Editors’ note: This article is from Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine’s winter 2023 issue, “Love as Social Order: How Do We Build a World Based in Love?”

Imagine a civil society in which communities, individuals, and leaders (nonprofit, social movement, philanthropy, business, education, and more) regularly engage in the process of self-examination for the sake of improving our world.

The Archaeology of Self, a pivotal component of the six-step Racial Literacy Development Model (or RLDM) that I developed in 2018, offers an avenue for personal and collective healing via self-examination. This component provides a process for delving deeply into one’s own life experiences and peeling back the layers to uncover the complex dynamics—specifically of race and diversity—that shape our perspectives. Engaging in such self-excavation—by which individuals learn to confront their beliefs and biases—is crucial for creating and maintaining a more inclusive, just, and healthy civil society.

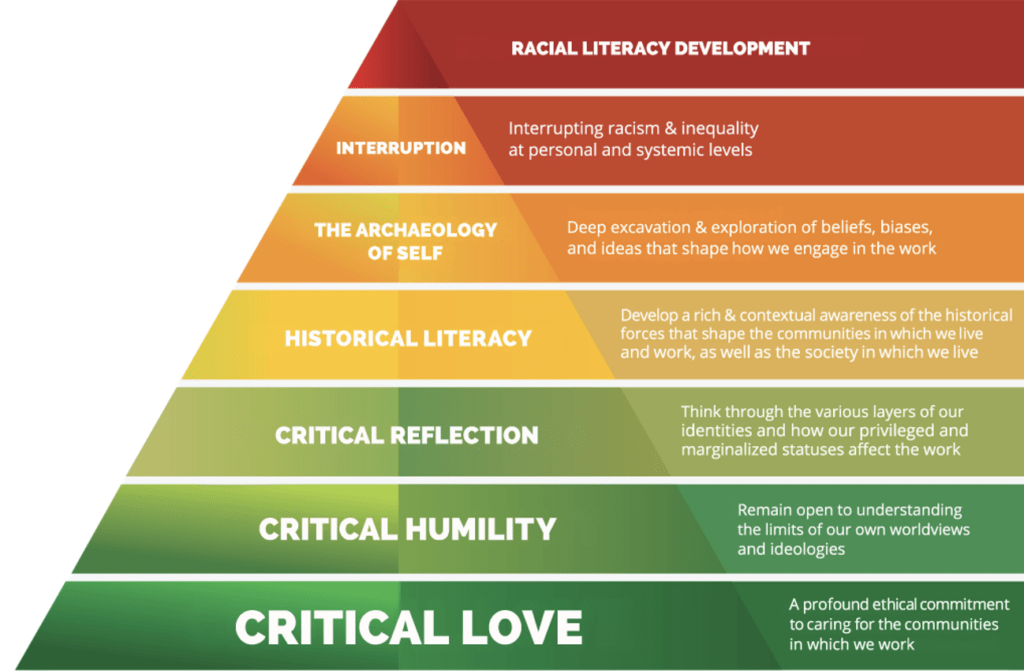

The Racial Literacy Development Model is an action-oriented process toward eradicating one’s own racial bias with the goal of changing systems governed by racism and inequality.

I highlight this component because it fosters practicing the personal reflection, self-examination, self-discovery, and growth that are required for societal change. The work of combating racism is a lifelong journey. It requires that citizens provoke the growth and progression of society through examination of the policies and laws that impact their lives. The Archaeology of Self step of the RLDM practice helps individuals to guide themselves and others toward specific steps needed at the local (self) level before they move on to working on the global (society) level—because by first addressing and working toward eliminating racism from personal belief systems, individuals can then help to dismantle the systemic racism that permeates civil society.

Racial Literacy for (an Improved) Civil Society: The Racial Literacy Development Model

An active civil society forms the bedrock of a robust democracy. Throughout history, the United States has witnessed numerous instances when citizens’ actions and engagement have reshaped governance and influenced the course of the nation. Civil society leaders must grapple with complex challenges rooted in social inequality, systemic biases, and cultural divides. These leaders face the uphill task of fostering inclusive environments, advocating for justice, and addressing deep-seated issues of racism and discrimination.

