According to research first published in JAMA Network Open, members of Generation X (which includes people born between 1965 and 1980) have a greater chance of being diagnosed with cancer than any generation before them.

The research paper, “Cancer Incidence Trends in Successive Social Generations in the US,” authored by Philip S. Rosenberg, PhD, and Adalberto Miranda-Filho, PhD of the National Cancer Institute, asks the fundamental question: “Are we collectively experiencing lower cancer incidence as we age than the generation of our parents?”

The study uses data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program’s registry databases to examine the rate at which people are newly diagnosed with cancer. The 13 databases, which the researchers accessed on August 14, 2023, included 3.8 million individuals diagnosed with invasive cancer (51 percent of these individuals were men and the remaining 49 percent were women).

The patterns detailed in the study are based on the estimated cancer incidence per 100,000 people at the age of 60. In other words, the study asserts that when Gen Xers start turning 60 in 2025, they’re more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than previous generations were at the age of 60.

“Are we collectively experiencing lower cancer incidence as we age than the generation of our parents?”

Compared with baby boomers (people born between 1946 and 1964), Gen X women were more likely to be diagnosed with thyroid, kidney, rectal, uterine, colon, and pancreatic cancers, as well as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and leukemia. Gen X men are expected to have higher rates of thyroid, kidney, rectal, colon, and prostate cancers, as well as leukemia.

Though the overall trends regarding cancer diagnoses projected higher rates of cancer for Gen X than baby boomers and other previous generations, there were a few kinds of cancer that are projected to occur less in Gen X. For Gen X women, the projected decreases include lung and cervical cancer. For Gen X men, the data projects lower incidences of lung, liver, and gallbladder cancers and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The data led the study’s researchers to conclude that “Generation X may be experiencing larger per-capita increases in the incidence of leading cancers than any prior generation….On current trajectories, cancer incidence could remain high for decades.”

Generational Cancer Risk According to Race/Ethnicity

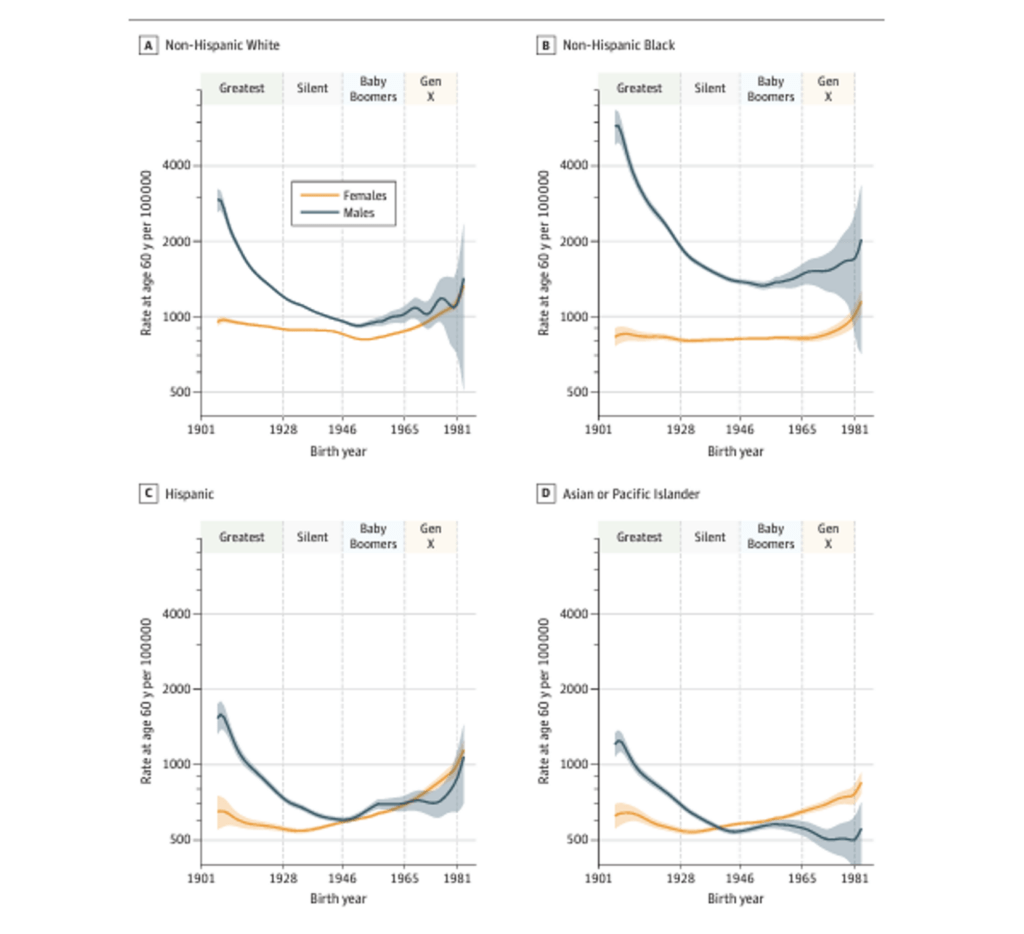

The increased rates of cancer among Gen X also reflect general disparities in cancer diagnoses by race and ethnicity. The study examined cancer incidence for non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, and Asian or Pacific Islanders.

