and integrity suffered as a result. Financial mismanagement and poor governance were merely symptoms of a sharp mission divergence at Hull House since Addams’s death. However, though a “mission purist” might prefer this argument overall, it seems to lack conclusive evidence. Other settlement houses formed with a spirit and mission comparable to that of Hull House and evolved over the years in a similar fashion as Hull House, yet these developments did not bring about financial distress or ineffective board leadership. Moreover, nonprofit missions should evolve as the organization and times demand, and Hull House thrived for many years after its mission had deviated from Addams’s original settlement-house model. Ultimately, the cause of death for Hull House was a three-pronged attack—financial mismanagement, poor governance, and mission drift—that ravaged all facets of the organization. If Hull House had managed one or two of these areas more effectively, perhaps it could have staved off death and even paved the path to recovery. Sadly, it succumbed to all three conditions.

Notes

- Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House, ed. Victoria Bissell Brown (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999), 80. Abridged reprint of 1910 edition, with related documents.

- Louise W. Knight, “As Chicago’s Hull House Closes Its Doors, Time to Revive the Settlement Model?,” The Nation, January 25, 2012.

- Rick Cohen, “Death of the Hull House: A Nonprofit Coroner’s Inquest,” Nonprofit Quarterly, August 2, 2012, dev-npq-site.pantheonsite.io/management/20758-death-of-the-hull-house-a-nonprofit-coroners-inquest.html.

- Cheryl Corley, “Jane Addams Hull House to End Immigrant Services,” NPR, January 27, 2012, www.npr.org/2012/01/27/145950493/jane-addams-hull-house-to-close; Maureen West, “Some Fear Hull House Closure Is an Omen for Struggling Charities,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, February 2, 2012.

- Shia Kapos, “Nonprofit World Wonders How Hull House Failed Given Executives on Board,” Crain’s Chicago Business, January 27, 2012.

- Barbara Clemenson and R. D. Sellers, “Hull House: An Autopsy of Not-for-Profit Financial Accountability,” Journal of Accounting Education 31, no. 3 (September 2013): 255.

- Data retrieved from “Form 990: Return for Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” FY2001–2002, 2007– 2010, Hull House Association, 01-02 filed 11/05/2002, 06-07 filed 12/14/2008, 07-08 filed 12/12/2009, 08-09 filed 05/17/2010, 09-10 filed 10/12/11, accessed September 27, 2014, www.guidestar.com.

- Clemenson and Sellers, “Hull House,” 252–93.

- Ibid., “Table 1: Financial and vulnerability measures per Greenlee and Trussel (2000), 203 and changes in program service expenses,” 258.

- Data retrieved from “Form 990: Return for Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” FY2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, Hull House Association, Henry Street Settlement, and University Settlement (authors unable to confirm file dates), accessed October 13, 2014, www.guidestar.com; industry benchmarks retrieved from Clemenson and Sellers, “Hull House,” 260

- Clemenson and Sellers, “Hull House,” 279.

- “Form 990: Return for Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” FY2010, Hull House Association.

- Clemenson and Sellers, “Hull House,” 267.

- Ibid, 266.

- Suzanne Strassberger, “Did Hull House Make a Mistake by Aggressively Pursuing Government Dollars?,” JUF News, January 28, 2012 , www.juf.org/news/blog.aspx?blogmonth=1&blogyear=2012&blo gid=13570.

- Ibid.

- Mary Tschirhart and Wolfgang Bielefeld, Managing Nonprofit Organizations (San Francisco: Jossey- Bass, 2012), 204.

- West, “Some Fear Hull House Closure Is an Omen for Struggling Charities.”

- “Fox Chicago Sunday: Stephen Saunders on Hull House Closing,” video, 5:01, from a news segment televised earlier by Fox News, posted January 27, 2012, www.myfoxchicago.com.

- Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House (1999), 105.

- Knight, “As Chicago’s Hull House Closes Its Doors, Time to Revive the Settlement Model?”

- Shanta Premawardhana, “Learning from Jane Addams and the Closing of Chicago’s Hull House,” Scupe (blog), February 6, 2012, scupe.org/learning-from-jane-addams-and-the-closing-of-chicagos-hull-house/.

- West, “What Would Founder Jane Addams Think of Hull House Demise?,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, February 2, 2012.

- Addams, Twenty Years at Hull-House (1999), 208-213.

- Ibid., 224.

- Cohen, “Death of the Hull House.”

- Barbara Trainin Blank, “Settlement Houses: Old Idea in New Form Builds Communities,” New Social Worker 5, no. 3 (Summer 1998).

Daniel Flynn is a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Flynn has worked for the Jesuit Volunteer Corps and the Health Federation of Philadelphia, among other nonprofits. Yunhe (Evelyn) Tian is a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Tian holds a practicum position as assistant to the executive director at Weavers Way Community Programs, a nonprofit committed to strengthening the connection between agricultural sustainability and healthy living.

The (Planned) Death of a Nonprofit: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education

by Barbara Berreski

How do you spark a national conversation about higher-education policies, gain the attention of legislators and other policy-makers in every state across the country, evaluate the success of higher education in each state, and present the data so that the concepts are easy for people outside the field to understand? You issue a statewide higher education “report card,” and then you call the press.

From 2000 to 2008, the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education issued five biannual reports titled Measuring Up. States were graded in six areas: preparation, participation, affordability, completion, benefits, and learning. There were many bad grades—Ds and Fs—for many of the states. And, not surprisingly, many people were upset. But it got them talking about higher education.