The Racial Literacy Development Model (see Figure 1) is an action-oriented process toward eradicating one’s own racial bias with the goal of changing systems governed by racism and inequality. It provides a structured framework for individuals to engage in deep self-reflection and skill building by encouraging a continuous process of self-examination, learning, and advocacy to address systemic injustices. The model empowers individuals to reflect on their own assumptions, engage in constructive conversations, challenge prejudices, and actively work toward creating more inclusive and equitable spaces. The process requires love, humility, reflection, an understanding of history, and a commitment to working against racial injustice. People who engage in personal reflection about their own racial beliefs and practices—and develop racial literacy in so doing—are then able to guide others to do the same.

Racial literacy development is a powerful tool for those wanting to sincerely engage in efforts that promote equity and justice. Racial literacy empowers civil society leaders to be more empathetic, responsive, and effective in their roles. It equips them with the necessary tools for addressing systemic issues, advocating for marginalized communities, and working toward a more equitable and just society. Racially literate leaders can uphold the values of a civil society by implementing policies and practices that are culturally responsive and inclusive—ensuring that the services, opportunities, and resources they provide cater to the diverse needs of a diverse population.

There are three tenets and six interconnected components to the RLDM. These are designed to facilitate a layered and comprehensive understanding of racial dynamics and promote active engagement in dismantling biases and inequities.

The three tenets are: question assumptions, engage in critical conversations, and practice reflexivity.

Recognizing that it is necessary to hold oneself and one’s peers and colleagues accountable for confronting and challenging personal and systemic biases is crucial.

Questioning one’s assumptions about race—acknowledging one’s biases and taking the stance that much of what one assumes to know about race is faulty and incomplete—is fundamental to racial literacy development. In questioning their own assumptions about race, individuals are taking a stance that will foster active resistance to the racist and discriminatory beliefs, practices, and policies they encounter in their environment.

Engaging in critical conversations is an essential next step. The RLDM helps individuals to develop the confidence to discuss their assumptions and those of others.

Practicing reflexivity is a cyclical process of regularly reexamining perceptions, beliefs, and actions. This is a crucial step in racial literacy development, because this work is necessarily ongoing and will evolve or shift along with shifts in the environment.

The six components are as follows:

- Critical Love, which focuses on fostering deep commitment and ethical responsibility toward communities. For example, in education, critical love prompts teachers to reflect on their approach to teaching, ensuring that they prioritize not just academic success but also love and support for their

- Critical Humility, which is the willingness to acknowledge the limitations of one’s own viewpoints and ideologies. Critical humility involves embracing a mindset of continuous learning, recognizing that our perspectives are shaped by our experiences and may not encompass the full breadth of understanding. Embracing critical humility allows us to be receptive to new knowledge, diverse viewpoints, and alternative narratives, fostering empathy and openness in our interactions.

- Critical Reflection, which involves a deep introspection vis-à-vis our identities, acknowledging both our privileges and our marginalized Critical reflection is about recognizing how these identities intersect and influence our perspectives and experiences. Through critical reflection, we can understand our own biases and assumptions, allowing us to navigate interactions more consciously and empathetically.

- Historical Literacy, which involves understanding the historical context of society and communities. In schools, for example, historical literacy equips educators with the knowledge they need to engage respectfully with their students and parent communities. It also provides an approach to addressing historical injustices.

- The Archaeology of Self, which encourages individuals to embrace self-reflection and self-discovery toward the action of becoming conscious of and evolving away from preconceived notions and biases. The Archaeology of Self allows for a more open-minded and inclusive approach to working and living in society.

- Interruption, which is the active process of confronting and challenging racism, biases, and other Through the lens of racial literacy, this action can and should occur on both personal and systemic levels. Interruption involves speaking up and taking action to disrupt harmful patterns or behaviors that perpetuate discrimination. This can range from addressing microaggressions in personal interactions and providing microvalidations1 to advocating for policy changes to dismantle systemic inequities.

