July 7, 2017; USA Today

The March of Dimes has been the source of much commentary over the decades about the institutional will of organizations to survive their own original missions. In light of that, the public announcement of the sale of its headquarters, coupled with its declining finances, will be an interesting next chapter.

After running a deficit for the past five years, the 79-year-old March of Dimes has put its national headquarters on the market. Its Form 990 for 2015 lists an operating deficit of almost $27 million on an expense budget of $214 million. It is interesting to note on its 990 returns that the organization consistently outspent what it brought in by millions in each of the past five years. This year, it listed its fund balance as a negative $12 million.

Its statements, of course, do not reveal any particular organizational angst. “After careful evaluation of our office in White Plains, the March of Dimes building at 1275 Mamaroneck Avenue has been placed for sale on the real estate market,” writes Michele Kling, director of media relations for the nonprofit. She added that many of the nonprofit’s employees “have embraced a virtual working model.” (Very virtual in some cases, since the organization also recently laid off 100 employees.)

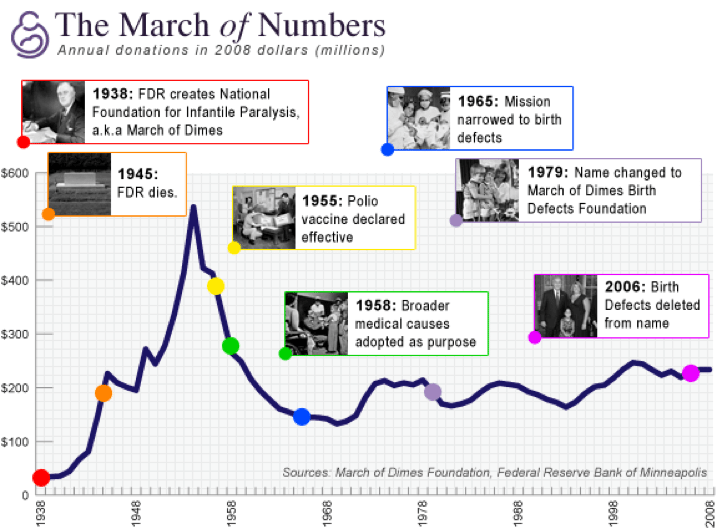

This is, of course, one of a number of inflection points for the organization, founded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1938 as the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. That organization faced questions about its own relevance and considered potentially disbanding altogether after polio was largely eliminated in the 1950s. In the end, it decided to continue with a new name—or a few new names, as William Barrett wrote in Forbes in 2008.

After a five-year internal debate that weighed adopting specific causes such as mental illness and arthritis, the charity in 1958 said—at a nationally broadcast press conference, no less—it would embrace a laundry list of medical needs, including birth defects. It also shortened its official name to the more generic National Foundation.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Bad moves. The lack of something specific to fight contributed to what by the late 1960s would be a 75 percent decline in real fundraising from that 1954 peak. So O’Connor shifted tactics again in 1965, declaring the National Foundation would dedicate itself simply to fighting birth defects. Contributions eventually began rising, so much so that in 1979 the National Foundation changed its official name yet again, adding “birth defects” and, for the first time, “March of Dimes” so it became March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation.

In 2006, reports Barrett, it opted to end its focus on birth defects altogether, but even with all of this effort, the organization never regained the same prominence in the hearts of donors. On that 2016 990, the year’s revenue is listed as $169 million.

There’s no question that the building sale may alleviate cash flow problems in the short run, and maybe even a little in the long run by eliminating fixed costs related to the building, but in a situation in which deficits are so consistently tolerated, the problem may lie elsewhere.

Part of the statement given by Todd Dezen, a spokesman for March of Dimes, sounds eerily familiar, as an attempt to frame and minimize: “As the March of Dimes approaches our 80th anniversary, we’re taking action to transform into a modern and sustainable organization that will be around for at least the next 80 years to support pregnant women, families, and babies across the country.”

As we know, however, this is the kind of story that will intrigue investigative reporters who might be interested in whether the organization has really come to terms with its apparently longstanding need for a meaningful financial reboot. If we needed another example of how size is no prophylactic against elemental financial mistakes, this may be it. —Ruth McCambridge