It has become increasingly clear that traditional governance models are inadequate to effectively respond to the challenges faced by many nonprofits and their communities. Yet most nonprofits and capacity builders continue to rely on these models, hoping that more training or improved performance will transform the way their organizations are governed, only to find that the underlying problems remain. In response to the need for new approaches to governance, a national network of practioners and researchers known as the Engagement Governance Project, sponsored by the Alliance for Nonprofit Management, has developed a new governance framework.1 Since NPQ’s last two articles on the subject, in 2006 and 2007, the Engagement Governance Project has continued to develop the framework and has launched a national participatory action research project with pilot organizations from around the country.2 The research has produced some exciting results.

Traditional governance approaches, based on corporate models and outdated, top-down “command and control” paradigms, still dominate the nonprofit sector. Within these models are strong, inherent demarcations between board, constituents, stakeholders, and staff, with the executive director often the only link between the various parts of the organization. This type of separation commonly results in the disconnection of the board and, ultimately, the organization from the very communities they serve, and it inhibits effective governance and accountability. Moreover, the pervasive trend toward “professionalism,” with boards comprised of “experts” who may or may not be engaged with the organization’s mission, has tended to deepen a class divide between boards and their communities. Ultimately, these models prevent nonprofits from being effective—that is, responsive and accountable to the communities they serve.

The Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework’s Benefits to Sustainability

NPQ: Particularly in these times, when time and organizational energy are at a premium, why would an organization choose to invest so much in a new and obviously time-intensive governance structure?

Judy Freiwirth: Well, let me use an example. One of the groups using the Community-Engagement Governance™ framework deals with homelessness issues, and their view is that having their key stakeholders involved in the governance decisions has helped their credibility with foundations, since many of the foundations they deal with are interested in their ability to exhibit a real grass-roots base. They believe that their success in foundation and individual donor funding is a direct result of engaging their key stakeholders in decision making. Having constituent leaders not only on their board but also included in meaningful governance decision making beyond the board—i.e., transcending tokenism—exhibits a strong vote of confidence toward the community being served. When constituents and key stakeholders are involved in decision making, they can be involved in visits to funders, they can testify with confidence at legislative hearings, and can be the leaders in advocacy efforts. Providing avenues for constituents and stakeholders to involve themselves in decision making means that you have many articulate advocates out there all the time, and that builds organizational reputation and raises its visibility.

NPQ: More and more people are talking about the value of networks in getting the outcomes their missions speak to. Can you talk about what this form of governance does to facilitate collaborations?

JF: If their constituents and key stakeholders are now much more involved, they’re already collaborating within the organization. The board has opened up the boundaries so the organization is more inclusive. That makes it a much more natural process to expand beyond the borders of the organization to other organizations. And, there are also more people now capable of making these connections. In the traditional organization, it’s generally the executive director, and in some cases the board chair, who develops the collaborations. Now, there are many more people with the ability and authority to go out and cultivate those relationships, as opposed to a traditional organization, where no one else has the authority.

NPQ: I recently read a piece in the New York Times that reported on museums using social media to involve their audience more closely, not just in looking but in creating. How do you think this strategy aligns with the possibilities opened up by social media?

JF: I think there is a natural synergy there that has immense potential. We are promoting an inclusive governance culture that perfectly aligns with the community engagement possibilities of social media. You can reach out to people more often with information and invite them to engage in governance decision making in multiple ways, and this allows for more adaptability in the system. We are only just beginning to see what can be done.

Beth Kanter and Allison Fine, in their new book The Networked Nonprofit, describe the normative state of many nonprofits as “fortressed organizations” that “sit behind high walls and drawn shades, holding the outside world at bay to keep secrets in and invaders out.”3 Unfortunately, this description applies to many nonprofit boards that follow traditional, insular governance models. Boards that adopt these models often become so inwardly focused that they isolate themselves from the communities they ostensibly serve.

Perhaps most important, the nonprofit sector should foster and advance democracy and self-determination. If a nonprofit organization is to be truly accountable to its community and constituencies, democracy must be at its core. Yet, the nonprofit sector has typically tended to replicate structures and processes that actually hinder democracy within organizations. Hierarchical structures in governance not only run counter to democratic values and ideals, they often impede an organization’s efforts to achieve its goals and fulfill its mission. If those who are directly affected by an organization’s actions—its constituency—are not included in key decision-making processes, they may not be as likely to back the organization with their advocacy voices, volunteer time, or cash. Additionally, a nonprofit without such involvement risks arriving at conclusions or decisions that are incongruent both to its constituents’ needs and its own mission.