For each of the racial/ethnic groups included in the study, there was a downward trend for the generations born between 1908 and 1945, known as the greatest generation and the silent generation. Then, the trend line begins to level out or rise for baby boomers and Gen X.

Though rates of cancer diagnosis among men and women—from both an intergenerational and a racial perspective—are complex, some important trends are worth noting.

For men in all four of the racial/ethnic groups included in the study, cancer incidence rates at 60 years of age declined for the greatest generation and silent generation. Among women, cancer incidence was fairly stable for members of those generations “and then increased beginning with the Baby Boomers for non-Hispanic White individuals, then the Silent Generation for Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander and Generation X for non-Hispanic Black individuals.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

By Generation X, Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women were trending toward parity with their male counterparts, though Asian/Pacific Islander women had a higher incidence rate compared to men. Among the Black population, men’s cancer diagnosis rates exceed rates for women across generations.

Reasons for the Shift

“Generation X may be experiencing larger per-capita increases in the incidence of leading cancers than any prior generation.”

Ironically, the higher cancer diagnosis rate is, in some ways, a good thing. Corinne Joshu, a cancer epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told ScienceNews that it’s “hard to say how much of this is related to changes in detection and changes in…clinical awareness.” For Joshu, this makes it difficult to ascertain whether the increase in cancer diagnoses reflects “a true increase” in cancer rates overall or an increase in cancer detection. The latter could offer some positive news, as early cancer diagnosis improves health outcomes, quality of life, and a person’s likelihood of remission.

The rising cancer diagnosis rates for Gen X have been attributed to “lifestyle factors” such as obesity, low rates of exercise, and a diet that contains too much red meat. Though diet and exercise are important, they should be balanced against the understanding that all populations do not have equal access to fresh, healthy foods, environments conducive to physical exercise, or adequate medical care. Rather than evoking the neoliberal imperative of “personal responsibility” and “self-management” as the sole or even primary contributor to rising cancer rates, the availability of resources and environmental factors should be of paramount concern.

One of the environmental factors that could be linked to increased incidence of cancer is the prevalence of carcinogenic exposures. Carcinogens are chemical substances that can increase one’s risk of cancer. And they are increasingly prevalent in some foods (like red and processed meats), food packaging, and asbestos. Chemical plants and other environmental hazards like wastewater treatment plants, which are most often placed in Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and other economically or socially disenfranchised communities, also release carcinogens into the water and air.

Since the cancer rates for Gen X are based on projections, we still have time to change their outlook—and that of the generations to come—for the better.

Improving the Outlook for Future Generations

Since Gen X is approaching age 60, the age under investigation, the researchers can detect trends for this generation. However, with millennials (people born between 1981 and 1996) and Gen Z (people born between 1997 and 2012) more than a decade away from their oldest members turning 60, the researchers didn’t create cancer diagnosis estimates for these generations. However, if current trends remain steady, millennials and Gen Z could also see devastatingly high rates of cancer diagnoses. For some forms of cancer, like colorectal cancer, rates are already on the rise among young adults. In fact, concerns around the surging rates of colorectal cancer prompted a change in colon cancer screening guidelines, from age 50 to 45 for average-risk adults.

According to the National Cancer Institute, the chief limitation of the study is that “the conclusions are projections derived from modeling.” And, subsequently, “additional analyses in other US as well as global cancer registries are needed to tease out any geographic or other nuances in these data.”

To fill existing data gaps, the National Cancer Institute has announced a new study, the Connect for Cancer Prevention Study (Connect). The Connect study is recruiting 200,000 people between 30 and 70 years old who have no personal history with invasive cancer. The study will collect information about several different aspects of their lives and track cancer incidence among them.

These research groups have begun making strides, but we need more studies to shed light on preventive measures. We need improved clinical trial participation for medically underserved and underrecognized populations, including Black and Latinx communities and women. More targeted research studies addressing the specific concerns of marginalized groups, like the American Cancer Society’s VOICES of Black Women Study, are also urgently needed.

To lower cancer incidence in younger generations, we need greater advocacy for healthier environments, greater access to needed resources, and improved healthcare.

Since the cancer rates for Gen X are based on projections, we still have time to change their outlook—and that of the generations to come—for the better.