This article is the first in a series of articles about co-op leadership and power. The next article will highlight the work of Black co-op leaders.

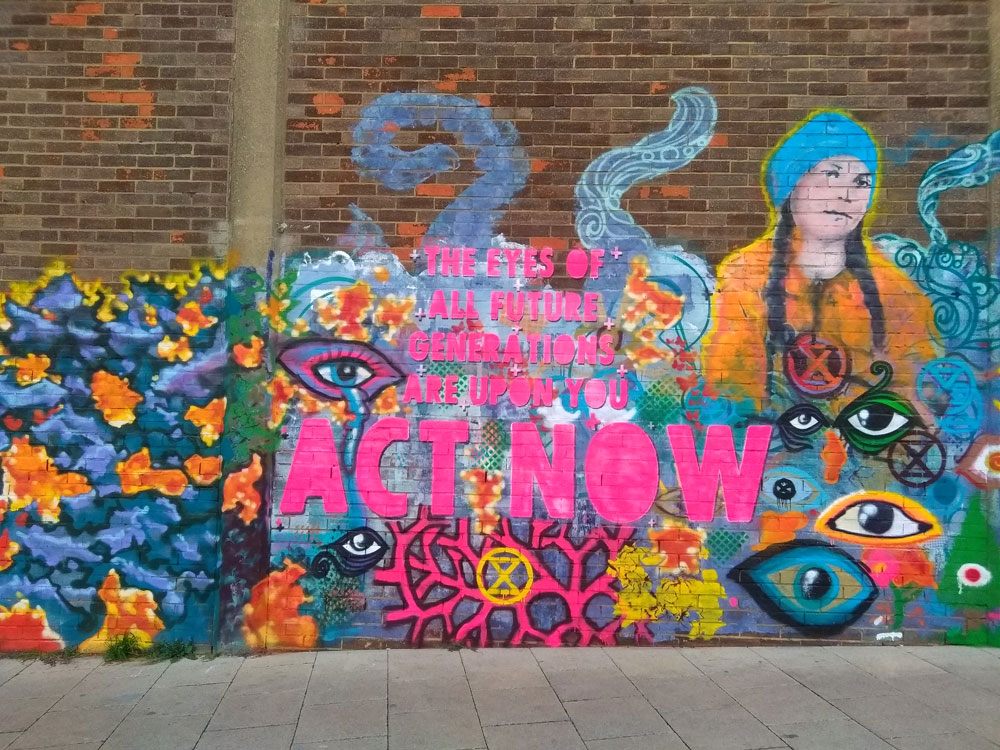

Now is the time for food co-ops, food co-op consultants, and funders to move from thoughts and prayers about social and economic inequities to dealing with issues of power. The food co-op community is tasked to do more than build and sustain grocery stores—we need to address social justice and wealth inequality.

In a time of COVID-19, extreme inequity, and ecological disaster, democratically owned and controlled grocery stores that are truly representative of their communities offer solutions to these multiple challenges.

When the red-hot glow of this pandemic burns out and the reports of recovery start to hit the news cycle, the struggle will continue to be one of life and death for vulnerable communities. The essential workers—those who have picked our foods, rung up our groceries, processed meats, and sanitized food facilities—will still be struggling with substandard housing, lack of access to good education, chronic underemployment, and, ironically, lack of access to affordable and nutritious food. The virus will eventually be suppressed, but the conditions that allowed the virus to spread with such devastating effects will remain the same. Unless we design for something different.

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard’s book, Collective Courage, details the history of cooperative economics in African American communities since the time of slavery, throughout the civil rights era, and beyond. These communities have applied cooperative principles and economics to provide much-needed goods and services, with a focus on development and sustainability. Collective Courage is not just a retelling of the past but a description of what is needed, now and in the future.

The present catastrophe is, in theory, what cooperatives are built to avoid, and to fix. Co-ops are designed to meet unmet needs in our communities and respond to system failures. Before this pandemic, many food co-ops, feeling the pressure of increased competition and thin margins—like the grocery sector at large—were going back to their roots, with a renewed focus on the unique value proposition of the cooperative model.

Cooperatives have seven internationally recognized principles:

- Voluntary and open membership

- Democratic member control

- Member economic participation

- Autonomy and independence

- Education, training, and information

- Cooperation among cooperatives

- Concern for community

There is comprehensive guidance provided by the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) for each of the seven principles. The seventh principle—“concern for community”—means that co-ops pledge to work for sustainable social development of their communities through policies approved by their members, including social justice.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The ICA guideline (page 90) for the principle reads:

This 7th Principle of working for “the sustainable development of their communities” also requires that co-operatives accept responsibility for making a contribution to tackling poverty and wealth inequality, not only between developed and emerging economies, but also the growing wealth inequality in nation states and in the local communities within which cooperatives operate. Co-operatives are excellent at tackling poverty reduction and combating wealth inequality because their nature is to create wealth for the many, not the few.

The Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future (page 41) explains the concept of sustainable development in greater detail:

The satisfaction of human needs and aspirations is the major objective of development. The essential needs of vast numbers of people in developing countries for food, clothing, shelter, jobs—are not being met, and beyond their basic needs these people have legitimate aspirations for an improved quality of life. A world in which poverty and inequity are endemic will always be prone to ecological and other crises.

In spite of the clear guidance in the co-op principles, food co-op leadership in the US— the gateways of knowledge, the sense makers of data, the interpreters of principles, and the distributors of funds—is largely white-led.

Food co-ops are not immune to the dominant culture, but we do have a responsibility to live up to our principles.

A new wave of leaders is currently organizing in Black, Latinx, indigenous, rural, immigrant, and communities lacking in monetary wealth. Startup food co-ops are developing equitable local food systems, creating good jobs, and rebuilding local economies. These leaders know that a food co-op isn’t a luxury item but the lifeblood of their communities.

For the co-op movement to truly live out its principles and become a more powerful tool for wealth equality, Black co-op leaders need more space and power.