December 10, 2019; ProPublica

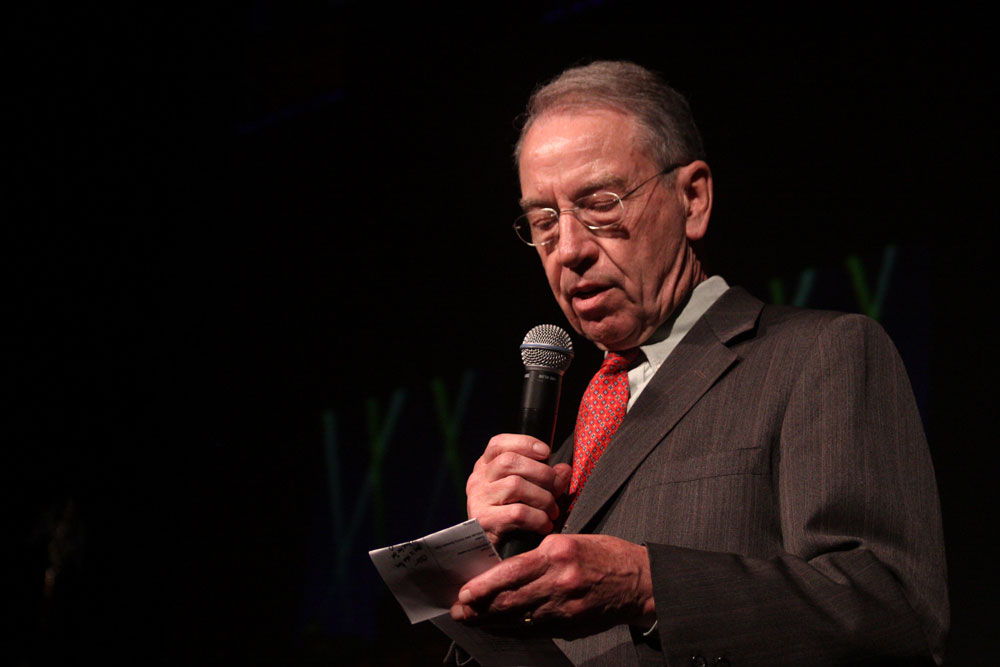

Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA), chair of the US Senate Finance Committee, has sent a letter to the largest health care system in Memphis, Tennessee, asking for an explanation of the its debt collection practices. Methodist Le Bonheur, a nonprofit, faith-based health system was the subject of an investigative report from ProPublica and MLK50 in June 2019 that uncovered the health care system’s aggressive collection practices, which even included garnishing the wages of low-wage staff who had been patients at one of its hospitals.

Methodist Le Bonheur is only one of multiple health care providers that have come under scrutiny, as journalists at ProPublica, Kaiser Health News, and local news organizations like MLK50 have sat through hours of debt court, sifted through thousands of pages of documentation, and talked with patients who have had their wages garnished, lost their homes, and, in some cases, ended up in jail as a result of medical debt.

Grassley sent a similar letter to University of Virginia’s Health System in October, after Kaiser Health News published its investigation of how the state’s number one health system was aggressively pursuing poor and middle-class patients. That investigation found that the hospital sued 36,000 patients, with debts ranging from $13.91 to $1 million, over a six-year period.

Grassley’s pursuit of these egregious practices is commendable, but one might ask, is it “too little, too late”? As a result of the investigative reporting from ProPublica and others, both UVA and Methodist Le Bonheur announced systematic changes in their debt collection practices, long before Grassley sent his letters.

Immediately following its exposure in the news media last June, Methodist announced its decision to drop hundreds of lawsuits against patients; the health system has not filed a single suit since last summer. According to ProPublica, the hospital reduced the bills of 2,200 patients and erased the debts of over 5,000 patients.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The hospital also changed its debt collection policies, increasing the threshold for financial assistance for uninsured patients, and agreeing not to pursue debt collection for any patient living in a household with earnings below 250 percent of the poverty level.

UVA has also changed its practices. As reported in NPQ in September 2019:

Under UVA Health’s new policy, families with incomes up to 400 percent of the poverty level ($103,000 for a family of four) will now be eligible for financial aid, while the previous threshold was about half that. Also, families will be able to access financial assistance if their assets, beyond the value of their house and car, don’t exceed $50,000. The previous threshold was $4,000, with hospital collections often decimating the little savings a family had managed to accumulate for retirement or college.

In the letter to Methodist, Grassley acknowledged the changes the hospital system has made, but wondered about implementation. He asked, “How will Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare’s new financial assistance policy better serve low-income patients compared to its old policy beyond including more people in it?”

Grassley has long been concerned with nonprofit practices, particularly in health care. Nonprofit hospitals, which do not pay taxes, are required to provide charitable care, but many continue to bill those who cannot afford to pay. Methodist Le Bonheur offered discounted and free care to uninsured patients but pursued underinsured patients with large deductibles and copays relentlessly. It may be time to move beyond letters and put in place policies that put an end to this misery for millions of Americans who must add the stress of debtors’ courts and prisons to the stress of serious illness.—Karen Kahn