Establishment of the National Center

The idea for the National Center started in the late 1990s, when Patrick M. Callan, director of the nonprofit Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), was approached by Atlantic Philanthropies.1 Callan was well known in higher-education policy circles, as he had been working in the field since the early 1970s. Atlantic wanted to examine higher-education policies among the states and help them to set their agendas for the future, so Atlantic contacted Callan. The staff and the board of directors of HEPI, under Callan’s leadership, began eighteen months of intensive research. Could Atlantic’s vision be implemented? If so, how?

One idea was a report card on higher education. As Callan described it, his team liked the idea of a report card that would evaluate state performance in higher education regardless of the different policies that had been adopted state by state. In addition, the report card would gauge the success of higher education from the students’ perspective. Quality in higher education had always been measured through accreditation, which is centered on the institution; Callan hoped that the report card would change that focus.

HEPI did a yearlong feasibility study to see if there were enough data that would be relevant to good policy. They concluded that enough data existed and that a report card was an idea worth trying. At the time, Callan told me, they didn’t know if it was going to work or what the response would be.

HEPI had previous experience evaluating the performance of higher education, but not on this scale: HEPI was established in 1992 to conduct nonpartisan analyses and policy studies of higher education and disseminate the results through publications and public programs. From 1992 to 1997, HEPI sponsored the California Higher Education Policy Center, which addressed the future of higher education in California.2

Callan’s success in California had clearly interested Atlantic, but his experience had taught him that if the report card idea attracted attention there would be controversy. “We never set out to create gratuitous controversy in California, but if you do something with integrity, you are going to piss people off,” Callan said. Atlantic and subsequent funders like the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Ford Foundation knew this was a risk but over the course of the National Center’s existence never wavered in their support nor pressured Callan to “back off.”

The next step was creating an entity to support the report card; that entity, the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, was officially announced in March 1998 by James B. Hunt Jr., then governor of North Carolina. Governor Hunt served as the chair of the National Center’s board, and his participation in the endeavor gave it and its products instant credibility.3

Callan envisioned the National Center as an independent policy forum, much like the Truman Commission in the 1940s and the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education in the 1970s. He also envisioned that, like those two commissions, the National Center would exist for a period of time then cease operations.

Measuring Up and Other Projects

Measuring Up. The first edition of the report card was issued in 2000. The National Center’s goal was to show the states what they were doing well in higher education and what they were not. If a state was not doing something well, policy-makers in that state could look at other states for examples of success. In grading the states, performance was the only measure; the policy of the states was not analyzed, and the states did not get “points” for trying. “The ‘grades’ were just a device to get the message out,” Callan explained.4

Callan knew that the higher-education establishment would likely not be receptive to the idea and might choose to ignore it; thus, in order to have impact, the National Center would need to get media attention on the report. The center actively sought that attention, and the strategy worked. Callan and his staff members were invited to speak to legislatures around the country, as well as to organizations like the National Governors Association and the National Conference of State Legislatures. Sometimes they were met with enmity, but, according to Callan, they “were happy to be challenged.”

Associates Program. In 2000, the National Center established an associates program designed to foster the professional growth of individuals in higher education. As Callan put it, “If an organization is going to be sustained, it is all about developing people.” The program’s purpose was to give early-career and mid-career individuals an opportunity to meet with senior people in the field to share knowledge and consider broad policy issues.

One of the most important goals of the program was diversity of all types: “demographic, professional, and geographic.” To that end, the first group consisted of ten individuals from different parts of the country, who met for three extended weekends throughout the course of a year. The program operated for seven years, and nearly one hundred people completed it. The participants evaluated the program annually, and high levels of satisfaction were reported.5

National CrossTalk. National CrossTalk was the National Center’s periodical between 1997 and 2011. Published three to four times annually, it was designed to be a vehicle for exploring the possible solutions to the higher-education issues brought to light in Measuring Up. As Callan described it, “Those of us in social science, we can be good analysts but lousy storytellers. I knew a good story would help people connect with and understand the issues.” This approach was all part of the National Center’s strategy to help make higher-education policy issues part of a national discussion.

Callan was clear that the purpose of CrossTalk was not to promote the National Center; it was to examine how policy issues impacted real people. To that end, he hired a former Los Angeles Times education reporter to be the senior editor of CrossTalk, and CrossTalk hired freelance reporters to examine higher-education stories from both sides. The reporters were never told what position to take. NationalCrossTalk was very successful, in large part because, said Callan, “if you make it about the issues, and less about ‘me versus you,’ the more likely you are to be listened to.”6

Closing the Center

When the idea of the National Center was set forth in a concept paper in 1998, one of its missions was “to conduct public policy research and studies in areas relevant to the higher-educational needs of the nation over the next 15 to 20 years.” When the National Center announced its closing in a Cross-Talk editorial in December 2010, Callan declared that at its inception, “we expected the National Center to operate for about ten years.”7 When asked about this apparent discrepancy, Callan acknowledged that although he had not announced a specific time frame for the National Center’s existence, it was always understood that it would have a finite life of about a decade—notwithstanding the fifteen to twenty years of public policy and research the center originally intended to conduct.

To that end, Callan kept the staff relatively small—fifteen employees at the most. Although there was enough funding to double the staff, Callan felt that “smaller is good.” Not only did the small staff allow the National Center to be nimble in response to changes, it also enabled all employees to be part of the conversation. And, because the center was not a large organization, it would need to reach out to other groups involved in higher-education research and use them as resources, helping to overcome the “us versus them” mentality that sometimes pervades higher-education research.