Community-Engagement Governance™ is an expanded approach to governance, built on participatory principles, that moves beyond the board of directors as the sole locus of governance. It is a framework in which responsibility for governance is shared across the organization, including the organization’s key stakeholders: its constituents and community, staff, and the board. Community-Engagement Governance™ is based on established principles of participatory democracy, self-determination, genuine partnership, and community-level decision making.

The Community-Engagement Governance™ framework helps organizations and networks to become more responsive to their constituents’ and communities’ needs and more adaptive to the changing environment. It also provides more person power and credibility with funders. Because no one governance model can fit all organizations, and because many factors—including mission, constituency, stage of organizational development, and adaptability—influence what design will be most effective, the framework can be customized by each organization.4 The framework was designed as an approach, rather than a model;? this means it can be adapted to each organization’s unique needs and circumstances. In other words, while the framework is based on a common set of underlying principles, the specific structures and processes it engenders differ across organizations.

Community impact at the core. In contrast to traditional governance models, in which the primary focus is the effectiveness of the organization, the framework situates the desired community impact at its core. This reprioritizes results over institution, and also makes the desired impact overwhelmingly the most important focus of nonprofit governance.

Governance as a function, rather than a structure;? no longer located solely within the confines of the board’s structure. The Engagement Governance Project defines governance as “the provision of guidance and direction to a nonprofit organization, so that it fulfills its vision and reflects its core values while maintaining accountability and fulfilling its responsibilities to the community, its constituents, and the government with which it functions.” Legally, there are few requirements regarding who can partner with the board in shared decision making. Thus, nonprofits have leeway regarding which decisions it can choose to share with—or delegate to—constituents and other stakeholders (or share with other nonprofits), and which decisions fall under the board’s purview.

Governance decision making and power is shared and redistributed among key stakeholders, resulting in higher-quality and better-informed governance decision making and mutual accountability. The heart of governance is decision making—meaning power, control, authority, and influence. With the framework, decision making—and thus power—is redistributed and shared, creating joint ownership, empowerment, and mutual accountability. Those who have the biggest stake in the mission and are closest to the organization’s work—constituents, other stakeholders, and staff—are partners with the board in governance decision making. This redistribution of power makes nonprofits both more resilient and more responsive to their communities.

Democracy and self-determination, rather than dependency and disempowerment. The nonprofit sector should above all foster and advance democracy and self-determination, and this drive should reach deeper than simply advocating for such democratic values outside the organization. Yet most nonprofit governance models, even those that are constituent-based or “representational,” tend to replicate outdated hierarchical structures and processes. Such hierarchical structures not only run counter to democratic values and ideals, they also often impede an organization’s ability to achieve its own mission.

No one right model: an underlying contingency approach. Although the framework utilizes common principles, the specific governance structures and processes employed by a nonprofit will differ according to the organization’s needs, size, mission, and stage of development, among other variables. This results in great variability in governance designs across organizations.

Governance functions distributed creatively among stakeholders. Rather than focusing on the commonly used list of governance roles and responsibilities, it is more useful to focus first on governance functions, such as planning, evaluation, advocacy, and fiduciary concerns, and then look creatively at how these can be distributed among stakeholders.

Transparency, open systems, and good informational flow between stakeholder groups. The spread of social media and e-governance throughout the nonprofit sector is already affecting the levels of transparency within organizations. Ongoing communication and continual information flow among stakeholder groups are critical for engaging stakeholders in shared governance. Social media and e-governance have proven to be extraordinarily useful tools for creating increased transparency and facilitating large-group decision making.

