This article was published in the Fall-Winter 2013 double-sized issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “Networks and Leadership: Emergence and Transitions.”

A local arts organization had been a vital part of the community for decades, providing inexpensive space and support for artists, opportunities for children and others to explore art, and a stage for local theater. A new chief executive was to be recruited, and the organization aspired to find someone who would revitalize the organization and its capacity to attract relevant and inspiring art. The major contribution this organization had to offer was space for artists and the community that grew in that space. However, the artists who had been present at the founding of the organization, twenty-five years prior, occupied over 90 percent of it. While a few were very active, the majority of them were semiretired or used their spaces sparingly, but were unwilling to give them up. The unspoken “plan” was for space to be occupied by new artists only as people died or retired fully. The rhetoric of the search was for a new vitality, but the reality was something else. The dynamic executive director who was recruited did not understand this, and she quickly was undone when she proposed a criterion that all resident artists must be accepted into at least three juried shows each year.

When embarking on the search, the board implicitly understood that the precious studio space was going to be defended by the founding artists. They imagined that this new executive director would somehow find a way around this. The opportunity missed by the board was that it could have used the search, and particularly the conversation with top candidates, to explore the difficult question of how to revitalize the organization when the space was so jealously guarded. Assuming that the top candidates were the experts, the board had a chance to grapple with how the issue might be solved. Its members missed an important opportunity to come to terms with a new chief executive making the best case for how she and the board might overcome the barrier together.

There is yet a larger and more dramatic point here. The demon or “third rail” of this issue was powerful in part because it was only acknowledged offline and in whispers, although anybody familiar with the organization understood the circumstances.

How do these awkward realities get communicated to a candidate for an executive position?

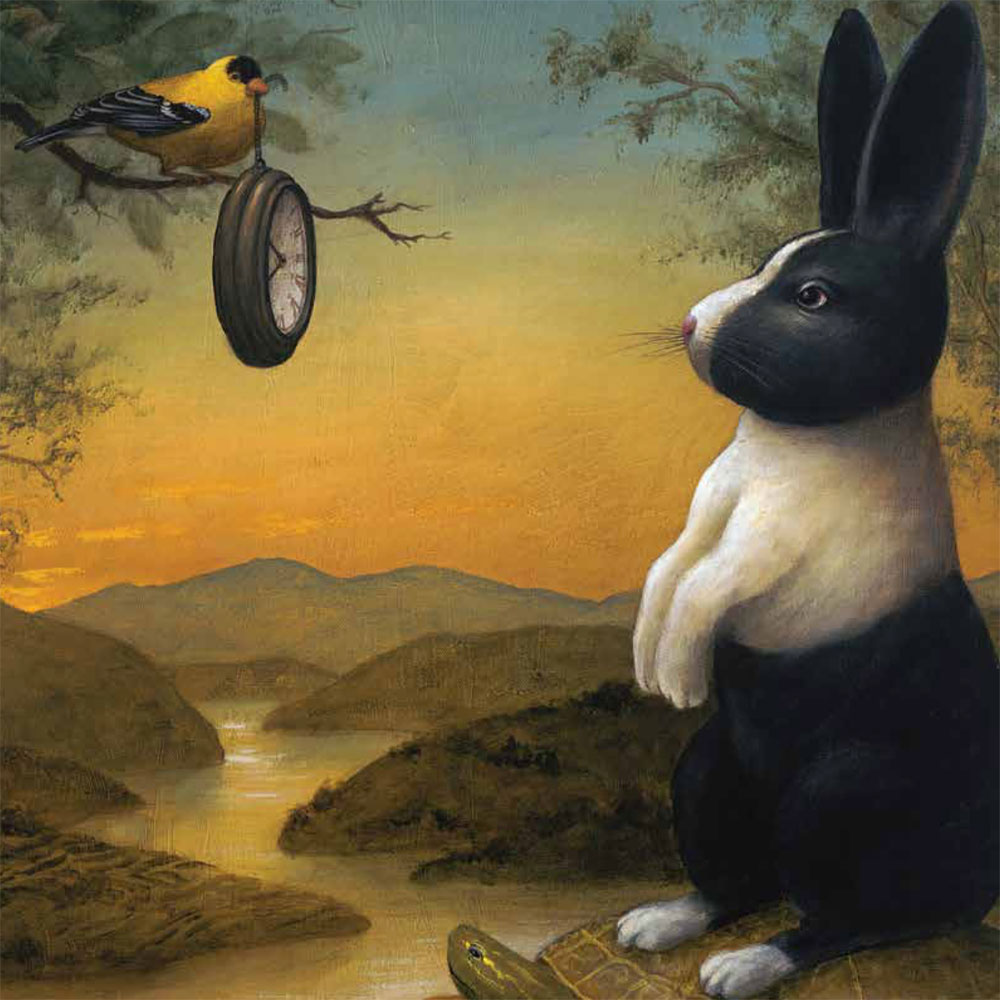

Remember the scene in The Wizard of Oz where the all-knowing Oz is revealed to be an uncertain man behind the curtain? So often the instinct of organizations when embarking on a chief executive search is to remain behind that curtain and declare that all is as it should be—when it isn’t. Absent a Toto tugging on the curtain, the conversation with chief executive candidates often fails to address the most challenging and important issues in play. Is it any surprise that misunderstanding and conflict and bad executive choices result?