Why

The question that begs to be asked is, Why create a nonprofit organization with an expiration date? Callan’s response was simple: “No one asked me to create a center for the ages.” But the reasons are a little more complicated than that.

First, Callan has done this before. When he helmed the California Higher Education Policy Center, he announced at the outset that it would operate for five years only—and it did. In retrospect, he regretted the specificity with which he had stated its demise (indeed, he admitted to feeling that the deadline had been a little too rigid and thus had been intentionally vague about how long the National Center would operate when it first opened). But he stayed focused on his mission and successfully completed it in the five-year time frame. Callan is, clearly, comfortable working on time-restricted projects (of course, undertaking policy research in a discrete subject area like higher education lends itself more easily to a finite time frame than some other nonprofit goals, such as, for example, ending world hunger).

Second, the impermanence of the National Center gave Callan a lot of freedom. For Callan, an organization that is not created to be permanent can take more risks, and “you need to take prudent risks to change policy.” A permanent organization might be worried about losing funding if it takes certain policy positions. Callan did not have that pressure. Callan’s funders were 100 percent supportive of the National Center’s mission, but, he said, “if the funding hadn’t been there, I would have just closed the place.”

Third, the National Center’s most visible product, Measuring Up, was a victim of its own success. This report card on the states got a lot of attention, especially in its first year. By the time the fifth edition was published, in 2008, it had, according to Callan, become part of the landscape. Politicians and other policy-makers, who at first reacted with anger and suspicion, eventually learned to use Measuring Up for their own purposes.8 In addition, much of the shock was gone after the first edition, since people knew what to expect. Callan opined: “Are you going to keep doing [something like the report cards] until no one reads your reports? Or until no one funds you?”

How

Unlike many nonprofits, the National Center did not close because of lack of funding—it was well funded at its inception and throughout its life. The National Center began with a grant from Atlantic Philanthropies, and in 2002 and 2003 Atlantic gave the National Center grants totaling $6.5 million and $2 million, respectively.9 Even at the end of its life, the National Center was still being funded. In 2011, the year it closed, it received $330,290 in grants and contributions.10

Callan has said that the National Center operated longer than expected so that it could produce the 2008 edition of Measuring Up, which was its last report card. The decision to close in 2011 was made at the same time as the issue of the final report card (most of the center’s funding was structured as three-year grants, so the board of directors had agreed to stop seeking funding three years prior to the center’s closing.) Staff were also fully aware of the anticipated closing and thus were able to make plans for subsequent employment.

After Closing

At the time of the National Center’s closing, Callan hoped that the report card would be continued by another organization. He acknowledged that the report card would have to be reformulated, in part because there are better data now. Although several foundations were approached with the idea, however, none accepted the challenge. Callan believes the country suffers without the report card, not only because it fueled public discourse about the issues but also because it gave people at the state level leverage to advocate for changes in policy. Callan similarly hoped the Associates Program would be adopted by another entity, but to date it has not.

Although the National Center was closed in June 2011, its umbrella organization, HEPI, filed a Form 990 with the IRS for 2012.11 When asked about this, Callan said that he has kept the National Center alive as a legal entity in order to “house” projects for individuals who have funding but do not have a nonprofit in which to “park” their endeavors. He made it clear that he’s not looking for business and that the National Center will likely “go away someday.”

Notes

- Unless otherwise specified, all direct and indirect quotes from Patrick Callan are from an interview with the author.

- The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, “Reports and Publications: Other Higher Education Reports and Resources,” accessed October 8, 2014, www.highereducation.org/reports /reports.shtml.

- Doug Lederman, “(Not Really) Measuring Up,” December 3, 2008, Inside Higher Ed, www.inside highered.com/news/2008/12/03/measuring.

- William Chance, The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education’s Associates Program (San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, May 2009), 3, www.highereducation.org/reports/associates/associates_report.pdf.

- Ibid., 4.

- Patrick M. Callan, Concept Paper: A National Center to Address Higher Education Policy (San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 1998), 5, www.highereducation.org /reports/concept/concept.shtml.

- James B. Hunt Jr. and Callan, “Editorial,” National CrossTalk (San Jose, CA: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, December 2010).

- See, for example, Lederman, “No Grades for States This Year,” Inside Higher Ed, December 1, 2010, www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/12/01/measuring_up.

- The Atlantic Philanthropies, “National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education: Grantee Summary,” accessed October 15, 2014, www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/grantee/national-center-public-policy-and-higher-education.

- “Form 990: Return for Organization Exempt from Income Tax, FY2011, Higher Education Policy Institute,” filed December 14, 2012, accessed October 8, 2014, www.guidestar.com/organizations/77-0313194/higher-education-policy-institute.aspx#forms-docs.

- Ibid.

Barbara Berreski is director of Government and Legal Affairs of the New Jersey Association of State Colleges and Universities (NJASCU) and a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Transformation of the Otto Schiff Housing Association, the Creation of the Six Point Foundation, and the Impending Closure of Both

by Katie Grivna and Sandi Toben

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This article examines the closure of the Otto Schiff Housing Association (OSHA), a nonprofit organization located in London that serves survivors of the Holocaust and their families residing in the United Kingdom. In 2001, after more than twenty-five years of service, board chair Ashley Mitchell determined that the best way to serve OSHA’s clients and have a greater impact on available social services would be to liquidate all of the organization’s assets and distribute the money to other nonprofits that also serve Holocaust survivors and Jewish refugees. In addition to distributing its funds to other agencies, the Otto Schiff Housing Association transformed into the Six Point Foundation, a grant-making organization that provides financial assistance to that same population.