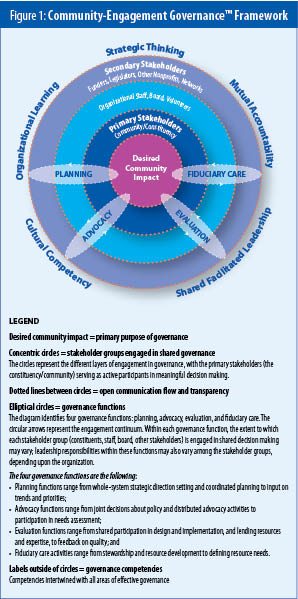

As depicted in the diagram at right, the framework allows for different kinds of shared governance to be shared among three organizational layers nonprofits serve:? (1) the primary stakeholders (i.e., constituents and those that directly benefit from the organization’s mission);? (2) the organizational board, staff, and volunteers;? and (3) the secondary stakeholders (i.e. funders, community leaders, legislators, collaborating nonprofits and partners, and networks). The organization determines, along a continuum, what types of governance decisions are situated in what layer of an organization, who should be involved in the decision as mutual participants, and how the decisions are made. Four of the key governance functions (planning, evaluation, advocacy, and fiduciary care) involve different layers of the organizational system (see Figure 1, opposite page). Policy changes, for example, might first be discussed within groups representing the interests of one layer, and then by the organization as a whole;? or, in very large organizations, within a cross-sectional group made up of representatives from each sector. Team structures that possess decision-making authority are often used as vehicles to engage stakeholders as well as “whole system” methodologies for major decisions, where all layers of stakeholders are brought together for shared decision making. And key strategic directions are usually decided on by all layers, including active constituents, other key stakeholders, and the board and staff.

We believe certain competencies are necessary for an effective shared-governance system. As shown outside the concentric circles in the diagram, there are five critical governance competencies: strategic thinking;? mutual accountability;? shared facilitated leadership;? cultural competency;? and organizational learning. These competencies should be intertwined with all areas of governance work and organizational components. In this way, they will contribute to the organization’s flexibility, adaptability, and responsiveness to environmental changes.

The design/?coordinating function of the process is performed by a design or coordinating team, or, in some cases, by the board itself. In many instances, the board continues to hold the “fiduciary care” role—ensuring financial management and resource development functions—while in others, parts of this function are shared by various stakeholders.

Nine diverse organizations are currently piloting the Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework and adapting it to their constituencies, missions, stages of development, strategic directions, and external factors. These nine organizations have a wide range of missions, annual budgets, developmental stages, constituencies and types of communities served, adaptive capacities, and staff sizes. They include national, statewide, and community-based organizations, coalitions, and networks. Their missions include immigrant rights and services, homelessness prevention, affordable housing advocacy and services, national policy education, reducing disparities in health access, obesity prevention, youth development, community organizing, and leadership development.

One pilot is being conducted by a network/?partnership of more than 100 nonprofit organizations and state agencies. Using the Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework, this network has developed a statewide shared governance structure with the purpose of fighting obesity and chronic disease in the state. Another pilot is being conducted by a “reinvented” organization that had been dormant for five years. The organization, which focuses on youth development through mentoring with seniors, is now using the framework to make itself more responsive to the community and more effective in implementing its mission.

The consulting/?research team has been using action research methodology—a systematic cyclical method of “planning, taking action, observing, evaluating, and critical reflecting prior to continued planning”—to document findings for continual learning.5 Each pilot organization is either currently working or has worked with a lead consultant from the Community-Engagement Governance™ team. With the participating organizations, the consulting/?research team is documenting the process by conducting a series of semi-structured interviews and surveys with a cross section of primary and secondary stakeholders. Together, we are learning about the implications of different variations of the approach;? the benefits and challenges for the organizations, networks, and communities;? the success factors;? and how to improve the framework.

The consultants have assisted the pilot organizations with different governance designs (structures and processes). Each organization determines which decisions will be shared by which stakeholder groups, and how such decisions will be made and coordinated. Some pilot organizations have created structures that include cross-representational decision-making teams and task forces focused on specific governance functions, such as strategic direction setting, planning, advocacy, and fiduciary oversight. Most of the pilots have also used large-group decision-making methodologies, such as World Café, Future Search, and Open Space Technology.6 Pilot organizations have used community forums, town hall structures, and other large-group democratic meeting formats, too. For example, one pilot organization convenes a members assembly several times a year to decide on its strategy;? this assembly includes active members, key community leaders, and the board and staff.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Another pilot organization convenes large-group “visioning sessions,” which set the strategic and advocacy direction for the year. These sessions involve a large group of constituents, the board, staff, member organizations, and other collaborating organizations. Other pilot organizations have used e-governance and social media, not only to facilitate shared leadership through transparent information, but also to facilitate ongoing strategic-level discussions, and, most important, to make decisions as a large group. In addition, pilot organizations have used “open system,” team decision-making structures.