Recognizing that it is necessary to hold oneself and one’s peers and colleagues accountable for confronting and challenging personal and systemic biases is crucial. This accountability helps to ensure that the principles and practices of racial literacy are actively integrated into whatever setting is the focus, creating more inclusive and just environments.

“Know Thyself”: An Approach for Today’s Times

Social justice work requires a consistent willingness to take risks for the betterment of others. As long as we are alive, we are continually discovering who we are and to what lengths we are willing to go in the pursuit of justice. The Archaeology of Self is an invaluable tool in this ongoing quest. It recognizes that a personal reckoning must occur before any individual can effectively champion social justice causes in society. Knowing oneself is essential for maintaining commitment to the cause of social justice; it ensures that our actions and advocacy are driven by genuine conviction rather than performance for others.

This introspective journey fosters wellbeing, in that contributing to creating a socially just world leads to enhanced self-awareness, empathy, and better relationships—all of which support overall health.

The essence of working with this component lies in recognizing the influences that have shaped us throughout our lives, including our families, cultures, and society. It is crucial to pause and consider the extent of these influences, which often go unnoticed. Without this introspection, we might act reactively, without fully comprehending the foundation of our behaviors or perceptions of others. Self-examination should be the fundamental basis for approaching any endeavor that involves social justice; understanding one’s identity in relation to others is critical for effective service.

As we consider the Archaeology of Self process, it is important first to discuss the perceived and actual obstacles preventing people from engaging in an archaeological dig around their biases and stereotypes. The process of the Archaeology of Self as it relates to racial healing is intricately connected to wellbeing precisely because it helps individuals overcome these obstacles and promotes personal growth, a healthy racial consciousness, and deeper self-awareness. Some obstacles include the following:

- Fear and discomfort: Many people are afraid to confront their biases and stereotypes because this can be uncomfortable and unsettling. It can bring to light deeply ingrained beliefs that challenge one’s self-image.

- Denial: Due to fear or discomfort, some individuals may deny the existence of their biases and stereotypes, preferring to believe that they are entirely unbiased and open-minded. Avoidance of deep self-examination of biases and stereotypes can negatively impact mental and physical health by contributing to stress, cognitive dissonance (whereby individuals are grappling with the contradiction between their self-image and their actual beliefs), and strained relationships.2

- Defense mechanisms: Some individuals may become defensive when confronted with their biases, perceiving even gentle challenges to their words or actions as personal This defensiveness blocks open dialogue and self-exploration.

- Social and cultural conditioning in a civil society: Societal norms and cultural influences often perpetuate biases and stereotypes. Even in a civil society like the United States, which claims to base itself on principles of equality, people may be unwilling to challenge ingrained beliefs because they fear social isolation, closed doors regarding personal opportunities, or outright This avoidance can result in a lack of authenticity and also in inner conflict, contributing to mental stress and other health issues. (A current insidious example of this is the phenomenon of cancel culture.3)

- Lack of awareness: Some individuals simply lack awareness of their biases and They may not realize how their actions and beliefs perpetuate discrimination or harm. Ignorance in this context prevents personal growth and self-improvement.

The Archaeology of Self addresses such obstacles by providing a structured and compassionate approach to self-examination. By encouraging individuals to explore their beliefs, biases, and experiences through the power of storytelling in a nonjudgmental way, they are helped to become more aware of their own thought processes and how they contribute to societal issues. This introspective journey fosters wellbeing, in that contributing to creating a socially just world leads to enhanced self-awareness, empathy, and better relationships—all of which support overall health.

Implementing An Archaeology Of Self Program For Your Organization

If your organization wants to engage employees in Archaeology of Self work, implementing the following eight steps can help staff, in a structured and compassionate way, start their journey of self-examination—leading to improved self-awareness, empathy, and a more socially just working environment and world-at-large.