Many nonprofits hope that their respective efficacies will put them out of business—by serving the client population fully, there would no longer be a need for such service in the future (in other words, mission accomplished). In the case of OSHA, however, Mitchell concluded that Holocaust survivors would be better served by other nonprofits in the area. And, with respect to its new foundation, as a spend-out organization Six Point plans to close in fewer than three years, when all the funds have been used.

Establishment of the Otto Schiff Housing Association

In 1933, a group of community leaders created the Central British Fund for German Jewry (CBF), presently known as World Jewish Relief (WJR), with the mission of aiding Jewish refugees. The organization played an important role before, during, and after World War II, assisting German Jews in emigrating before the start of the war, providing housing at a camp for German Jews who were at risk of being deported during the war, and helping Holocaust survivors and their families reclaim their properties and rebuild their lives afterward. According to a press statement issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) in April 1944, more than 50 percent of the thirty thousand refugees from Germany and Austria who wished to settle permanently were over the age of fifty.1

In 1955, as part of the recovery effort, CBF and AJR funded the Otto Schiff House (named after one of the founding members of CBF, who was a tireless advocate for Jews in an era of anti-Semitism)2—which housed elderly Holocaust survivors, among many other educational and supportive services.3 A brief obtained from Mitchell states that “by 1975, there were 196 refugees in residential care and 52 in sheltered accommodations”—and many more on a waiting list hoping for services.4 Programs continued until 1984, when London’s Housing Corporation decided that residential care should be separated from other services provided by CBF. As a result, in 1985 the CBF Residential Care and Housing Association was established as a separate charity and continued to care for survivors—most of whom were healthy and active sixty- to seventy-year-olds.5 In 1991, the CBF Residential Care and Housing Association was renamed the Otto Schiff Housing Association (OSHA), which managed many residential buildings, including the original Otto Schiff House.

A Decade of Decline

As the OSHA residents aged their health deteriorated, and inevitably the facilities were no longer appropriate for their needs. According to AJR’s 1989 annual report, the maintenance of the organization’s facilities wore heavily on the budget: “The facilities they provide in five homes, which include sheltered accommodation, full residential care and nursing care, can only properly fulfill their purpose if buildings and equipment are kept up to date. In an age of rapid technological and social changes this is a continuous process calling for financial support in excess of what can be diverted from ordinary income.”6 Maintaining the facilities left OSHA leaders dipping into their reserves, which were already at a deficit. In 1997, significant renovations began at the Osmond House, one of OSHA’s care homes, and construction costs quickly surpassed the budget. This restoration, combined with OSHA’s already bleak financial position, caused that year’s deficit to surpass a million pounds.7

Ashley Mitchell: Change Agent

After being a leader in Holocaust survivor services for decades and expanding its reach to five care homes and two blocks of sheltered housing sites, OSHA was losing steam.8 With debt mounting, the Housing Corporation placed OSHA on its supervision list (an intervention method) out of concern for the organization’s financial troubles.9

Failure to resolve OSHA’s deficit would result in the Housing Corporation’s seizing its assets.10 Meanwhile, trouble within the organization was also brewing, and managerial issues and bad relations between trustees caused the sudden resignation of the board chair in 1998. Mitchell, a businessman and trustee at the time, was named board chair because of his experience sorting out unruly boards.11

Mitchell, who describes himself as “an entrepreneur with a very strong social conscience,” assessed the organization for two years before deciding to close the nonprofit. While the number of Holocaust survivors was declining as the years went on, maintaining the facilities to provide an appropriate level of care continued to be a difficult task. In an interview with the authors, Mitchell explained, “The level of care we were giving was excellent but you did not have to be a nuclear physicist to realize that the situation was impossible, although there was a reluctance among many people to accept this.” He believed that the cost of sustaining operations was unrealistic and that clients would be better served through other charities. Naturally, this decision came with opposition. Mitchell spoke of the resistance he received from the chief executive that ultimately led to the latter’s resignation: “I try to allow everyone to have their say but don’t put up with irrelevant political behavior. I also absolutely believe in transparency and good corporate governance.[. . .] Not everyone always needs to have the glory,” he explained. While Mitchell respected the nonprofit’s long and rich history, he felt that other charities would better serve the same population.

Maximizing Assets

After making the decision to liquidate and distribute all of OSHA’s assets, Mitchell’s work was still far from over. Zoning restrictions on the properties significantly decreased their market price. For the next three years, Mitchell worked with architects and lawyers to remove the zoning restrictions. While these efforts came at a hefty price of £3 million, it was well worth it in the end;12 prior to rezoning, one property was valued at £2 million and afterward was sold for £30 million.13 The other properties brought in large sums, as well. According to the Jewish Chronicle Online, “Eleanor Rathbone House in Muswell Hill was sold in 2003 for £5.7 million. Then Heinrich Stahl House in Bishops Avenue fetched £16.25 million, Leo Baeck House, another Bishops Avenue site, sold for £30.25 million, and the final property, Otto Schiff House in Hampstead, is set to realise £5 million.”14 In total, property profits raised £57 million.15 Next, Mitchell made arrangements for clients to move to other local Jewish care homes, which he described as one of the most challenging aspects of the change. “Prior evidence showed that moving people who are old and frail leads to high death rates,” he said. “We managed to move everyone in the end without any associated loss of life.”

