Portions adapted from Tackling Equity, Diversity and Inclusion in Highly Matrixed Organizations, Deeohn Ferris, JD, June 7, 2019.

Equity, diversity, and inclusion is the topic du jour across disciplines and sectors. Writ large, these themes pertain to increasing the access and power of people and population groups who have been treated unfairly—that is, historically excluded, treated differently, or discriminated against. In addition to obvious social justice concerns, motivating these efforts are major demographic shifts occurring in the US, as well as studies that show improved performance, innovation, and profitability benefits for organizations that look like America.

Data on social and economic determinants put people of color on the forefront of the demand for fairness. However, people of different identities, cultures, faiths, ages, and abilities all grapple with different treatment. Performance, innovation, and profitability are pillars of the business case for diversity. Equity or fairness for all is a big test requiring decision-makers to look at their leaders, workers, partners, communities, and the customers they serve.

Leading environmental and conservation nonprofits are no exception. Notably, in 2014, Dr. Dorceta Taylor’s research team at the University of Michigan produced a groundbreaking report on the lack of diversity in the US environmental nonprofit sector. Among her findings: the percentage of people of color on boards surveyed was 4.6 percent; in sum, 1,607 of 1,684 surveyed board members were white. Staff were also shown to be heavily—about 88 percent—white. Similar to government and the private sector, but perhaps with even greater intensity, the future and vitality of environmental and conservation nonprofits depends on applying an equity lens to management systems and processes, and to investing in culture change that supports diversity and inclusion. This is no mean feat.

The largest green groups are hefty with structures, executives, middle managers, and supervisors. The biggest are major employers, with specialized staff, members, federated grassroots chapters and affiliates, supported by a vast array of consultants, vendors, and suppliers. They are a crisscross of business operations that include science, land stewardship, litigation, marketing, public education, local conservation, and policy advocacy.

Generally, although they are not exhaustive, organization development that tackles equity, diversity, and inclusion in the environmental nonprofit sector clusters into one or more of the following three spheres.

- Sphere #1 – The mission, scientific research, data, and language are accessible and relatable for women and people of color, and people from different ethnicities, faiths, cultures, and abilities.

- Sphere #2 – The workplace and contracting are fair, leaders and staff are racially and culturally diverse, and inclusion is the rule in recruiting, hiring, talent retention, professional development, and promotions.

- Sphere #3 – External partnerships and community engagement are respectful, reciprocal, and racially and culturally diverse audiences and advocates are involved and support the work.

Changing systems and culture in ways that value and respect marginalized groups is a journey. Making progress requires continuous attention, investment, and measurement.

Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Barriers

Historical context is important to organization capacity and skills that help surmount the biases, stereotypes, and legal and policy barriers that hinder inclusion of people of color and different cultures in environmental and conservation organizations. Race is important to this conversation because it is the biggest nonprofit equity, diversity, and inclusion bugaboo.

Typical barriers involve unequal status and rights, privileges, and benefits produced by social, political, and economic systems and institutions, and biases that prejudice in favor of or against a person or group. Bias is bad behavior usually attributed to implicit or unconscious thinking. Bias also happens when attitudes and stereotypes become the belief system, robbing people of their humanity and dignity.

People from many walks of life experience discrimination. K–12 funding fixes things so that richer, mostly white children will benefit from a disproportionate amount of the education resources for the next generation. Women in the workplace are denied promotions or paid less than men for the same or similar work. The military bars the service of transgender people.

Understanding what the barriers are and the ways they tie to an organization’s operations and decisions is the starting point to broadening awareness about the pernicious effects of inequity. This knowledge facilitates diversity and inclusion by setting the stage for deeper working relationships, learning from each other, and expanding social and professional networks.

Essential Definitions

Equity, diversity and inclusion are more than buzzwords and boxes to check.

- Equity is that addresses the differences in the actions, decisions, and investments that disadvantage one individual or group in favor of another. Equity involves bringing together and harnessing diverse forces and resources in ways that are beneficial for disadvantaged people and groups. Ultimately, equity is beneficial for all.

