An increasingly popular view in the nonprofit sector is that nonprofits fail to adequately invest in advertising because of donor pressure to limit overhead. The growing popularity of this view is due in part to Dan Pallotta’s viral TED Talk, The Way We Think About Charity is Dead Wrong, as well as recent books by Dan Pallotta and Ken Stern. The implication of this view is that if nonprofits were unshackled from the obsession with accounting overhead, they would boost advertising and finally be able to grow the sector. While this view might have instinctual appeal, I worry that it lacks empirical support. In particular, there is no clear evidence either that nonprofits underinvest in advertising or that the desire to keep overhead low discourages such advertising.

Are nonprofits underinvesting in advertising?

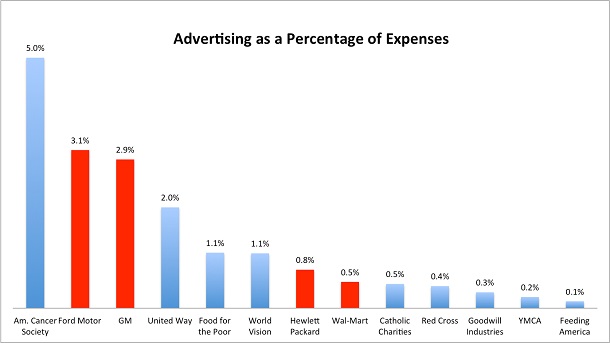

At the heart of the argument for greater nonprofit advertising is that for-profit organizations see the growth potential that advertising brings and, as a result, are far more willing to invest in it. Though we may feel that for-profits are much more aggressive advertisers, is that actually the case? After all, since the nonprofit sector is much smaller than the for-profit sector, it may just seem like the advertising footprint of nonprofits is smaller, when in actuality their relative behavior is quite similar. For illustration, consider the advertising expenditures of the ten largest US nonprofits (as ranked by Forbes) and the ten largest US for-profits (as ranked by Fortune). The data for nonprofit advertising is readily available from each organization’s most recent Form 990 filing (only the Salvation Army is excluded since it does not file a Form 990); the associated for-profit data can be found in their most recent 10-K filings. The first thing to note is that among the ten largest for-profits, only four view their advertising expenses as material enough to warrant separate disclosure. More importantly, among the remaining for-profit companies, advertising as a percentage of expenses is not noticeably different from that of their nonprofit counterparts, as seen in the next chart.

A glance at the chart reveals that advertising among the nonprofits is not appreciably smaller than that of the for-profits. This is made even more cogent by noting (i) the six for-profits with presumably smaller advertising are excluded; and (ii) the advertising figure for nonprofits reflects only Part IX, Line 12 of their Form 990 and excludes related costs of printing and postage that can also be substantial, given the prevalence of direct mail efforts. These caveats aside, the (equal-weighted) average advertising percentage among the nonprofits is 1.2 percent, whereas it is 1.8 percent among the for-profits. This is hardly a noteworthy difference.

Furthermore, when it comes to advertising, some nonprofits are leading the way. Consider, for example, the Wounded Warrior Project, a popular and growing veterans’ charity. From its most recent audited financial statements, advertising and promotions represented over 35 percent of total expenses. Such a high percentage of expenses devoted to advertising is unheard of in for-profit companies, which simply cannot both compete on price and make a profit while carrying such high advertising costs. Yet, it barely registers with donors of the Wounded Warrior Project, who continue to flood the organization with cash.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Are nonprofits punished for investing in advertising?

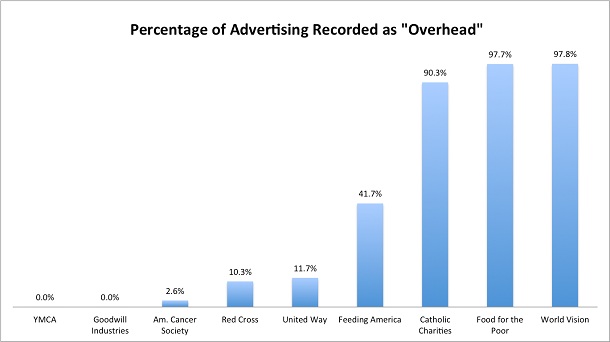

The second key feature of the argument to unleash more nonprofit advertising is that the reason advertising is currently limited is an unproductive obsession with reducing accounting overhead. The idea is that accounting rules treat all expenses incurred by nonprofits as either program-related or overhead (fundraising and administrative), and many donors and watchdogs fixate on what percentage of expenses are program vs. overhead. Setting aside the question of whether donors pay enough attention to such figures, the presumption by many is that advertising is automatically classified as overhead, so nonprofits are excessively discouraged from undertaking it. The problem with this presumption is that it is not how the accounting rules are typically applied. If an organization’s mission includes a stated desire to raise awareness about an issue or otherwise educate the public, associated costs are classified as program expenses, not overhead. Further, if a nonprofit undertakes an activity that includes both an awareness/education and a fundraising component, they are permitted to allocate the associated costs between fundraising and programs (and have substantial leeway in doing so). In other words, the presumption that advertising is treated as overhead is not correct. For each of the largest nonprofits discussed previously, the next chart shows what percentage of their advertising costs are actually classified as overhead.

As can be seen in the chart, only three of the nine organizations treat the majority of their advertising as overhead. More than half of the organizations treat less than 15 percent of their advertising as overhead. For those organizations, if advertising were their only expense, their program spending ratios would be greater than 85 percent—an excellent figure by any standard. Once again, this phenomenon is not unique to the largest charities. The example of the Wounded Warrior Project is instructive. Among its over $49 million in advertising and promotional expenses, only 1 percent is treated as overhead; the rest is considered program spending. That is, advertising expenses are actually what boosts their program spending ratio above 80 percent. This is hardly a circumstance of overhead ratios forcing a nonprofit to cut advertising.

Taking these points together, the message is not that nonprofits cannot benefit from more advertising—perhaps they can. Rather, the point is that there is limited evidence supporting the view that excessive scrutiny of accounting numbers is serving to undermine nonprofit growth. If anything, the degree of accounting flexibility provided to nonprofits and the reluctance for donors to look beyond simple summary figures and examine the details means that there is a false sense of scrutiny placed on nonprofits’ financial decisions.—Brian Mittendorf