Next, Mitchell negotiated the distribution of assets to similar organizations. As he explained, “Once I had determined that we needed to close, various charities claimed historic and moral rights to our assets. These conflicting claims, which had a vision relating to general community welfare, making a bat seem to have 20/20 vision, led to a negotiation of a tripartite legal agreement, setting out how funds should be distributed. Where money is concerned most people and organizations manage to show their worst side.”

Fund Distribution and Impact

As described earlier, after liquidating its assets, OSHA distributed its remaining funds to several related organizations that serve members of the Jewish community. Most notably, close to £20 million was granted to Jewish Care, which created a nursing and dementia care facility also bearing Otto Schiff’s name, and £16 million to WJR.16 OSHA also distributed funds to AJR, Jewish Community Housing Association, and Jewish Blind and Disabled, which received more than £500,000 each,17 and money was granted to Jewish residential and nursing care programs, the Holocaust Centre, and a local Jewish center, too. According to Mitchell, thousands of people have benefited as a result of distributing OSHA’s profits. “Looking at some of the capital projects which we have helped to fund, I have no doubt that we could not have done these ourselves [nor could have] the organizations that we have helped and done a better job,” he said.

Creation of the Six Point Foundation

Additionally, £4.09 million created the Six Point Foundation.18 Named after the six points on the Star of David as well as the six million Jewish people killed during the Holocaust, the foundation offers two types of grants: individual grants and organizational grants. Individual grants are awarded to Holocaust survivors living in the United Kingdom for services that will enhance the quality of their lives. Individuals must go through a partner agency that requests the Six Point Foundation grant on their behalf. Many of these grants are small but meaningful. Examples include new computers, walk-in bathtubs, and travel expenses to visit family in the United States.19 These grants help support and better the lives of the people that OSHA once served. Short-term organizational grants are awarded to nonprofits in the United Kingdom that serve elderly Jewish people, to help support programs for Holocaust survivors. Organizational grants have been awarded to purchase a bus to transport elderly to social gatherings, operational costs to supply kosher meals to the elderly, and programming costs for a religious study group.20 Six Point describes itself as a spend-out, grantmaking foundation, meaning that it plans to close once it distributes all of its funds. Because of the foundation’s spend-out model, these grants are not intended to be recurring.

Since the Six Point Foundation’s establishment, it has received additional financial support from OSHA. As reported in the foundation’s 2013–14 financial statements, OSHA granted the foundation £1.675 million and an additional £1.2 million for a specific technology initiative.21 Additional funding is not guaranteed in the future, according to the foundation’s executive director Susan Cohen. This “bonus” funding was a result of the resolution of potential liabilities. OSHA previously earmarked funds for contingencies, such as pension liability for former employees, that have since been resolved and deemed unnecessary. Since OSHA no longer needs to hold these funds in reserve, it distributed them to the foundation.

Currently, the Six Point Foundation expects to cease its operations in March 2017. The foundation’s financial statements corroborate its trustees’ views on the spend-out model. According to Cohen, “Trustees reconfirmed their position that they did not wish to be held to a strict spend-down timeline but recognise, given the needs of the Foundation’s target group, that a further three to four years is a realistic timeframe.”22

Current State of the Otto Schiff Housing Association

While OSHA is no longer a direct-care provider, the organization still exists. OSHA’s 2013 financial statements show that it is still moving hundreds of thousands of pounds and earning interest from its investments. Because of OSHA’s responsibility to two regulatory agencies, the Charity Commission and the Housing Corporation, the organization has had legal issues when trying to merge the last of its assets with another charity.23

The organization has settled other major obligations, such as pension funds, but major obstacles remain. According to Mitchell, OSHA is “obliged to repay certain Social Housing Grants to the relevant government bodies. These can only be undertaken once an invoice has been raised by the [Housing Corporation]. However, obtaining this document has been equal to sucking blood from a stone.” Once this invoice is produced, OSHA will use its remaining funds to meet this obligation, in addition to covering other operating expenses such as annual audit costs and legal fees related to the closure. As Mitchell explained, while he hopes to have everything finalized by March 2015, “if it continues to be difficult to get this done, I will recommend to our trustees that we just close up.”

• • •

The Otto Schiff Housing Association has a rich history in the United Kingdom’s Jewish refugee community, and remains committed to providing care to hundreds of Holocaust survivors and Jewish refugees, even if it is no longer providing direct-care services. Thanks to the guidance and determination of Ashley Mitchell, the Otto Schiff Housing Association turned financial deterioration into an opportunity to provide major financial support to other Jewish care providers working with the same client population, or directly to individuals through the Six Point Foundation. As Mitchell settles the organization’s remaining financial obligations, the history of the Otto Schiff Housing Association is a powerful example of an organization’s dedication to its mission.

Notes

- Ronald Stent, “Jewish Refugee Organisations,” in Second Chance: Two Centuries of German-Speaking Jews in the United Kingdom, Werner E. Mosse et al, eds. (Tübingen, Germany: J. C. B. Mohr, 1991), 597.

- See Anthony Grenville, “Otto Schiff: In Defence,” AJR Journal 14, no. 6 (June 2014), 1–2.

- Stent, “Jewish Refugee Organisations,” 598.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time,” courtesy of Ashley Mitchell.

- Ibid.

- “The AJR in 1988: A Hive of Activity,” AJR Information 44, no. 5 (May 1989), 1.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- Kaye Wiggins, “Ashley Mitchell, Chair of the Otto Schiff Housing Association,” Third Sector, March 15, 2011, www.thirdsector.co.uk/ashley-mitchell-chair-otto-schiff-housing-association/governance/article/1059518 cde3.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- “How to Make £57 million in Sales,” Jewish Chronicle Online, March 3, 2011, accessed November 3, 2014, www.thejc.com/community/community-life/46105/how-make-%C2%A357-million-sales.