- Diversity means difference in many ways—race, identity, social roles, language, education, skills, and income, for a few examples. Usually, diversity is overhyped while inclusion is underemphasized. Nonetheless, diversity’s import is acknowledging the visible and invisible differences between us based on privileges and disadvantages.

- Inclusion puts the concept and practice of diversity into action by creating a welcoming environment of respect and connection. Inclusion corrals the richness of ideas, backgrounds, and perspectives to create organizational or business value. It is indispensable to valuing and retaining racially and culturally diverse people.

According to the Macmillan Dictionary, inclusion functions from “the belief that all people should feel that they are included in society, even if they lack some advantages.” Equity and inclusion strategies are the means to level the playing field. Organizations will not retain diverse talent or sustain authentic relations with diverse external partners until their culture bends—like Dr. Martin King Jr.’s arc of justice—toward inclusion.

Big Green’s Progress

Big Green organizations are tackling the challenges in different ways. Equity, diversity, and inclusion efforts vary, ranging from aspirational statements, creating leadership positions, and maintaining data on staffing, to recruiting and hiring practices, training young conservation leaders, and partnerships with environmental justice communities.

Green groups are chipping away at culture change by hiring chief diversity and inclusion officers, vice presidents, and directors to inform and lead their efforts. Many of them are leaders of color tasked with advising and devising internal plans, policies, and programs that promote shifts in organizational behaviors and amplify engagement with diverse organizations and communities.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Ascertaining demographic data is another starting point for transparency and changing Big Green’s business systems and processes. Groups are reporting demographic statistics for boards, staff, and senior staff using GuideStar USA Inc.’s publicly available Nonprofit Profile Tool. GuideStar, which recently merged with The Foundation Center to form Candid, is one of the first central sources of information on US nonprofits. It collects and reports data for gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disability status.

Environmental education is a diversity sweet spot for Big Green. Mainly, they are hands-on internships and fellowships for high school, college, and graduate school students aimed at attracting young people from different races and cultures—and growing a diverse new generation of leaders. Internships and fellowships exhibit a variety of green occupational opportunities and upwardly mobile career pathways. These programs are pipelines for next generation professional development and recruiting future employees.

Apprenticeships in the green nonprofit sector are a recent innovation for developing and recruiting young professionals who are early in their careers or enrolled in law or graduate school. The program at Audubon, where I work, dovetails on-the-job training and learning opportunities for young people who are interested in pursuing a career in the environmental and conservation field. Mentors guide the apprentices while they are serving in positions that advance organizational functions such as science, fundraising, marketing, outreach, communications, and finance.

Internal working groups, steering committees, affinity groups and employee resource groups are also advancing organization change. Linking people who share common purpose, ideology, or interest, they are helping to create a culture of belonging, safe spaces, and going the extra mile to support and welcome the contributions and experiences of everyone. Participants are expanding social and professional interactions and strengthening networks that will help attract diverse talent and engage more communities.

Changing language is part of the change equation too. For example, Audubon recently announced the terminology change from “citizen science” to “community science,” reflecting a more communal approach to caring for the environment. The word “citizen” originally distinguished amateur data collectors from professional scientists. However, the group recognized that the association with citizenship limited volunteerism, engagement in conservation work, and grassroots partnerships.

Externally, some of the biggest groups are opening doors to broader relationships by agreeing to implement the Jemez Principles for democratic organizing launched by the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice. They originated in 1996 in Jemez, New Mexico during the Southwest Network’s “Working Group Meeting on Globalization and Trade.”

The Jemez principles articulate a framework for respect, common understandings, and directives about organizing, reciprocity, inclusion and conduct between signatories from different cultures, politics and organizations. Jemez alliances exemplify the potential for synergies and gains between environmental organizations led by people of color and Big Green.

What’s Next for Big Green?

Green 2.0 is a non-governmental group that critically researches and monitors board and staff diversity. Their most recent report, Leaking Talent: How People of Color are Pushed Out of Environmental Organizations, shines light on the data and the disaffecting experiences of staff of color currently or formerly working for environmental NGOs and foundations. The report shows the need for leveling the playing field and deeper investments supporting multiracial and multicultural equity and inclusion.

