Telling the story of U.S. public education requires more than Twitter’s 140 characters, but the problems are easy to identify. Many students are struggling, particularly those from low-income families, those with disabilities, those who do not have a command of English as a second language, and those who are children of color. National, state, and local policy debates have focused on strategies for improvement, but finding solutions that show proven results in the field is harder because the realities are so complex.

The Denver Public School district (DPS) teaches its 91,000 students in 200 schools that combine “traditional, innovation, magnet, charter and pathways schools.” Their student body is diverse: “Fifty-six percent of the school district’s enrollment is Hispanic, 23 percent is Caucasian and 14 percent is African American. […] 69 percent qualify for free and reduced-price lunches [FRL], an indicator of poverty.”

The strategy the district implemented over a period of years included many elements favored by school reform advocates. Now, we have the results of a recent study of the DPS system by Education Resource Strategies (ERS), funded by the Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation, to give us a deep assessment of a school district many see as a model of successful school reform.

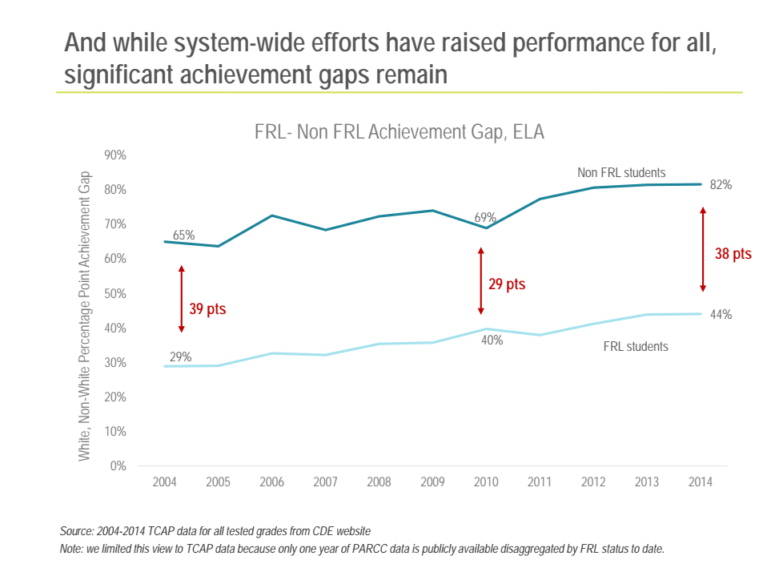

The ERS study, according to Chalkbeat, found that the “top-to-bottom efforts to reform Denver Public Schools are showing positive results, helping the district post the second highest rates of academic growth among large U.S. districts.” But while the district has improved overall, the “achievement gaps separating students living in poverty from their better-off peers has not been significantly reduced.”

ERS cited four system-wide characteristics as leading to improved effectiveness:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- The importance of creating effective system supports through a sustained and integrated redesign approach

- The power of a system-wide approach to human capital management…[to] attract, develop and retain high performing teachers and leaders

- The value of deliberate portfolio management that has avoided the unplanned under-enrollment and performance degradation in district schools that too often accompanies charter growth

- Translating strong enabling conditions into school-level changes in practice and resource

In many urban districts, willy-nilly expansion of charters has left traditional public schools underpopulated and under-resourced, causing harm to the students and to communities as a whole. At a time when portfolio management and school choice are high on the agenda of many reform advocates and policymakers, it’s important that Denver has effectively managed public “schools with different governance structures.” This is possible in Denver because the district is also the chartering authority for charter schools that serve its students. Other states where chartering is not seen as the function of the local school district might do well to study these results as they adopt new policies.

The Denver Public Schools’ strategy has also included the closure of schools that continually fall short of performance goals, replacing them with charter schools. The ERS study cautions the district to temper its aggressive approach to school replacement, a warning other districts should heed as well. Karen Baroody, managing director of ERS, told Chalkbeat:

Considerable effort should be invested in helping struggling schools. In reality, you don’t want to keep closing and opening schools. It’s like hiring a teacher and saying if they’re great, great, and if they aren’t, fire them. But brand-new teachers need help and support to get better and most schools, if given the right support, will get better.

On another important front, Denver still has a ways to go. Economic and racial integration is important, as integrated schools have both educational and civic benefits for all students. On this measure, Denver’s schools’ current reform strategies are not proving successful. ERS urged Denver public schools to “strategically place ‘proven models and operators’ of schools and adopt policies “that encourage integration in gentrifying neighborhoods.” Creating those policies is a challenge many school districts face, as housing patterns reflect an increasing separation of rich from poor and whites from people of color. Here, Denver may want to learn from Louisville, Kentucky, where there has been success in integration.

The successes Denver has achieved have not come without controversy. The district’s highly centralized management structure has raised questions of just how democratic and community-based the decision-making process is. In a deep look at the Denver system, Jeff Bryant, writing for AlterNet, concluded, “What Denver parents seem to want most from education policy in their community is for leaders to find a different way to talk about these issues, and to solicit, and honor, parent input before decisions are made.”

Denver’s successes are impressive, but they do not point to a primrose path to overcoming the effects of poverty and racial segregation on children. That lesson may be the most important one that this study of the Denver experience has to teach us.—Martin Levine