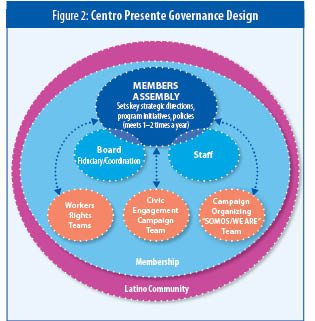

Centro Presente, a prominent immigrant rights organization in Massachusetts, shares governance functions—such as decisions regarding strategic planning /?setting, strategic directions, executive-director hiring, campaign planning, advocacy and organizing, and leadership development—with their members (who come from their broader, Latino, community). The board continues to hold fiduciary and legal responsibilities but shares most other key decisions with the membership. Member assemblies are convened several times a year, and are the highest decision-making structures for the organization. At the assemblies, a large group of active members from the community, board, and staff jointly make the larger strategic-direction decisions for the organization. They also delegate governance responsibility through a team structure. These teams, which assume much of the governance decision making focused on program directions and campaign organization, comprise the board, staff, and active members.

Centro Presente, a prominent immigrant rights organization in Massachusetts, shares governance functions—such as decisions regarding strategic planning /?setting, strategic directions, executive-director hiring, campaign planning, advocacy and organizing, and leadership development—with their members (who come from their broader, Latino, community). The board continues to hold fiduciary and legal responsibilities but shares most other key decisions with the membership. Member assemblies are convened several times a year, and are the highest decision-making structures for the organization. At the assemblies, a large group of active members from the community, board, and staff jointly make the larger strategic-direction decisions for the organization. They also delegate governance responsibility through a team structure. These teams, which assume much of the governance decision making focused on program directions and campaign organization, comprise the board, staff, and active members.

Homes for Families, a statewide organization that serves the homeless, holds a “whole-system” yearly visioning session that involves constituents, board, staff, members, and partner organizations. During the session, the strategic directions and new initiatives for the organization are decided on together. Based on these decisions, the board (half constituents, half other primary stakeholders) and teams (also comprised of constituents and primary and secondary stakeholders) coordinate a range of governance decisions. Uniquely, they have developed an integrated, ongoing constituent leadership development program that builds governance skills—especially advocacy skills, which are significant for their mission. Constituents who “graduate” from the training assume leadership positions within an advocacy leadership team, which then designs and implements their advocacy/?organizing strategy. Constituents and other stakeholders also comprise the public policy committee, which makes governance decisions regarding public policy strategy between visioning sessions. Some constituent leaders are also board members, and contribute to other governance decisions. In addition, to address other governance decisions, the organization currently plans to develop new cross-sectional teams comprising representatives from each organizational layer.

Homes for Families, a statewide organization that serves the homeless, holds a “whole-system” yearly visioning session that involves constituents, board, staff, members, and partner organizations. During the session, the strategic directions and new initiatives for the organization are decided on together. Based on these decisions, the board (half constituents, half other primary stakeholders) and teams (also comprised of constituents and primary and secondary stakeholders) coordinate a range of governance decisions. Uniquely, they have developed an integrated, ongoing constituent leadership development program that builds governance skills—especially advocacy skills, which are significant for their mission. Constituents who “graduate” from the training assume leadership positions within an advocacy leadership team, which then designs and implements their advocacy/?organizing strategy. Constituents and other stakeholders also comprise the public policy committee, which makes governance decisions regarding public policy strategy between visioning sessions. Some constituent leaders are also board members, and contribute to other governance decisions. In addition, to address other governance decisions, the organization currently plans to develop new cross-sectional teams comprising representatives from each organizational layer.

Shaping New Jersey, a statewide network of more than 100 nonprofit and government organizations, is using this framework for a coordinated planning and implementation process to reduce New Jersey’s obesity levels. Using the Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework principles of shared governance and power, network members have designed a structure and process in which the partner organizations make governance decisions regarding the planning and implementation of state-level environmental and policy strategies. An executive/?sustainability committee representing fifteen to twenty partner organizations serves as both a design and coordination team. The team facilitates meaningful partner engagement in joint advocacy, communication, and collaborative plan implementation. While full partnership meetings occur twice a year, most of the decision making occurs within a variety of work teams comprised of partner organizations empowered to make decisions ranging from setting advocacy priorities to designing strategies for increasing access to healthful foods. They also employ e-governance, using polling to make decisions and a web portal to make documents and reports transparent to the full partnership.

