Across the United States, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives, programs, and offices are under attack, primarily by Republican state lawmakers and Republican governors. Measures targeting DEI have been passed and signed in Florida and North Dakota and have advanced in state legislatures across the country. A report by the Associated Press found that Republican lawmakers in a dozen states have advanced at least 30 bills similarly targeting DEI measures at colleges and universities.

Amid these legislative maneuvers, some leaders in higher education and DEI are speaking out with increasing alarm, and with calls to action. Among those leaders is Paulette Granberry Russell, president of the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

In a conversation with NPQ, Granberry Russell makes the case that these measures represent far more than symbolic political gestures—rather, she says, they threaten to reverse decades of progress towards more equitable and inclusive colleges and universities.

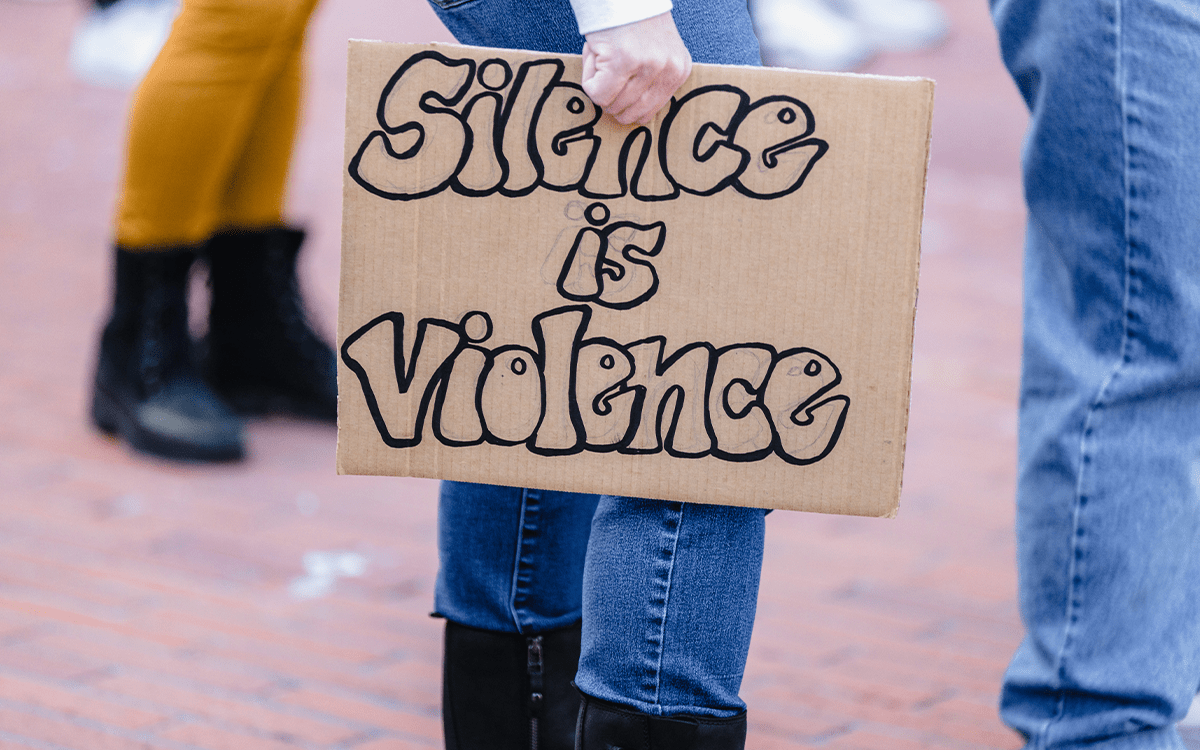

Granberry Russell not only elucidates the potential harm these measures can inflict on higher education but also calls out what she characterizes as a dangerous stifling and resulting silence among leaders in higher education whose responsibilities, she argues, include speaking out against anti-DEI efforts and making public the harm they carry.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

NPQ: I think there can be a tendency to view these attacks on DEI and related measures around the teaching of race and racial injustice as political messaging, rather than actual policy initiatives with real-world consequences. Can you describe the potential impact you see in cutting funding to DEI at colleges and universities?

Paulette Granberry Russell: Aside from disappointment, I see these efforts as really taking us back in time, quite honestly, given where we are today in higher education. And it is very difficult for those of us who are senior diversity officers or…diversity practitioners, scholars, researchers to be in a moment in time in twenty-first-century America, where for some it feels as though we are going back to the pre-Civil Rights era in this country. And some will offer that it feels like we’ve gone even further back to an era pre-Reconstruction. That’s for those who are even more pessimistic….Depending on the day that you catch me, I can be somewhat hopeful, given the fact that we know that there are some states where legislation has been introduced but has been either tabled or vetoed or not passed….But the fact that we have three [anti-DEI bills] that have been passed and signed…that’s where we are right now.

The fact [is] that we expanded the scope of, and protections based on, social identity. When I talk about social identities, I’m talking about race. I’m talking about gender. I’m talking about ethnicity, national origin. I’m talking about political ideology. I’m talking about veteran status. I’m talking about abilities. I’m talking about class.

“I see these [anti-DEI] efforts as really taking us back in time.”

But we cannot overlook the history of this country in the context of race and certainly gender and national origin and ethnicity, where there were laws that made discrimination lawful. And so for years, including throughout the Civil Rights movement and the signing of the Civil Rights Act in ‘64, we’ve been working to eliminate those barriers to opportunity that shouldn’t have existed in this country, except for the fact that there was resistance to justice and racial equity. We’ve got to start there, because this resistance has its roots in the origins of attempts to create a more equitable country.

If you start there and if we do not allow ourselves to be confused by what the clear targets are with respect to these efforts, [this resistance to DEI] focuses on race….It focuses on ethnicity. It focuses on gender identity. So, let’s be real clear.