Step 1: Establish an Archaeology of Self program to educate individuals on the importance of self-examination. This can be achieved by providing workshops that offer the opportunity to address biases and stereotypes through the use of various resources—readings, videos, and conversation groups—that help them to prepare for and practice self-examination.

Step 2: Build “safe and brave” spaces, where nonjudgmental conversations, introspection, and reflection through storytelling can happen. Such spaces should be designed to encourage open dialogue and discussions in which colleagues can share their life experiences and beliefs without fear of criticism or judgment. (This is especially important right now, with the prevalence of cancel culture.4)

Step 3: Provide storytelling workshops, where participants can share their personal narratives and be encouraged to reflect on critical moments, experiences, and beliefs that shape their perspectives and decisions. These workshops should emphasize critical listening toward building empathy, understanding, and connection among participants.

Step 4: Create “excavation exercises” that prompt individuals to examine their beliefs, biases, and experiences. Exercises on the topics of race, schools, family name, and neighborhoods open opportunities for self-examination to occur. So much of our understanding of race stems from our formative years, as we are influenced by pivotal places and events in our development. That’s why I encourage people to engage in excavation activities aimed at recalling significant school memories, be they positive or negative; initial encounters with racism; and stories tied to their names. Names serve as a window into a person’s cultural, religious, or ethnic experiences, offering insight into the intersectional nature of race and other social influences shaping our beliefs. And reflecting on childhood friendships and the neighborhood in which we grew up allows us to contemplate the segregation or integration of our surroundings, revealing how our connections with others today often trace back to these early experiences.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Reflection through journaling, mindfulness practices, or guided meditation focused on exploring one’s thoughts and emotions without judgment adds to the effectiveness of these exercises, and should be encouraged. (Such exercises can also be used as prompts for Step 3, where participants share their personal narratives.)

Excavation Exercises

Race story prompt: Recall your first memory with racism—were you the perpetrator of the idea, or on the receiving end?

Name story prompt: We all have a unique connection to our name—some of us love our name, some of us hate our name, some of us simply feel that our name signifies a special family tie. This activity asks you to reflect on your own name and write a brief story about it. Remember, it’s your story: feel free to focus on your full name, middle name, last name, or even your nickname.

Neighborhood story prompt—a series of reflection questions: 1. Where were you born? 2. Where did you grow up? Describe your neighborhood. 3. Where did you attend school? (Choose a school level: for example, elementary, middle, high.) Describe your classmates. Did you perceive your teachers to be similar to or different from you and your family? In what ways were they similar or different? 4. Describe the neighborhood where your school is/was located. (If you are a teacher, you can also describe your students. Are your students similar to or different from the students when you were at school?)

Step 5: Organize facilitated discussions following storytelling and excavation exercises. The goal of these discussions is to enable participants to talk about their feelings, challenges, and insights that surfaced during the storytelling and excavation exercises. Selecting an appropriate facilitator to provide constructive feedback and guidance is essential here.

Step 6: Expect and encourage application of insights/new awareness to everyday life. Provide reflection tools that guide employees in deliberate and purposeful self-examination of their daily interactions. These tools should help them define “critical incidents,” during which they will need to address biases or stereotypes in their daily life.

An example is the critical incident reflection, which prompts individuals to be introspective about a challenging racial dialogue or experience they’ve encountered. Participants are asked to recall the incident vividly, identifying who and what circumstances were involved. They explore the factors that might have contributed to the incident, including personal, cultural, and institutional elements. Throughout this reflection, participants are asked to acknowledge their thoughts, emotions, observations, and reactions during the incident. They consider how they responded or reacted at the time. After reflecting on the incident, participants assess the impact it had on them personally and professionally. They evaluate whether the experience has influenced their current approach to engaging in dialogues on race.

This exercise opens up possibilities for a deeper understanding of one’s reactions and perceptions, and provides an opportunity to learn from challenging discussions about race, foster personal growth, and alter future approaches to similar incidents (practice of reflexivity).