It is in the nature of every organization to struggle with contradictions. Anyone who is equipped to be a chief executive knows that there are myriad complications that are part and parcel of the role: board politics, destructive competition and conflict among silos or ambitious staff members, funding requirements that skew the original mission and strategies of the organization, and staff managing complex programs without proper training or supervision. These and other contradictions are often present and await the new chief executive.

The ideal forum in which to determine how difficult organizational issues will be solved and a promising vision fulfilled is in that space between the chief executive and the board. It is for the board, which governs the organization, to establish that space as one in which the critical issues will be faced head on—where all the sacred cows are brought to account and unacknowledged elephants (the unmentionables) named—because they will, at least in large part, define what is truly possible in the situation. There is no better time to address this than when searching for a new chief executive. A hiring process provides a discreet forum in which to address difficult, defining issues. It is, ideally, a forum in which the board can raise such questions in a constructive manner, challenging candidates to provide advice and insight. These open conversations often liberate the board from the burden of unspoken but critical issues. With this action, the board is establishing a critical standard: the challenges most material to the success of the organization are going to be front and center in the relationship between the board and the chief executive.

One would like to think that this is always the case, but most readers of this article will understand that, unfortunately, it is not. The board, which is the supervisor of the chief executive, often signals, intentionally or by default, that there are certain issues that the chief executive should not confront—even, as in the example of the local arts organization, when those issues are central to the rhetoric of the organization. The result is that the board, as it shapes its relationship with the new chief executive, begins that relationship by being less than fully honest. This starts the cycle. Is it any wonder when board members later complain that their chief executive is not being fully open with them?

Dorothy could not get back to Kansas until she and the man behind the curtain together acknowledged the reality of their circumstances. After that revelation, they were able to solve the problem. Dorothy had spent most of her journey seeking the wrong source, and the man behind the curtain had spent his energy pretending to have the answer. Both would have gotten there sooner, and avoided that unfortunate incident with the flying monkeys, had Oz signaled that he was ready to deal with reality from the start.

Back in Kansas

Hindsight is easy, and the examples in this article (above and in the sidebar, at bottom) become clearer with the passage of time. In real time, it can be very hard to recognize or give voice to an essential truth, especially when the organization has habits that block open communication—habits like excessive politeness or only third-party communication of concern. This is why for many organizations it may be worth the price to invite someone in to help map the landscape before the hiring process starts. There are relationships and friendships to weigh, and past challenges and successes that need to be remembered and respected. There is the push and pull of different and mostly well-meaning agendas. And even the right choice is not without its uncertainties. This is why I try not to be prescriptive. There is no one way forward. It always depends.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But there are at least two larger truths that always apply that can help a board navigate the endless complications of governance:

Rule 1. There is no substitute for honest dialogue.

Rule 2. No one is above the organization.

A founder, a powerful chief executive, a unified board, a dominant group of long-term board members, a major funder—or combinations of the above—often shape and control an organization. And usually they do so to good purpose: they overcome adversity; they find the resources to keep things going; they lead and inspire by example and hard work. If they are the founders, they had the vision, took the risks, and often worked without pay or security. For all these reasons they should be honored and celebrated—but they are not above the organization. This point is important because this positive and creative intensity can have a downside, as it can also narrow the organization’s field of vision. And, the power dynamics are such that it is difficult for those who are outside this circle to promote another perspective and be heard.

My experience is that those who are in this circle of leadership are usually aware of countervailing needs and issues, at least in the back of their minds. But they may need help to introduce those issues into the dialogue with top executive candidates, for it is in the exploring of these difficult or even conflictual spaces that the right next executive may distinguish him- or herself.

In the end, an executive transition is a rare opportunity to take an honest look at the organization. This allows the next leader to be presented with the truth and with that space between the board and the executive properly defined, so that his or her life is not filled with the scourge of flying monkeys.

More Flying Monkeys…The Founder’s Board A charismatic founder had built a national organization with the support of a generation of luminaries from the government, business, and entertainment spheres. Well past retirement age but still vigorous, the founder continued to support the organization by drawing from his fading network. Access and funding for the organization was almost entirely dependent on his connections and his promotion of the programs. While the mission was still vital and important, the staff and infrastructure necessary to facilitate succession was not in place. The board was a founder’s board—composed of longtime friends and supporters. To a person, the board members were concerned that the organization might not survive the founder’s departure, absent a radical redesign of the entire enterprise. But they could not confront him. They put the founder above the organization. Living in the Past An international development organization, with a board largely composed of those who had previously worked for the organization, had enjoyed the service of a dedicated chief executive for nearly twenty years. The organization had tremendous good will, both within its membership and in the countries where it did its work. The chief executive was deeply committed and hardworking, but his focus was entirely operational. He didn’t fundraise, nor did the board. The strategy, such as it was, depended on generation after generation of volunteers to carry the organization. With bake-sale type activities and a modest tuition, and staffed by low-paid, young, energetic former volunteers, the organization lived hand to mouth. With the chief executive’s retirement, the realization was that the organization did not have the professional staff, infrastructure, board discipline, development, and financial resources to sustain itself over the long term. In the face of ever more strict regulations, growing risk-management challenges, and competition, it had to grow and improve productivity to achieve the economies of scale that would assure its financial stability. The power of this example is that the organization was wonderfully successful by almost any measure. There was a strong and genuine sense of community among the board and staff. Good work was being done—but it was not sustainable. |