All of the work that goes to address the lingering impact of past discrimination and addressing how we make those spaces a more equitable environment for those that have been historically marginalized, underrepresented, underserved….[These laws say that] you can’t do that work. That’s what’s lost.

The ability to create campus spaces and programs that address hostility; to examine policies and procedures to determine if they are leading to inequitable outcomes, whether it is how students are represented on our campus or how faculty themselves experience the campus environment; the outreach efforts that go into creating a more diverse student body, outreach efforts that go to creating a more diverse workforce, outreach efforts that ensure that we are reaching out and including more diverse vendors on our campus; those programs that support not only the legally-minimum ways of creating an accessible campus for our students; academic support programs or social support programs—those are all in jeopardy at this point.

NPQ: You’ve been vocal in calling out leadership in the field, including the leaders of higher educational institutions, for not speaking out more and more forcefully against these anti-DEI initiatives. How have the institutions being targeted fallen short in addressing the potential harm here?

PGR: This is all public information, so I don’t mind sharing this: 28 Florida College System presidents issued a joint statement in January of 2023 in support of the DeSantis [anti-DEI] policies. Then, when Inside Higher Ed asked 40 public college presidents in Florida to weigh in on state higher ed reform, none, even with anonymity, would speak. They’re frightened.

“Not enough leadership, especially in the private sector, have chosen to stand up and speak out.”

One of the impacts of this is the chilling effect that it’s having on leadership in higher ed. It’s not just in those states that are currently under attack…even those that are not currently subject to [such] legislation fear that they may become the next target for these efforts. And that’s a real fear. I think that’s a legitimate concern. But in the meantime, you can’t be silent while all of this is happening.

This is, I think, a universal concern, or at least it should be. And whether it’s within higher ed or outside higher ed, choosing to stay silent on this is frightening.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

You mentioned the [Association of American University Professors] coming out with their [report] and I’m grateful—it was overdue. I think that’s true also for The Ohio State University Board of Trustees [which] issued opposition to Senate Bill 83. I’m grateful that they’ve chosen to come out as strongly as they have. You have the American Council on Education and PEN America who’ve issued a report.

I’m gratified by that. But not enough leadership, especially in the private sector, have chosen to stand up and speak out.

NPQ: You think more leaders inside and outside of higher education should be speaking out more and more forcefully. What should the message be? Are there ways in which or reasons that message has failed to get through so far?

PGR: I think what this has pointed out to me, and this is a point that I have made in other spaces as well: I think we took a lot for granted, meaning that with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the progress that we’ve been making, and in the development of new programs and policies that were intended to…make real the values and the mission of higher education—somehow we were not prepared for this kind of backlash. What we perhaps failed in doing was taking for granted that this was work that was understood by the broader audiences out there.

We made a lot of assumptions that what was for us good work, work that was beginning to yield outcomes—not only increased diversity among our student bodies, but [in] our workforce and the research that was evolving—we failed to understand that what was yielding good outcomes was not necessarily by the standards of others good outcomes.

One of the things that [NADOHE] is working towards is helping a broader audience understand the actual realities of what it means to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion in higher education.

NPQ: As we’ve said, these policies will have, are already having, real impact on real people. What does the implementation of these policies actually look like on the ground?

PGR: Certainly, the more immediate impact is, for some, the possibility that they will no longer be employed…in work that they have developed over time, whether it was through their academic pursuits or their experiences and commitment to using evidence-based research to inform how they do work.

“Higher ed will not survive in the absence of being deliberate and intentional about creating inclusive, equitable campuses that are also diverse.”

And I have to explain this to people….This is a profession like any other profession. It is a discipline like any other discipline. The assumption that anyone can walk in and do this effectively is a myth….These are careers and these are lives that will be directly impacted.

And I know people will say we can do [DEI] differently, without giving attention to it. What does that mean? That these things just happen magically? As an organization, we are insisting that higher ed will not survive in the absence of being deliberate and intentional about creating inclusive, equitable campuses that are also diverse.

NPQ: You’re making the case that defunding DEI initiatives will have negative impacts that go far beyond individual faculty, staff, students, diversity offices—that without these initiatives higher ed “will not survive.” Can you say more?

PGR: It is not unlike if a university decided tomorrow that we’re going to eliminate our infrastructure around information systems. Now, some would say you can’t liken diversity, equity, and inclusion work to information systems and technology. We need technology.

Well, you know what? You need diversity in higher ed, okay?…And you need people who are skilled in understanding the role and impact of diversity in higher education. You need people who understand the need to create a space within [science, technology, engineering, and math] that welcomes all because we know as a country, until we expand who’s participating in graduating in STEM, we’re not going to be able to compete in the ways that this country needs to be able to compete.

So is it essential that this work be protected, that it be held up, that it be acknowledged, that we do not hide from these positions and try and situate them in spaces that really don’t give them the visibility because it makes them a target. There’s a point in time when if we are unable to defend our values and our mission, then why do we exist?

What’s happening right now is at the state level, but [these efforts] are very coordinated, as I think others have come to recognize. They have model legislation. And the legislation that’s being introduced is indeed modeled after the model legislation. Some have been less successful in some areas…but if they attack the work [of DEI] and they have a chilling effect on people speaking out, then they’ve been successful in silencing the voices of those that should be speaking out—especially if we think back on 2020, the racial reckoning and the statements that were being made not only in higher education, but throughout this country and in the public sector, in the private sector, in all the value statements and in the commitments.

But those voices are silent right now, and we need those voices as much today in ‘23 and ‘24 as we needed them in 2020. If you silence the voices, you can also silence the efforts. And that’s where I think we are right now.