July 1, 2015; Philanthropy Daily

The author of the insightful and vastly entertaining Great Philanthropic Mistakes, Martin Morse Wooster, writes in Philanthropy Daily about the problem of corruption in the delivery of aid to developing countries—and what grantmakers could and should do to prevent it.

Using an article by Patrick Radden Keefe in the New Yorker as a starting point, Wooster discusses a charity called Afghans for Civil Society, established in 2002 by former Christian Science Monitor and NPR reporter Sarah Chayes in collaboration with Qayum Karzai, the brother of the now-former Afghan president, Hamid Karzai.

Keefe referred to Qayum Karzai’s role as a “fixer,” which Wooster defines as “the guy who knows everyone and knows who has to be paid to get projects off the ground.” In this case, the fixer happened to be the sibling of the man in Kabul’s presidential palace who, backed by the U.S. military, could give the red light or green light to nearly anything in the country. Chayes, according to Keefe, was shocked by how much of her charity ended up as payoffs to “dubious people,” so by 2005, she quit the charity in favor of a soap factory called Arghand that employed Afghan women. Although she apparently tried to get assistance from USAID, which promised support for “indigenous enterprises,” Chayes found USAID frustrating and turned to some small foundation grants and the Canadian International Development Agency for more effective support.

Back on the subject of the charity, however, Chayes took aim at Afghan corruption and became an advisor to Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Admiral Mike Mullen on the topic. She was particularly critical of the web of corruption in the Afghan government and the Karzai family, calling corruption “a force multiplier for the enemy.” Was she surprised to discover that the U.S. military—and most of the world for that matter—knew of the Karzai family’s corruption but generally turned a blind eye because the focus was on prosecuting the war, not trying to clap the Karzai clan in irons?

Wooster’s brief essay warns that focusing on corruption could end up, in the hands of overly cautious grantmakers, as a reason to stop aid entirely:

“The great problem with trying to ensure the recipients of your grants are honest is that it gives another excuse for risk-averse program officers not to do anything. Of course aid should be cut off for people who abuse it. But that shouldn’t be an excuse for denying grants to groups that deserve them, particularly ones that don’t know foundation-speak.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

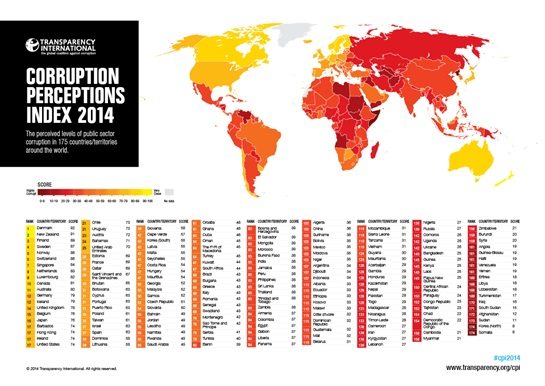

Wooster could have referenced the corruption ranking produced by Transparency International, which showed that among the most corrupt countries in the world are nations that have huge humanitarian aid needs and, not surprisingly, have been large recipients of assistance. The most corrupt nations in the world (according to TI) are, at the absolute bottom, Somalia and North Korea in a tie for the worst, followed by Sudan, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Iraq. Look at this map and you’ll see other nations where the humanitarian needs are great, such as Yemen, Eritrea, and others, but due to war and other turmoil, corruption is overwhelming:

So the answer is not to abandon the people in these countries due to the presence of “fixers” like Qayum Karzai. What should be done? Wooster suggests working through faith-based charities:

“I would also assume that private groups could do a better job in avoiding aid to criminals. In particular, it is probable that religious charities know people in the Third World who deserve aid and respect the principles of the Bible. I bet that World Vision and Samaritan’s Purse deal with more honest people than the Agency for International Development does.”

To some extent he may be right, particularly since, to their credit, some of these faith-based entities will go into settings that other charities avoid. However, he doesn’t take into account that many of these faith-based charities engaged in global humanitarian relief are part and parcel of USAID operations, recipients or intermediaries for USAID funding. Moreover, as Wooster knows, there is no guarantee that “faith-based” necessarily translates into “corruption-mitigating.” While there are excellent and credible faith-oriented groups close to the top of the USAID grant recipients list, it is difficult to ignore that atop that list is International Relief and Development, founded by religious folk, which had been USAID’s largest grant recipient in Iraq and recently was engaged in a battle against USAID’s suspension of the group as a grant recipient or contractor.

Wooster is certainly correct that “we shouldn’t use the problem of corruption as an excuse for institutional paralysis,” but the issue isn’t an either-or dynamic of either accepting corruption as unavoidable or getting out of the game (with a feint toward having private donors work through a couple of faith-based groups). Notwithstanding the choice of Chayes to move from building Afghan civil society to manufacturing soap, working to reduce corruption in global humanitarian aid is a worthwhile goal and can be pursued in the course of delivering assistance. Transparency International offers toolkits for businesses to counter bribery, for governments to negotiate “integrity pacts” (TI notes successful examples from Mexico and Pakistan), and for corruption-fighting individuals in NGOs and government. Perhaps Chayes was surprised to learn that the family of the president of Afghanistan could be so pervasively corrupt as the Karzais turned out to be, though for many people, that wasn’t a news headline. For those of us who have had to slog through corruption here in the states or overseas, the challenge isn’t to just to circumvent corruption, but to strengthen civil society to fight it.—Rick Cohen

Addendum: An earlier version of this article made reference to Mercy Corps as a “faith-oriented” nonprofit. Mercy Corps does not self-identify as faith-based.