The business imperative for equity, diversity, and inclusion is a moral story—and more than a moral story. Now more than ever, the planet needs a movement that appeals to and benefits all Americans. The implications of inclusion, nationally and globally, make that conclusion indelible. Building durable public will, strengthening civic participation that involves everyone, and diversifying the boots on the ground must be top priorities.

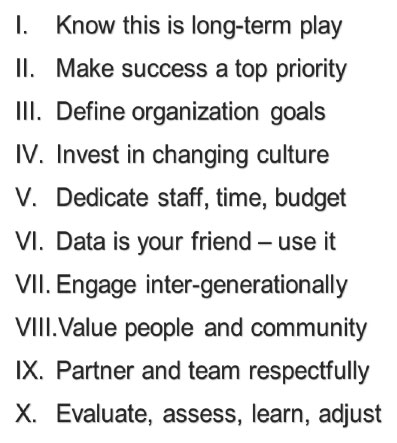

Culture change, however, is much more complicated than a policy campaign. Transforming complex organizations involves changing systems, processes, and behaviors tied to the discrimination facing certain groups. Below, I outline what I have found to be ten best practices for reshaping an organization’s cultural ethos. Culture change will happen when investments are commensurate with organization development and commit the financial, human, intellectual, technology, data, and training resources needed to move the needle.

People of color and young people on the forefront of climate change and environmental impacts in their neighborhoods support and vote in favor of pollution controls and climate change interventions by government. Beyond the moral imperative of engaging those at the margins who are most affected by environmental injustice, failing to engage these core constituencies is, simply put, strategically very foolish.

Big Green’s resiliency and vitality, now and in the future, hinges on culture change that incentivizes racially and culturally inclusive boards, executives and staff, and broadens the engagement in the mission of communities and people from all walks of life. While the sector is making progress, there is a lot more work to do.

The good news is—with intentionality and investment—we can get this job done together. The future of the planet depends on it.

References

- “Racial Equity Resource Guide.” April 2014. W K Kellogg Foundation.

- Sherbin, L., Rouse, R.R., February 1, 2017. “Diversity Doesn’t Stick Without Inclusion.” Harvard Business Review. Reprint H03FC8.

- Rouse, S.M., Ross, A.D., The Politics of Millennials: Political Beliefs and Policy Preferences of America’s Most Diverse Generation. University of Michigan Press (2018)

- Dishman, L., May 18, 2015. “New Rules of Work: Millennials Have a Different Definition of Diversity and Inclusion.”

- Clark, L.P, Millett, D.B, Marshall, J.D., September 14, 2017. “Changes in Transportation-Related Air Pollution Exposures by Race-Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status: Outdoor Nitrogen Dioxide in the United States in 2000 and 2010,” Environmental Health Perspectives.

- Mikati, I, Benson, A. F., Luben, T.J., Sacks, J.D., Richmond-Bryant, J., 2018. “Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status,” American Journal of Public Health. 108, 480_485

- Lee Staples (2012) “Community Organizing for Social Justice: Grassroots Groups for Power, Social Work with Groups”, 35:3, 287-296, DOI: 10.1080/01609513.2012.656233

- Lee, B, Jones, V., June 22, 2015. “Want to Win the Climate Fight? Engage Communities of Color,” Green for All.

- McElwee, S., Ray, J., February 7, 2019. “Young People Really, Really Want a Green New Deal,” The Nation.

- “Survey of Young Americans’ Attitudes toward Politics and Public Service,” Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics. 37th Edition: March 8 – March 20, 2019.

- Wolf, E.A., Hums, M., “Nothing About Us Without Us—Mantra for a Movement,” September 6, 2017. HuffPost.

- Pearson, A.R., Schuldt, J.P., “Facing the Diversity Crisis in Climate Change,” Nature Climate Change. Volume 4, December 2014.

- “Thomson Reuters Launches D&I Index – Reveals Top 100 Most Diverse & Inclusive Organizations Globally,” September 16, 2016.

- Hunt, V, Prince, S., Dixon-Fyle, S., Yee, L. January 2018. “Delivering Through Diversity,” McKinsey & Company.