- This and all subsequent unreferenced quotes by Ashley Mitchell are from an interview with the authors.

- Wiggins, “Ashley Mitchell, Chair of the Otto Schiff Housing Association.”

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- “How to Make £57 million in Sales.”

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

- “UK Holocaust Charity in Sunset,” eJewish Philanthropy, March 1, 2011, accessed November 3, 2014, ejewishphilanthropy.com/uk-holocaust-charity-in-sunset/.

- “How to Make £57 million in Sales.”

- Six Point Foundation (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Report and Financial Statements for the Period 21 July 2011 to 31 March 2012, 2, accessed December 9, 2014, www.sixpointfoundation.org.uk/domains/sixpointfoundation.org.uk/local/media/downloads/six_point_foundation_trustees_annual _report_and_accounts_2011-12.pdf.

- Ibid.

- “Case Studies,” Six Point Foundation, accessed November 3, 2014, www.sixpointfoundation.org.uk/case-studies.

- Six Point Foundation (A Company Limited by Guarantee) Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 March 2014, 5, accessed November 4, 2014, www.sixpointfoundation.org.uk/domains/sixpointfoundation.org.uk/local/media/downloads/six_point_foundation_trustees_annual_report_and _accounts_2013-14.pdf.

- In an interview with Susan Cohen.

- Otto Schiff Housing Association, “A Brief History of Our Time.”

Katie Grivna is a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Sandi Toben is Host Sub-Committee Chair at the Spruce Foundation, Philadelphia, and a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania.

Curating Change: The Merger of the International Museum of Women and the Global Fund for Women

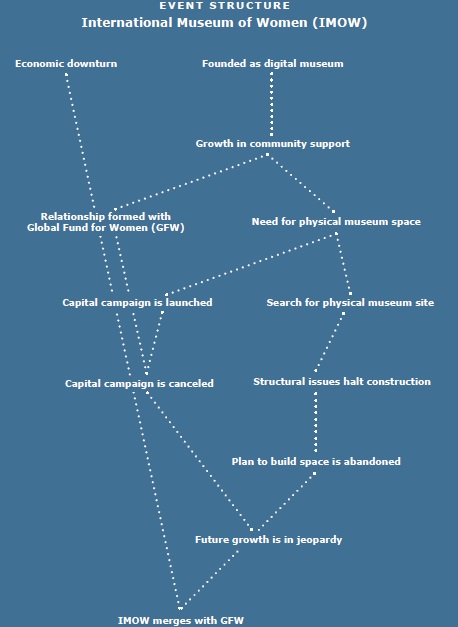

by Sarah Burke and Chloe Singer

This case study looks at the factors that led up to the International Museum of Women’s (IMOW) decision to merge with the Global Fund for Women (GFW) in March of 2014. While we reached out to previous IMOW staff—now at GFW—for a firsthand account of the events that led to the merger, we were unsuccessful and had to rely upon secondary information for evaluating the two organizations’ financial and strategic decision to merge their staffs, boards of directors, and operations under one shared mission.

The International Museum of Women

From 1985 to early 2014, the International Museum of Women operated as a digital museum, curating exhibitions, producing physical installations and events around the world, and developing an educational curriculum, all in aid of inspiring creativity, awareness, and action on vital issues for women. According to IMOW, approximately 70 percent of visitors surveyed reported changes in their opinions about global women’s issues, and up to 60 percent reported taking action toward gender equity as a result of engaging with IMOW’s digital content.1 But in March of 2014, the museum announced it was shutting down operations as an independent entity and merging with the Global Fund for Women, the largest public foundation in the world dedicated to advancing women’s and girls’ rights through an international network of women-led organizations, advisors, and supporters. But if IMOW was so successful in achieving its mission and advancing global gender equity, what events led to its decision to merge?

A Museum without Walls

IMOW was originally founded, in 1985, as the Women’s Heritage Museum, and for over ten years it operated as a “museum without walls,” producing exhibitions and resources for the public. Jeanne McDonnell, the museum’s executive director in 1995, articulated IMOW’s mission in the following statement: “We have been working for ten years in the field of public education in women’s history. We have not limited our subject boundaries geographically because we believe that women’s mutual concerns transcend political boundaries.”2

Growing support from the community led the museum’s board of directors to begin plans to create a single-destination women’s museum in San Francisco. In 1994, the museum submitted an application to build a physical space in the Presidio. The plan, which they titled “Shooting for the Stars (A Plan for the Women’s Heritage Museum at Presidio) 1995–2035,” was an ambitious one. The museum envisioned not only building the physical location in the Presidio but also simultaneously building a coalition of similar women’s museums in South America, Africa, China, Japan, and Eastern Europe—along with creating its own television channel, developing a series of educational programs and scholarships, and creating partnerships with other global cultural organizations. However, although its application to lease one of the Presidio buildings was initially approved, political changes derailed all nonprofit efforts to lease space there, and the museum was forced to move in another direction.3 Despite this setback, the board of directors stuck to its decision to look for a physical home for the museum. And, in 1997, the board decided to change the museum’s name from the Women’s Heritage Museum to the International Museum of Women, to reflect the museum’s focus on global women’s issues.

Following the Presidio project, the museum developed a $120 million campaign to build a 100,000-square-foot museum on Pier 39, in San Francisco, with a targeted opening date of 2008. The museum continued simultaneously to develop its global program, holding thirteen major exhibits focusing on such topics as women and political participation, global motherhood, and women’s role in the global economy.

