September 12, 2018; Twin Cities Pioneer Press

“From 2000 to 2014, Minnesota issued $1.4 billion in TIF (Tax Increment Financing) loans and financial obligations, making the state the fourth biggest user of TIF in the United States,” writes Frederick Melo in the Twin Cities Pioneer Press.

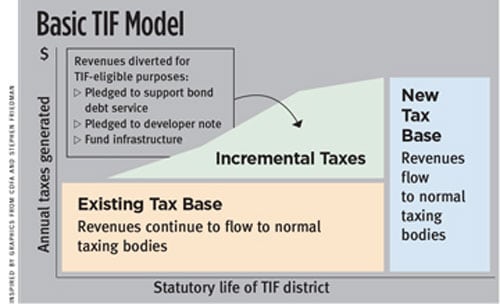

NPQ has covered TIFs before. As we wrote this past February, “TIFs are a method of financing development by borrowing against the anticipated benefits of economic growth.” They do this by diverting a portion of taxes in a designated zone to help finance development. The way this works is you set a baseline property tax rate where a city anticipates future development, then borrow against anticipated increases in property tax to fund the development for a specified period of time—say, 15 years. TIFs are often a leading vehicle to subsidize corporations.

Of course, borrowing is not cost-free—if the growth doesn’t occur, then the city must cover the loans with other revenues. And, if the growth does occur, then the city can pay back the loans, but schools and other public amenities may lack resources because growth outpaces resources and the money that would have funded those services is instead paying back the loans.

In a new 72-page report from the nonprofit Lincoln Institute on Land Policy, called Improving Tax Increment Financing (TIF) for Economic Development, University of Illinois at Chicago economist David Merriman notes that this dynamic sometimes “may result in higher taxes or lower services elsewhere, depending on how overlying governments, such as school and special districts, respond.”

But is tax increment financing worth these aches and pains? Not often, Merriman contends. Reviewing 30 studies, Merriman finds “in most cases, TIF has not accomplished the goal of promoting economic development.”

Merriman elaborates:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Many recent findings show that TIF does little to deliver economic growth and sometimes simply relocates economic activity that would have occurred elsewhere without TIF…communities should use it cautiously to avoid unintended consequences, such as diverting increased property tax revenues from counties, school districts, and other overlying governments; obscuring government financial records; and facilitating unproductive fiscal competition between neighboring jurisdictions.

Merriman notes that California, the first state to make heavy use of TIFs, now permits TIFs under very limited conditions, namely:

- TIF districts are restricted to low-income or high-crime areas;

- school entities are prohibited from participating;

- other overlying governments (non-school) must consent to use their tax revenues for the TIF;

- extensive reporting and transparency provisions are required;

- extensive public input is required, including provisions under which a popular vote could prevent further action on the plan;

- twenty-five percent of property tax increment revenues must be used to increase, improve, and preserve affordable housing; and

- issuance of bonds by TIF districts now requires 55 percent voter approval.

In his report, Merriman urges states to employ California-like provisions to better track TIF use. Merriman also writes that before a TIF district is created, states should “require proof that the planned development would not occur ‘but for’ the tax increment financing.”

TIF success stories, Merriman notes, do exist. Merriman provides case studies from Atlanta, rural Montana, and St. Louis. In St. Louis, a $158.2-million, 25-year TIF helped push forward a $2-billion project on city’s west side known as Cortex, which has led to a new economic hub. But St. Louis has had over 100 TIFs and most have fallen short. One reason, Merriman suggests, why Cortex has done better than many other TIF-funded projects is because the project did not rely on the TIF, but instead used the money from the TIF to generate lasting community partnerships.

Earlier this year in an op-ed, Melo noted that the attraction of TIF is that “cities and economic-development authorities don’t have to come up with their own tax dollars up front to acquire blighted land, demolish abandoned gas stations,” and so on. But there’s a cost: “For upward of 20 years, funds generated…don’t go to the city to fix your potholes or pay librarians or firefighters or cops” (or schools or other government programs that fund nonprofits). In St. Paul, Minnesota, nine percent of city property tax is diverted this way.

It is, Melo adds, a little like if you or I said to the local government, “Instead of paying you guys my property tax increase, can I use that money to clean the asbestos out of my attic?”—Steve Dubb