Shaping New Jersey, a statewide network of more than 100 nonprofit and government organizations, is using this framework for a coordinated planning and implementation process to reduce New Jersey’s obesity levels. Using the Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework principles of shared governance and power, network members have designed a structure and process in which the partner organizations make governance decisions regarding the planning and implementation of state-level environmental and policy strategies. An executive/?sustainability committee representing fifteen to twenty partner organizations serves as both a design and coordination team. The team facilitates meaningful partner engagement in joint advocacy, communication, and collaborative plan implementation. While full partnership meetings occur twice a year, most of the decision making occurs within a variety of work teams comprised of partner organizations empowered to make decisions ranging from setting advocacy priorities to designing strategies for increasing access to healthful foods. They also employ e-governance, using polling to make decisions and a web portal to make documents and reports transparent to the full partnership.

Although the action research continues, several significant preliminary findings illustrate the benefits of the framework’s approach:

1. Increased ability to respond to community needs and changes in environment;? increased accountability to the community.

All the pilot organizations that have implemented a significant portion of their new governance model report that through the process of involving their stakeholders in governance decisions, they have been able to respond more quickly to changes in their environment, be more responsive to community needs, and to mobilize more quickly in response. For example, Centro Presente felt that by redistributing power in their organization so that it was shared between the board and their active membership (community members who are directly affected by immigration policy changes), they could mobilize much more quickly in response to immigration policy changes. Similarly, other pilot organizations report that they have been more proactive, adaptable, and nimble in their decision making. With stakeholders having a significant role in decision making, the pilot organizations believe their accountability to the community has also increased.

In the past, Shaping New Jersey had attempted to develop a coordinated plan of action, but they were unable to create enough ownership of the plan to lead to its successful implementation. Now, through the use of the Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework, they have created a process and structure of shared governance, resulting in a highly collaborative, coordinated (“owned”) plan. The group rates a sense of shared ownership and accountability to the larger community as a critical factor in achieving successful outcomes. They also report that this sense of ownership and a new, high level of participation in decision making from the more than 100 partners have resulted in a coordinated action plan that responds to the alarming rate of obesity in their state.

2. Improved quality and efficiency of governance decision making: increased strategic thinking, creativity, and problem-solving ability.

Pilot organizations that have implemented the framework state that the quality of their governance decision making has improved as a result of their shared governance model. They cite increased creativity along with new thinking and innovative ideas, all resulting from the involvement of key stakeholders in their decision making. Others point to the ability to be more strategic in discussions;? with more community involvement, they are better able to solve complex problems. For example, one pilot organization cites its ability to design a compelling and effective strategy in its lobbying efforts with legislators. Subsequent discussions and strategic decisions made with their primary stakeholders—currently and formerly homeless individuals—led to a much more effective and creative organizing and lobbying strategy. This, in turn, led to increased government funding for more innovative and responsive services. Another pilot organization spoke of its increased ability to quickly align its program direction with changing community needs.

One frequently asked question about the framework is whether involving stakeholders in the decision-making processes leads to more cumbersome, time-consuming processes. The answer appears to be no. In fact, the pilot organizations report that, compared with their previous models, they are now able to make more efficient decisions by using a shared governance structure. By including key stakeholders in the decision-making process, the information, knowledge, skills, experience, and connection to the mission are “in the room and more accessible to the decision-making process,” thereby allowing organizations to make effective decisions more quickly.

3. Increased shared ownership of the organization’s mission and strategic directions.

Pilot organizations report that implementing a shared decision-making structure—one that includes stakeholders—leads to increased investment and ownership of those decisions. Others report that the quality of those decisions has dramatically improved. Still others cite an increase in morale among both the board and staff.

4. An increase in new and more distributed leadership.

As part of their efforts to include community members and constituents in shared governance decision making, some pilot organizations report that they have developed leadership-development initiatives to assist constituents in acquiring leadership skills. In the past, these initiatives tended to include leadership-development workshops, but now constituents are more likely to be engaged in “learning by doing,” often sharing leadership of work teams, task forces, and other decision-making structures.

5. Improved ability to engage in deep collaboration with other nonprofits.

Pilot organizations report that by removing the boundaries around the board and engaging stakeholders in decision making, they can develop new, deeper collaborations. In some cases, this has resulted in “networked governance”—joint governance decisions across numerous organizations.

