January 28, 2015;Reuters

In this time of renewed attention to the disastrous effects of systemic racism, the NPQ Newswire is revisiting history important to the Civil Rights movement because it lays a historical base for the actions being taken now. Civil disobedience, as readers know, has been a mainstay of the “Black Lives Matter” movement, so there should be great interest in the “jail, no bail” tactics of these men. A video that explains that idea more completely is included here.

Yesterday, in a Rock Hill, South Carolina courtroom, the “Friendship Nine” who staged a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter on January 31, 1961, were absolved of their convictions for trespassing. The action to vacate the convictions was based upon the idea that new evidence could cast doubt on the validity of a conviction.

“What we have in this case is not something you can hold in your hand,” local prosecutor Kevin Brackett said, however. “It’s more of an evolving consciousness and evolving awareness of the wrongfulness of the policies of that time.”

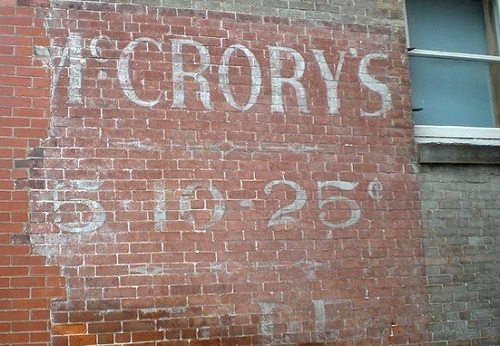

At the time, most of those who dared sit at the lunch counter of McCrory’s five-and-dime store were students at the now-defunct Friendship College. The “Friendship Nine” were reportedly the first group of civil rights demonstrators to choose “jail, no bail” over a fine for sitting at a segregated lunch counter. Many others later used the strategy.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history,” said Judge John C. Hayes III, who vacated the sentences. (Hayes is, in fact, a nephew of the judge on the original trial.) He also vacating the convictions of several other protesters who were arrested in Rock Hill as they protested in solidarity with the original nine.

There are eight surviving members, but only seven attended the hearing, represented once again by Ernest Finney Jr., a civil rights lawyer who represented the group originally and eventually went on to become the first black chief justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. The men were convicted on February 1st, 1961, and served 30-day sentences at the county prison farm. Their names are David Williamson, James Wells, Willie McCleod, Willie Thomas “Dub” Massey, Clarence Graham, John Gaines, Thomas Gaither, Mack Workman, and Robert McCullough. Some of the men said that they felt the burden of a criminal conviction on their lives for years.

Local prosecutor Kevin Brackett, as he apologized to the men, noted that they did not want their arrests expunged from public documents because it was important for the documentation of history to leave them there. “There is only one reason these men were arrested…and that is because they were black,” Brackett said. “It was wrong then; it’s wrong today.” He also revealed that he had been approached with the idea of “pardoning the men,” but he said that a pardon would have implied forgiveness, and that the nine had done nothing wrong to forgive.

Judge Hayes agreed that the arrest records should stay on the books, “This will remain part of our history as corrected,” he said.

Clarence Graham, now 72, said the sit-in “wasn’t for any glory…. We were simply…students who were tired of the status quo, tired of being treated as second-class citizens.” Graham said he hopes that younger people will take note. “Even though we were treated unjustly, still nonviolence prevailed,” Graham said. “You think we’re going to sit down and rest now? No, no, no. We’ve got to lead by example.”—Ruth McCambridge