October 19, 2016; New York Times

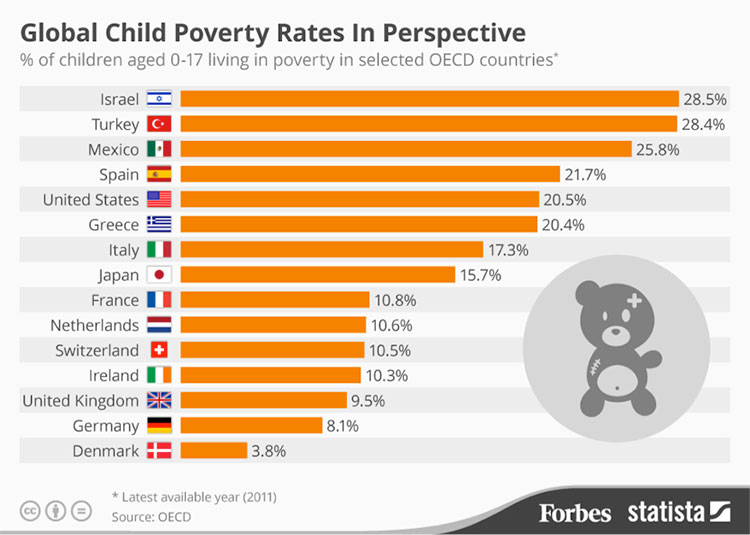

The United States leads the world in many ways in which we can take pride, but leading most of the industrialized world in child poverty brings shame.

This statistic translates into more than 14.5 million young people starting their lives at the bottom of a very steep hill. While this number has shown some improvement as the overall economy has recovered from the depths of the 2007 recession, it remains at a disturbingly high level.

Efforts to directly alleviate the pain of growing up poor have missed their target. Eduard Barros, writing in the New York Times, recently wrote,

The child tax deduction—which allows families to exclude $4,000 a child from their taxable income—avoids the poor almost entirely. Just over 1 percent of the $40 billion it costs the federal budget every year flows to the poorest fifth of the population….The $58 billion child tax credit that reduces a tax bill by $1,000 a child is more progressive. But families in the bottom fifth get only a tenth of the money.

This is a safety net that will let the poorest easily slip through.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Perhaps it’s time to consider a different approach, one backed by nine experts on poverty and child well being and that received support from pundits as diverse as Daniel P. Moynihan and Milton Friedman. Rather than the current system of tax credits and deductions, they propose providing every child with a monthly stipend of $250.

The benefit would be universal, like Social Security, rather than aimed at low-income families alone. And it would decouple government assistance from work, a sharp departure from the track followed since the welfare reform of the 1990s, when cash assistance was replaced with tax credits.

At the level being proposed, $3000/year, child poverty would not be eliminated but millions of children’s lives will be improved. It ensures that the poorest of children are not left out. This new approach is estimated to cost about $190 billion annually, less than twice the cost of the current program of credits and deductions. When compared to other countries using similar approaches, it does not seem extravagant.

Austria, Britain, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden all already have some sort of child allowance. In Germany, the benefit for a family with two children adds up to $5600 a year. In Canada, it is worth $4935 per child under 6, and $4164 for children ages 6 to 17.

As a universal benefit, it eliminates the stigma associated with need-tested programs. Because it does not require demonstrating one’s poverty, it would reduce the need for a large government bureaucracy to manage the program. And it would take the welfare of our children away from the ongoing political arguments over work that have marked decades of “welfare reform” efforts.

Creating a new universal benefit would not be easy in our current political environment. It asks that easing the pain of children be placed above political ideology. It asks us to be willing to critically think about what has worked and what has not in earlier efforts. These are clearly not easy challenges. However, 14.5 million impoverished children should be enough cause for politicians right, left, and center to seriously grapple with this moral imperative and end our global shame.—Martin Levine