Truth to Power is a regular series of conversations with writers about the promises and pitfalls of movements for social justice. From the roots of racial capitalism to the psychic toll of poverty, from resource wars to popular uprisings, the interviews in this column focus on how to write about the myriad causes of oppression and the organized desire for a better world.

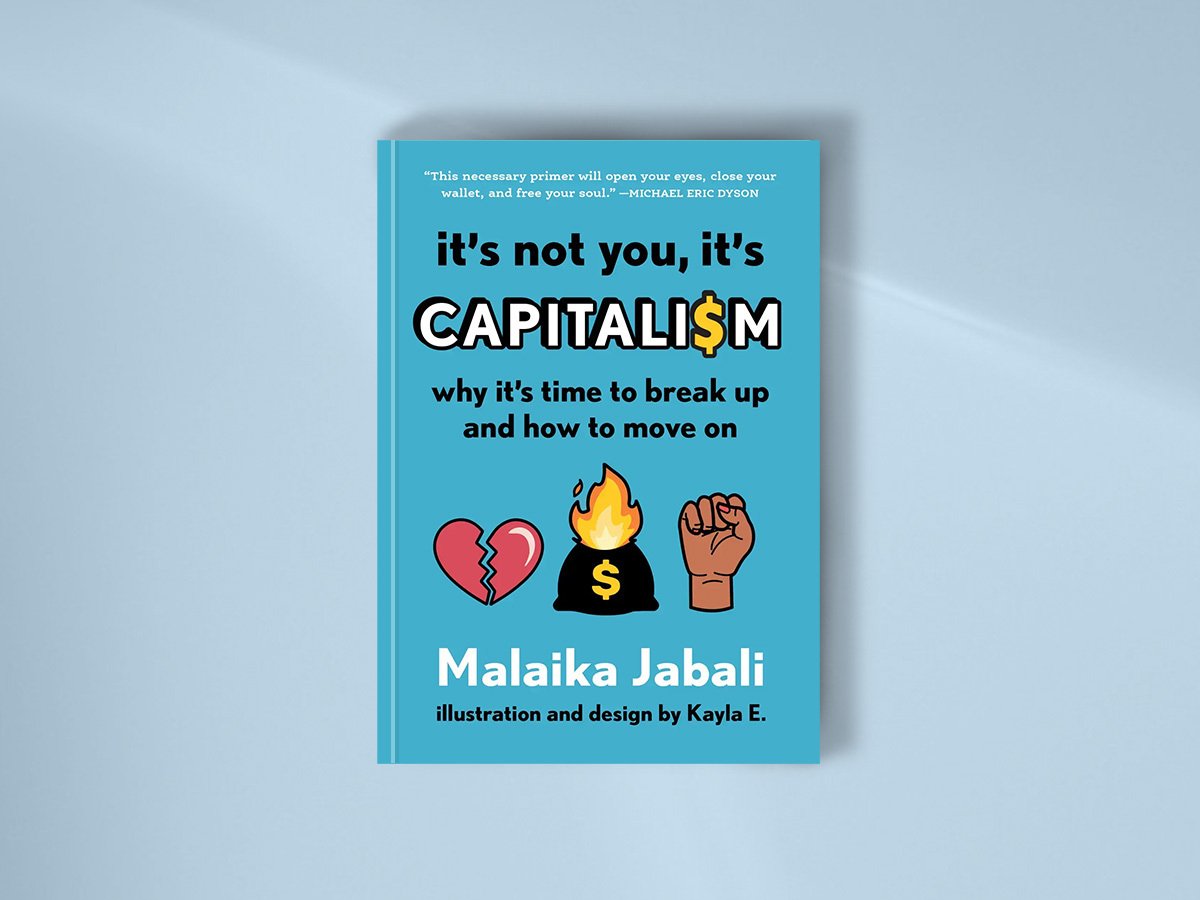

Rithika Ramamurthy: The key argument in your book is about capitalism being a toxic partner that we all need to break up with, that’s jealous or draining our energy or negging or gaslighting us. Why did you use this metaphor?