6. Increased visibility within the broader community.

Several groups report that their increased ability to respond to changes and needs in the community has led to more ongoing and increased visibility within their communities. In turn, this increased visibility has led to greater support from secondary stakeholders, and, ultimately, has helped to build their membership and network of supporters.

7. Increased fundraising capacity and sustainability.

Several pilot organizations report that their increased visibility—through the process of engaging their community in governance decision making—has strengthened their fundraising. As they shifted to a grass-roots fundraising strategy that engaged community members, they eventually built more diverse community ownership of the organization, as well as more sustained funding.

8. Increased transparency and community ownership and more effective large-group decision making through the use of social media and web portals.

Several pilot organizations have used social media and web portals, including tools for large-group decision making, on a regular basis. They have found that these tools increase the group’s transparency, facilitate inclusive decision making, and build mutual accountability.

9. Boards that are more engaged, passionate, and transparent about their organization’s strategic direction and programs.

Pilot organizations report that as a result of their new governance model, their boards have become much more engaged in their work and more passionate about their organization’s strategic direction and programs. As boards worked more closely with stakeholders, especially constituents and key community leaders, they developed a more meaningful relationship with the community and a deeper understanding of the community’s needs. The amount of transparency among the board, staff, and other stakeholders also increased. Those organizations that used social media and e-governance modalities also reported a significant increase in transparency and, ultimately, accountability to their communities.

The action research also reveals that for many organizations, the identity of their constituents, community, and primary stakeholders is often unclear. Establishing a shared understanding of who their stakeholders are seems to be a key success factor. Also, an organizational champion with authority (usually the executive director or board chair) is ultimately needed to help lead the process. Depending on their new governance structure, some pilot organizations have successfully included their staff in governance decision making, especially when the staff represented the organization’s constituency. The success of staff involvement depends on the organizations culture and mission. Another success factor is the creation of a cross-sectional design or coordinating teams to help design the new governance model for the organization.

Although this governance framework demonstrates promising benefits, the level of change needed can be difficult for some organizations. Initially, boards need to be willing to try new, innovative frameworks and practices, a challenge for many boards. Many organizations are reluctant to engage in the uncertainty and ambiguity that often accompany transformation. Moreover, many boards will need to dramatically shift their perceptions of constituents—from a “charity”/?deficit perspective to one of constituents as invaluable assets for the organizations success. Sharing power—both the concept and its implications—is perhaps the biggest hurdle for any board.

Although we continue to learn from our experience and research, the Community-Engagement Governance™ Framework demonstrates promising benefits for nonprofits and their communities. We continue to look forward to feedback from NPQ’s readership, and seek additional organizations that would like to join this learning community and help advance the governance field. We hope this new framework will not only advance the movement toward more effective governance models and practices but also assist nonprofits in transforming their governance into one that is more inclusive, democratic, and, ultimately, more focused on impacting the communities they serve.

The author would like to acknowledge the work of the many members of the Alliance for Nonprofit Management’s Engagement Governance Project/?Governance Affinity Group, who have worked consistently over the past few years helping to shape this framework; Regina Podhorin, for her work with one of the pilot organizations; and Maria Elena Letona, for her invaluable assistance with developing the framework and this article.

- The Alliance for Nonprofit Management is the premier national organization of capacity builders. www.Allianceonline.org

- Judy Freiwirth, “Engagement Governance for System-Wide Decision Making,” The Nonprofit Quarterly, summer 2007, 38-39;? Judy Freiwirth and Maria Elena Letona, “System-Wide Governance for Community Empowerment,” The Nonprofit Quarterly, winter 2006, 24-27.

- Beth Kanter and Allison Fine, The Networked Nonprofit: Connecting with Social Media to Drive Change. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons, 2010.

- Patricia Bradshaw, “A Contingency Approach to Nonprofit Governance,” Nonprofit Management & Leadership, vol. 20, no. 1, 2009, 61-81.

- Rory O’Brien, “An Overview of the Methodological Approach of Action Research,” 1998 (https://www.web.net/~robrien/papers/arfinal.html).

- Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff, Future Search: Getting the Whole System in the Room for Vision, Commitment, and Action. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2010;? Juanita Brown, The World Café: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter, San Francisco, 2005;? Harrison Owen. Open Space Technology: A Users’ Guide. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1997.