January 6, 2015; St. Louis Public Radio

The American Civil Liberties Union has filed a federal lawsuit against St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCulloch on behalf of a grand juror in Darren Wilson’s case, alleging the prosecutor mischaracterized grand jury proceedings to the public. Similar allegations are being made in a bar complaint by a coalition of Missouri lawyers and citizens, alleging prosecutorial misconduct occurred in the case by McCulloch and two assistant prosecutors.

In the thirteen-page ACLU complaint, the plaintiff referred to only as “Grand Juror Doe” claimed several issues with the “muddled and untimely manner” the law was presented to the jury and that the records of the case released to the public do not properly reflect the proceedings.

Specifically, the grand juror took issue with McCulloch’s overgeneralized statement that “all grand jurors believed there was no support for any charges.” According to the lawsuit, “From [Grand Juror Doe’s] perspective, although the release of a large number of records provides an appearance of transparency, with heavy redactions and the absence of context, those records do not fully portray the proceedings before the grand jury.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The bar complaint includes similar allegations as the lawsuit, including that McCulloch knowingly allowed witnesses that he knew (or could reasonably assume) were lying to testify and that he presented the case haphazardly, without specifying charges.

Usually, grand jurors are not permitted to speak about the case on which they preside, nor is evidence presented during the case revealed to the public. Indeed, there are sanctions in place for jurors that violate this rule and discuss the case publically, which the ACLU lawsuit seeks to redress. Then again, Wilson’s case deviated from a typical grand jury hearing on several accounts, such as the release of the documents from the proceedings and McCulloch’s remarks to the press and public following the non-indictment.

Recognizing the particular circumstances of this case, the ACLU says the usual secrecy the grand jury is afforded must be bypassed, as permitting the juror to speak about his experiences of this case would be in the public’s interest:

“Plaintiff also wishes to express opinions about: whether the release of records has truly provided transparency. Plaintiff’s impression that evidence was presented differently than in other cases, with the insinuation that Brown, not Wilson, was the wrongdoer; and questions about whether the grand jury was clearly counseled on the law.”

Through discussing the case, the public could also learn about the inner workings of a grand jury and whether these proceedings are fulfilling their original purpose: operating as an extra layer of oversight that allows citizens to impede an unjust prosecution. Or have grand juries become pawns to advance prosecutors’ agendas? The argument to allow the juror to speak is even more compelling considering the additional and corroborating allegations of misconduct.

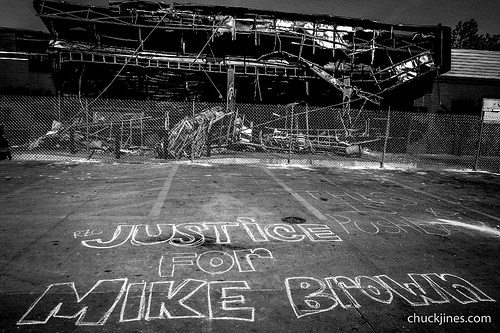

Therefore, determining whether the system of grand juries as employed in this case is malfunctioning would be a pertinent question to pose to the public, and the juror’s thoughts as an insider of that system would help facilitate that conversation. As more and more voices come forward calling to revaluate the handling of the Ferguson grand jury, a comprehensive evaluation can ensure further miscarriages of justices are not permitted.—Shafaq Hasan