Malaika Jabali: When I was doing a first pass at the draft and writing the earlier chapters, I wrote that we should just “dump this mfer already,” because I was seeing these patterns of us getting all these promises from capitalists and them not delivering. When are we going to start looking at other options?

Relationship metaphors came up organically as I was writing, but it really crystallized when I read people’s stories on Twitter. There was a person who was complaining about the fact that he had to work two jobs, how exhausted he was, and that his wages just weren’t adding up to pay his rent. In the comments, people dismissed him saying that he just wasn’t stepping up enough, suggesting that he should get a third or fourth job. I literally said out loud: “it is not you, it’s capitalism. It’s not your fault.” So that led to a full-blown guide to breaking up with the current system.

RR: I want to talk about the book’s style. It’s funny and conversational but serious about its subject, full of both socialist theory and memes. What did you do to balance comedy with argument?

MJ: I think discussions about capitalism and socialism can be very academic. I am hoping that using metaphors that relate to people’s everyday life will make this book more approachable for the people who might already lean towards thinking about alternatives, but also to people who might not have ever thought about it.

Part of the difficulty was being able to dissect and translate the appropriate authorities in a way that people understand and appreciate. For example, I quote Marx and Engels quite a bit, and had been reading Marx’s book Das Kapital. The book itself is very difficult, there are formulas in it—and I’m not a math person. Instead of using a term like “surplus value”—a Marxist term defining the value labor creates for capitalists—I called it profit. I wanted people to grasp what it means when everyone is working a lot and a small amount of people are able to exploit our labor and use the money to their benefit.

Our movements are supposed to be led by and largely consist of the working class. Using language that is too abstract to grapple with might not energize the everyday person. How are you going to motivate people who are feeling the brunt of capitalist exploitation today who have no economic security? I can write a research paper, but will it move people? I want to move people into action.

I feel like humor can bring people into a fold. If people are willing to just pick up a book, they can engage with the theory. I interlace the book with a lot of theory, with philosophers, with the philosophy of Black scholars and activists. If you read their original text, it can be hard to get through, but it is important information and context. It was almost like writing a sitcom: introduce with a joke, put it in the meaty stuff, have a button every other paragraph. It helps people digest a serious conversation.

RR: You state clearly that envisioning another system isn’t the problem, it’s political will to organize for something better. “Not to get all bootstrappy in a book on socialism, but we really do have some responsibility in getting the kind of relationship we want.” Can you talk about what you mean?

MJ: At this point, many people across the political spectrum recognize that we need alternatives. Many people are suffering, and both the people in power and the people struggling know that wealth inequality in the US is untenable.

“There is better out there—but we have to work for it.”

The question is: how do we take that knowledge and translate that into a political project? We have such extreme polarization in American government; as much as you might agree with somebody, you might not vote for them because they’re not on your “team.”

To get around that tribalism ingrained in American politics, we need to put actions behind our thoughts. One of the examples in the chapter on healthcare is from the 2020 South Carolina Democratic primary. A majority of voters supported replacing private health insurance with a universal government plan. The poll didn’t use the term “Medicare for All,” but it’s obvious that’s what it meant. But the South Carolina primary showed that people didn’t go for the candidate that proposed that policy. There is so much messiness in the ways that we express our political ideology that doesn’t reflect our policy interests.

RR: There’s also the flip side of this, which is that most people are so crushed by the system that they feel nothing will change. What do we say to them?

MJ: There is better out there—but we have to work for it. I think it’s easy to be deflated by this moment, but I look at history overall. A few generations ago, a Black woman like me would not have been considered human. My great-great-great grandparents were less than citizens—they were considered machinery. Black people were enslaved in this country longer than we’ve been free. But here I am writing a book and being interviewed about why we deserve better.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

That change didn’t come by happenstance. It happened through people’s resistance, through their hope and faith. You could call it delusional optimism, because nothing in their environment told my ancestors that there was a way out. If I was alive in that time, I might not have thought there was an alternative—why would I? If we could get through that and change things, we can do anything.