Step 7: Provide support and follow-up through mentorship and counseling programs, your Employee Assistance Program (EAP), or your human resources department. Offer access to resources for deeper learning, such as recommended readings, webinars and other online events, and additional workshops and programs offered outside the organization.

Step 8: Encourage accountability and continued engagement by building Archaeology of Self work into your staff-evaluation systems. Assess the impact of the Archaeology of Self program through feedback surveys, interviews, and other qualitative assessments. Use existing assessments—such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT)5—or design your own that measure changes in participants’ self-awareness, bias reduction, empathy, and attitudes. Use these data to refine and improve the Archaeology of Self program for future implementations.

In a world grappling with profound issues of social justice, building racially (and thus socially) just local and global communities is both an ongoing moral imperative and vital to individual and collective health.

Implementing Your Own Archaeology Of Self Program

If you want to engage in Archaeology of Self work without the help of an organization, you can consider the eight modified, individualized steps below, which will guide you in fostering self-awareness and empathy and help you to contribute positively to personal and societal growth.

Step 1. Self-educate by exploring readings and videos on developing racial literacy, and finding (or forming) a conversation group to work on the principles together.

Step 2. Create a “safe and brave” personal space by mentally preparing yourself to be challenged by this work and extending grace and patience to yourself as you delve into your beliefs. Dedicate time for personal reflection and introspection without self-criticism.

Step 3. Tell your stories by reflecting on pivotal moments, experiences, and beliefs that have shaped your perspectives and decisions. Consider finding a therapist to explore these stories with you toward self-empathy, understanding, and action.

Step 4. Engage in self-examination practices by creating your own or using existing resources that provide exercises that help you to excavate your personal beliefs and biases, especially in the areas of education, family, community, and society. Reflect on your excavations through journaling, mindfulness, or guided meditation techniques.

Step 5. Practice self-facilitated discussions by initiating critical conversations with yourself about the insights you’ve gained, challenges you’ve faced, and the self-awareness that is developing through your Archaeology of Self journey. Give yourself constructive self-feedback along the journey. It may be helpful to record your self-facilitated discussions so that you can keep track of your work and progress.

Step 6. Apply your awareness during daily interactions and critical incidents you experience or that you witness between/among others. Strive for this awareness to become part of your daily practice.

Step 7. Seek help and support by looking for mentorship or counseling resources through your research or personal networks. This will provide you with enhanced support, learning, and growth. Invite a friend to join you on the journey. You can be each other’s support and keep each other accountable, periodically checking in to report on how you are progressing.

Step 8. Remain steadfast and don’t get easily discouraged or give up. Archaeology of Self work may get difficult at times, but there is so much to be gained by pushing through and keeping your commitment to ongoing self-examination and growth!

***

I created the Archaeology of Self self-excavation process and the building of personal racial literacy overall to be tools for addressing the personal and systemic societal challenges we face. In a world grappling with profound issues of social justice, building racially (and thus socially) just local and global communities is both an ongoing moral imperative and vital to individual and collective health.

Notes

- Laura Morgan Roberts, Megan Grayson, and Brook Dennard Rosser, “An Antidote to Microaggressions? Microvalidations.,” Harvard Business Review, May 15, 2023, org/2023/05/an-antidote-to-microaggressions-microvalidations.

- Robert Carter, “Race-Based Traumatic Stress,” Psychiatric Times 23, no. 14 (December 1, 2006).

- Aja Couchois Duncan and Kad Smith, “The Liberatory World We Want to Create: Loving Accountability and the Limitations of Cancel Culture,” Nonprofit Quarterly Magazine 29, 1 (Spring 2022): 112–19; and Saphia Suarez, “Who Died and Made You Judge?,” NPQ, October 12, 2023, nonprofitquarterly.org/who-died-and-made-you-judge/.

- Ibid.

- Project Implicit, “About the IAT,” accessed December 4, 2023, harvard.edu/implicit/iatdetails.html.