In 2005, after the museum had invested nearly $1 million in site evaluation and raised cash and pledges of $7.5 million, site inspectors uncovered significant structural problems with the pier that would cost an additional $20 million to correct.4 The additional costs were too exorbitant, and the museum canceled its plans to build a physical museum and refocused on the original mission of running a “museum without walls.”

Partnership with the Global Fund for Women

That same year, IMOW began a relationship with GFW that would prove to be very fruitful for both organizations. With funding from a GFW grant, IMOW was able to produce a large-scale virtual exhibition, Imagining Ourselves: A Global Generation of Women. The exhibition included an intersection of film, photography, music, poetry, and personal essay—all responding to the question, “What defines your generation of women?”5 GFW promoted the exhibit to its stakeholders, allowing IMOW to tap into a much larger network and increase global exposure to the virtual exhibit. The result of their collaboration is an ongoing, interactive, multilingual exhibit that has thus far received over sixteen million visitors, and more than one million people representing 230 different countries have participated in producing content—personal stories dealing with war and peace, cultural conflict, motherhood, identity, and other experiences important to women globally.

The exhibit received worldwide attention and, in 2007, led to IMOW’s winning the Anita Borg Social Impact Award, which recognizes the accomplishments of women leading in technological innovation. As the institute expressed it at the time, “[IMOW] amplifies the voices of women worldwide through history, the arts and cultural programs and exhibits that educate, create dialogue, build community and inspire action. With its unique focus on cultural change, the Museum advances the human right to gender equity worldwide.”6 The success of the exhibition demonstrated to both entities the global impact that could be effected through strong partnership, and reinforced IMOW’s belief that a virtual museum was a relevant model for advancing its mission and engaging a global audience.

Financials

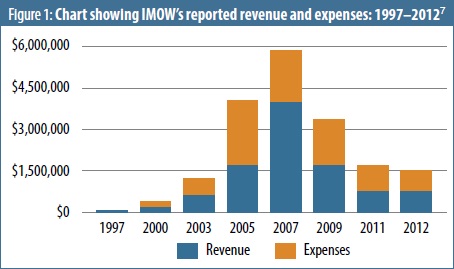

Just one year after the success of their exhibition and winning the Anita Borg Social Impact Award, however, IMOW’s financials began a downward spiral. A review of the museum’s Form 990s over the seventeen-year period of its filings, illustrated below (figure 1), tells the whole story.

While the museum was established as a 501(c)(3) in 1985, 1997 was the first year it was required to file a Form 990 with the IRS, at which time it reported zero expenses and a modest annual revenue of $31,890. By 2001, total revenue was at $641,658—a nearly 2,000 percent increase. Between 2003 and 2005, there was a large leap in expenses due to the undertaking of the capital campaign. Total expenses in 2005, the year IMOW announced the end of the campaign, came in at over $2.3 million, while total revenue was just under $1.6 million—a net loss of approximately $770,000.8 Between 2005 and 2011, expenses went down and revenue increased; and in 2007—the peak of its growth—IMOW brought in nearly $4 million in annual revenue, ending that fiscal year with a net gain of $2,116,579. The following year, however, revenue plummeted to $889,262, and the museum ended fiscal year 2008 with a net loss of more than $2 million. By 2013, the final year IMOW filed, it reported a total revenue of just $655,462—a dramatic decrease from just five years prior.

What was behind this downward spiral?

During the capital campaign, IMOW had “staffed up” and brought on a vice president of development, further adding to its overhead expenses. This employee was given a comparatively outsized annual salary of $155,000 (as a comparison, the vice president of education management and the vice president of marketing were paid $55,000 each, annually). Furthermore, the executive director’s compensation rose from $22,000 to $177,000 during this period, significantly adding to IMOW’s increase in total expenses.9

As the money from the capital campaign began to disappear, IMOW’s overall financial situation plummeted further. While IMOW’s official explanation was that the needed repairs to the pier had caused the project’s demise,10 a look into IMOW’s records by San José State University indicates that the campaign “ultimately failed due to lack of funding and the economic downturn.”11 By 2008, IMOW was operating at a total net loss of more than $2 million. Of its expenses, $2,030,486 was paid toward program services, while it received a mere $856,141 in contributions. Furthermore, in 2008, the museum’s CEO was paid $208,981, and two other employees, the vice president of development and the vice president of programs, were each paid $120,000.12 While not outlandish figures for a large international organization, it is problematic for the salaries of staff to rise while an organization is operating at an extreme loss.

By 2010, clear structural changes had been put into effect: the CEO was replaced, and there were major reductions in salaries and paid positions. By 2012, IMOW’s total revenue was just $757,920, and expenses were $714,929. The new executive director was given an annual salary of $117,000, and there was only one other paid position.13 It is clear from these numbers that, even though IMOW was staying afloat, it did not have the assets or staff to make the global impact it desired.

The Merger

Meanwhile, in contrast to IMOW’s shrinking numbers, GFW was—and remains—a true powerhouse in women’s rights advocacy: its 2012 revenue was over $18 million with expenses just under $15 million.14 GFW invests nearly $9 million each year in women-led organizations.15 Its efforts have helped to form women’s rights organizations, launch Women’s Funds, and provide more than $100 million dollars in grants to over 4,600 organizations in 175 countries.16 GFW’s extensive community and strong financial stability were a clear lifeline to the struggling IMOW, and IMOW’s commendable skills in digital storytelling promised to help accelerate GFW’s communications efforts. IMOW and GFW saw the opportunity to double their impact, reach new audiences, and get closer to achieving their shared vision: “a just, equitable, and sustainable world in which women and girls have resources, voice, choice, and opportunities to realize their human rights”17—and in March 2014, the two organizations merged under GFW’s name.