RR: One of the planks for power building that we need to flip this script is of course, building political power. That can happen in the workplace or community organizations, but one thing we can’t avoid is electoral organizing, which many people have fallen out of love with for obvious reasons. Where can we look to find hope in that, in your view?

MJ: We should look locally. It’s much harder to see wins at the federal level, where billions of dollars are spent to win elections. On a strategic level, we see change happening in city councils, state and county governments, with everyday people deciding to run for office fighting for our interests.

“That change didn’t come by happenstance. It happened through people’s resistance.”

I’m a socialist, so I know there are many ways that we can be deflated. Across the board—from the White House, to Congress, to the Supreme Court—we lose a lot. Not only do we get our policies shut down, but people don’t even want to hear the rhetoric. People think if you’re critiquing the system, you’re allowing us to descend into fascism. Ideologically, it’s hard to be a socialist, so concrete wins are valuable for the movement not only for optimism, but also obviously for policy reasons.

There’s a treasury at the local and state level. When you look at the way state and municipal budgets are run, they are handled by legislatures, as in the state Senate or city council. They can control what we do with it. Can we invest in a community land trust? Can we create laws to give people money? In New York City, there was discretionary funding for nonprofits in the budget. Are there nonprofits working on this? We can use these legislatures to our advantage.

I worked on the Land Use committee when I was working for the New York City Council. I learned that developers are going to make plans regardless of what socialists decide to do. They are making plans that are displacing people. They are making plans that are raising rents. They are making plans that are keeping homeless communities from having housing. They are making plans. What are we doing? We can be the ones making those decisions, and people need to get involved in the process and understand it’s going to happen without us anyway.

I understand people’s reservations with the federal government. To be real, a lot of times they don’t get things done. We had the largest mass movement for social justice in history during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, but we have yet to pass a federal bill for police reform. There are Congress members who say that they’re progressive, but they’re still passing large defense budgets that could be going to domestic issues. But electoral politics is not just what’s happening in D.C.

RR: As a politics editor for a popular platform of Black culture, what do you feel the needs or good examples are in media for accessible anticapitalist writing, especially stuff that centers race?

MJ: I wrote this book because I saw a void in the field, and I was asked to create something accessible that centered people of color and women of all races. There are scholars I admire—Keaanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Robin D.G. Kelley, and others—making those race and class connections. But part of the reason I wanted to work at a Black media outlet is that a lot of us are online, and I need to be in a space where everyday Black women are.

Part of the underlying motivation of my book is how to reach people like my friends, Black women who are disproportionately harmed by capitalism but don’t see many critiques that are made for us. I quote a lot of Black women in this book, and talk about Black-led movements and movements led by women of different races, to show that socialism is something rooted in a Black radical tradition. It’s a tradition that I came out of, and I want to share it with other people.

RR: Anything else you want to add?

MJ: I wrote this book to make people a little bit angry. The point of writing about the problems of capitalism and socialist solutions is to motivate people to do something with the information. When you break up with someone, a little bit of anger helps you in your “revenge era.” I think fire helps people who want to take the next step.

In my mind, we’re at a crossroads right now, where various leftist movements have been deflated and the promise of electoral politics pushing socialism forward has not transpired.

There are people who may have been willing to think about class issues, but they have been influenced by white supremacy and patriarchy. Instead of focusing on the larger system at play where all of us are suffering, we’ve been letting these get in the way. Hopefully, this book can help pull people who are empathetic to these views off the ledge and push them to organize others.

As a journalist, I talk to a lot of people about what they are going through. My strategy with this book was not talk about party politics too much and try to connect to people’s instincts instead. People out there are concerned about what is messed up in the world, they have a hierarchy of needs. Rather than talk about larger, abstract topics like democracy or even climate change, I wanted to break down our issues into what is most tangible. Socialism gets at the root of life: people want to be healthy, they want homes, they want education. That’s where the book came from—from thinking about what people need.