This article is part of Black Food Sovereignty: Stories from the Field, a series co-produced by Frontline Solutions and NPQ. This series features stories from a group of Black food sovereignty leaders who are working to transform the food system at the local level. It explores how these leaders are addressing critical issues at the intersection of food sovereignty, racial and economic justice, and community.

How can a community reduce food insecurity? For over 30 years, the Camden Dream Center, which I direct, has addressed food insecurity through a food pantry, which works in in partnership with the Food Bank of South Jersey to serve well over 1,000 families per year in Camden and its vicinity.

Food pantry work is important. But the Center aspires to do more—to advance economic empowerment in an environmentally sustainable way. One strategy for achieving that vision is to support urban agriculture and community agency, giving people the chance to produce their own food.

Advancing urban agriculture in Camden

How do you move from dependency on charitable food to cultivating your own food? It’s not easy, the process requires a drastic shift in mindset among those involved. In particular, increasing Black youth involvement in farming requires that we first erase the connotation that farming has for many Black youth of slavery and sharecropping.

And we must do so while addressing both the historical legacy and contemporary reality of racism. It is not enough to fund the problem. Dismantling barriers to food access requires clear strategies and methodologies that inform funding, drive policy, and guide community-based initiatives. While the answers remain complicated, we must use our collective power and community agency to address our needs.

A Camden community vision emerges

Census figures confirm that Camden is a poor city (with a poverty rate of 33.6 percent) and overwhelming BIPOC (50.5 percent Latinx, 42.5 percent Black). What the numbers do not show, however, is that Camden is a city full of problem solvers and residents who are eager to improve their city as well as their living conditions.

Camden is also home to young people who regularly show incredible power and strength. However, persistent poverty plagues the city’s residents. Low wages and/or benefits are insufficient to meet high costs of living; the average Camden resident spends nearly half of their $27,000 median household income on housing. Divided by multiple highways, Camden, a hyper-local city whose many residents largely stay within its border, lost its only major supermarket in 2021, and lack of transportation impedes residents from accessing healthy food, as well as social support resources. Residents purchase food at local small businesses, where prices are higher than at larger grocery stores and healthy food options fewer. Though robust, the city’s network of supplemental food distributors can be complex and time-consuming for residents to navigate, limiting access to healthy foods.

As in other cities, in Camden, dedicated community-based organizations are working to close these gaps through nutrition education, food assistance programs, and social services. For example, the Food Justice Innovation Hub, which the Center is developing in partnership with community groups, aims to develop the local food system infrastructure necessary for sustained food security.

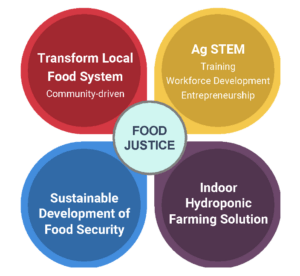

The centerpiece of the Center’s strategy, backed by a grant from Feeding America, involves developing a vertical hydroponic farming facility, which will help feed residents while increasing intergenerational knowledge of sustainable farming practices. The hydroponic controlled environment agriculture (CEA) project is based on an IoT (Internet of Things) platform with sensors that allow for careful monitoring of growing conditions. The facility is designed to increase participation of underrepresented students in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math), Computer Science (CS), and Agricultural Science (AS). Participating students learn about controlled environment agricultural management and the underlying technologies—eg, sensors, data collection, and data analytics—and the operations and maintenance of an indoor hydroponic farm. The figure below describes the innovative hub and its components.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Putting the Food Hub Together

To achieve the food justice vision depicted in the diagram, all stakeholders must work together to develop strategic alliances and comprehensive strategies that support common goals, drive real change, and create equity. Harnessing the power of marginalized communities requires a comprehensive approach that addresses our communities’ complex needs. This involves work in the following four areas:

- Transforming local food systems demands moving from a dependent charitable food pantry model to a sustainable local food system. This includes: a) developing a distribution process for farm yield; b) establishing neighborhood co-location of multiple services for food delivery; c) leveraging the value of federal SNAP (Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, also known as food stamps) and WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants & Children) benefits; and d) expanding agribusiness opportunities for residents and local businesses.