IMOW has only released positive publicity regarding the merger, but it necessitated considerable sacrifice. Not only did IMOW as a legal entity disappear, it also gave up its independence and ability to control its decisions and future. GFW’s CEO and president, Musimbi Kanyoro, continues to serve as CEO, while IMOW’s president became vice president of advocacy and innovation. In addition, due to GFW’s much larger size, the boards of each organization did not merge equally—GFW’s board took on just two members of IMOW’s board.18

IMOW’s merger with GFW was a selfless and strategic move to achieve its stated goals. Simply put, by combining forces with GFW, IMOW could be most effective.

Moving Forward

According to the Stanford Social Innovation Review, nonprofit mergers and acquisitions have dramatically increased over recent years:19 “Merged nonprofits can roll together annual audits, combine insurance programs, and consolidate staffs and boards. But they are also bigger and more complex and require more and better management—a cost that often exceeds the savings from combined operations.”20 It has been just nine months since IMOW and GFW merged, and it appears that the merger was a successful move that relieved IMOW of its financial struggles and helped to further both organizations’ global impact. Still, it will be interesting to see whether this merger allows IMOW to continue its mission within the GFW infrastructure, or if IMOW will struggle with the loss of its own unique identity and sense of autonomy.

Notes

- “About [the International Museum of Women],” International Museum of Women, accessed October 30, 2014, www.imow.org/about/.

- Ibid.

- Rachel Miller, Danelle Moon, and Anke Voss, “Seventy- Five Years of International Women’s Collecting: Legacies, Successes, Obstacles, and New Directions,” American Archivist 74, no. 506 (2011): 18, www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/AAOSv074-Session506.pdf.

- Sarah Duxbury, “Women’s Museum Pulls the Plug on $120M Pier Plan,” San Francisco Business Times, April 21, 2005, www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/stories/2005/04/25/story3.html?page=all.

- “What Defines Your Generation of Women?,” Imagining Ourselves: A Global Generation of Women, International Museum of Women, accessed November 9, 2014, imaginingourselves.imow.org/pb/Home.aspx.

- “Paula Goldman: 2007 Social Impact ABIE Award Winner,” Anita Borg Institute, accessed November 9, 2014, anitaborg.org/uncategorized/paula-goldman/.

- Adapted by the authors from “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” International Museum of Women, 1997–2012.

- “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” International Museum of Women, 1997–2012, accessed November 1, 2014, www.guidestar.org/organizations/77-0072401/international-museum-women.aspx#forms-docs. See also www.guidestar.org/organizations/77-007240/international-museum-women.aspx#forms-docsg.

- “Paula Goldman: 2007 Social Impact ABIE Award Winner,” Anita Borg Institute.

- Duxbury, “Women’s Museum Pulls the Plug on $120M Pier Plan.”

- San José State University, Guide to the Women’s Heritage Museum/International Museum of Women Records, MSS-2010-02-1818 (San José, CA: San José State University Library Special Collections & Archives, 2010), 3.

- “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” International Museum of Women, 1997–2012.

- Ibid.

- “Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax,” Global Fund for Women, 2012, accessed November 1, www.guidestar.org/organizations/77-0155782/global-fund-women.aspx#forms-docs.

- “Financial Highlights,” Global Fund for Women, accessed November 1, 2014, www.globalfundforwomen.org/who-we-are/financial-highlights.

- “25 Years of Impact,” Global Fund for Women, accessed November 1, 2014, www.globalfund forwomen.org/impact.

- “Merger FAQ,” Global Fund for Women, accessed October 30, 2014, www.globalfundforwomen.org/merger-faq.

- “Our Merger with Global Fund for Women,” International Museum of Women, accessed October 30, 2014, www.imow.org/about/merger.

- David La Piana, “Merging Wisely,” Stanford Social Innovation Review 8, no. 2 (Spring 2010).

- Ibid.

Sarah Burke is development manager at Soroptimist International of the Americas and a graduate student in the Nonprofit Leadership program in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Chloe Singer works for the Penn Fund and is a graduate student in the Penn School of Social Policy and Practice at the University of Pennsylvania.

Death or Reincarnation?

The Story of ACORN

by Emily Conners and Marissa Meyers

The story of ACORN illustrates how nonprofit organizations, like organizations in other sectors, are not infallible. ACORN’s downfall exemplifies what happens when a variety of factors are allowed to conspire to end an organization’s life. However, a more in-depth analysis of ACORN’s death exposes possible signs of life. Does ACORN’s legacy live on within the disaffiliated local branches? In other words, is ACORN truly dead, or is a reincarnation taking place?

Death

ACORN’s death occurred in 2010, when the organization filed for Chapter 7 liquidation. But the death of ACORN cannot be fully understood without looking at the organization’s history. Founded by Wade Rathke and Gary Delgado, ACORN began in 1970 as Arkansas Community Organizations for Reform Now (the organization later changed “Arkansas” to “Association of”). ACORN became a national and international network of community organizations, with an emphasis on advocating for low- and moderate-income families on social issues. During its lifetime, ACORN’s membership included 175,000 families in 850 chapters in seventy-five cities in the United States and abroad.1 But as the years progressed, the ACORN story revealed a plethora of ways in which to effectively kill an organization.