- Agriculture Science and STEM Education requires working closely with school districts, colleges, and universities to expand educational opportunities and career pathways to support a sustainable local food system. Training scholars using recognized national certifications and curricula focused on hydroponic systems technology, urban agriculture, natural sciences, and farming management will create a workforce for in-demand agricultural occupations that pay livable wages.

- A vertical farming (VF) solution for urban areas is not only sustainable and scalable; it can outproduce a traditional farm of like size in a similar climate. One 40-foot vertical farm can grow 365 days/year and produce annual yields equivalent to those produced on up to four acres. VF enables large-scale agricultural production in environments where space and soil are limited. Hydroponic VF solutions use no soil and as much as 90 percent less water than traditional farming. A hydroponic VF solution will grow fresh produce year-round without pesticides or herbicides, improving the quality of food available to families, seniors, and others seeking to control what they eat.

- Sustainable development for food security warrants local and national metrics that demonstrate reductions in disparities for marginalized communities, such as those utilized by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s), which strive to end poverty and hunger by 2030. The report, Never More Urgent, reveals that the greatest disparities facing Black and Brown people in the United States are in five main areas: justice, food and housing security, education, economic security, and health. A related report, In the Red: The US Failure to Deliver on a Promise of Racial Equality, indicates that white communities are receiving sustainable development education, resources, and opportunities at three times the rate of communities of color, leaving us behind. The Food Justice Hub is designed to ensure that culturally relevant approaches engage our communities in sustainable development.

Beyond the four areas outlined above, addressing social determinants of health—which include poverty, hunger, quality education, health, and wellbeing—is key to the Camden Food Hub initiative. To do so, the Center’s partners at the Food Bank of South Jersey and the Camden Coalition have engaged a broad set of stakeholders, including community residents, health systems, industry, schools, and public agencies.

These meetings are needed to develop the wrap-around and comprehensive services necessary to help people navigate disjointed systems. Such services include economic development, critical thinking skills and decision making, veterans and reentry services, mentoring, leadership development, early childhood development, and addiction recovery.

This work also requires partnerships with federal, state, and local agencies, including the US Department of Labor (DOL), state departments of labor, education, and agriculture, chambers of commerce, and others. Longstanding relationships with school districts, colleges, and universities are also critical to advance equity at the neighborhood level.

Cultivating agency

Those of us who lead predominately Black and Brown organizations know injustice and inequity. However, we often lack resources and tools to effectively measure our impact in dismantling those injustices.

To better address racial disparity and develop our food justice model, the Center has researched not only racial equity models, but current “DEI” (diversity, equity, and inclusion) approaches. Unfortunately, such approaches rarely speak to specific neighborhood needs. Instead, most DEI efforts are led by human resource professionals with limited understanding of communities like Camden.

Earlier this year, famed community development scholar John McKnight recalled that when he started studying urban issues in the late 1960s, many urban studies scholars were “looking at neighborhoods and especially lower income neighborhoods in terms of their problems, deficits, needs, and brokenness…their deficit approach did not see that the people who lived in the neighborhood had some agency, some ability, some capacity, because all of their work was to help institutions come in and fix us. And I just thought that was insulting.” It would be nice to say that such an analysis is no longer applicable, but we know better than that.

This raises an important point—namely, this is not just a story about Camden. We are part of a broader national movement for food justice, urban agriculture, and sustainable development. And we are seeking to develop a new paradigm of economic development—one that centers community agency, production, and self-sufficiency, rather than promoting a model that centers dependency and begging philanthropy for crumbs.

In short, communities must be able to tell their own stories. We must set goals and strategies that increase equity, reduce structural barriers, and strengthen belonging and identity. We must self-organize to move the needle, meet critical community needs, and exercise our collective power.

Like many organizations, our Center sees this work as a calling. We believe it is our life’s purpose and passion to serve others as equal partners and co-producers of change. This requires approaching our work with cultural humility and servant leadership, as we move from dependency to agency.