This article is the third in a series of articles that NPQ, in partnership with First Nations Development Institute (First Nations), will publish in the coming weeks. The series will highlight leading economic justice work in Indian Country and identify ways that philanthropy might more effectively support these efforts.

The confluence of a devastating global pandemic, climate crisis, and a racial justice reckoning in the US has forced political, business, and community leaders alike to question the systems and structures that got us to this point. Native communities—and Native entrepreneurs in particular—offer solutions for where we need to go.

Native entrepreneurship is typically underpinned by a philosophy and values that emphasize living in beauty, balance, and harmony. In Navajo, this concept is called Hózhó. Many other tribal nations have similar concepts. To live outside your means is an imbalance. Growing your herd of cattle and overgrazing your land is not harmonious with the Earth’s natural order. Similarly, the “growth at all costs” mindset of modern business is incompatible with Hózhó.

Successful Navajo businessmen and women build enterprises that sustain, nurture, and regenerate their communities and the natural ecosystems around them.

We see elements of Hózhó increasingly showing up in mainstream business and policymaking. These movements go by many names, including social enterprise, impact investing, community-driven finance, sustainable economic development, and the “doughnut economics” model that Amsterdam in the Netherlands is now championing.

This global shift is promising. But such ways of doing business still are not the norm. Native business owners and their communities suffer disproportionately as a result.

Change Labs, the nonprofit I direct, has worked to support Native American entrepreneurs across the Southwest by providing business acceleration programs and services for the past six years, with a vision to unlock entrepreneurship as a tool for sustainable economic growth and poverty alleviation. The entrepreneurs advance that vision through fashion design, healthcare, farming, artisanal beauty products, and more. All are fiercely committed to creating livelihoods that center community well-being.

But being a Native entrepreneur comes with a unique set of challenges—ones that too often stifle the promise and potential of business solutions by and for tribal communities. Many of these challenges stem from centuries of policymaking designed to exclude, oppress, and deprive Native people of wealth and resources. Others are the result of unrealistic or misaligned expectations from Native-run businesses.

Combined, these issues cause US tribal lands to be among the hardest places to do business in the world.

The Cost of Unsupported Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship in Native communities is widespread, but formalized entrepreneurial ecosystems are grossly inadequate. At least half of self-made Native businessmen and women operate in the informal sector, selling homemade foods, artisanal crafts, and artwork out of economic necessity. Many of these informal businesses have real promise to support their local communities, but they lack the infrastructure, tools, and resources to develop beyond a subsistence level.

The consequences of this lack of economic opportunity on tribal lands are dire. For instance, the Navajo Nation—which stretches across New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah—has a poverty rate of 38 percent (more than twice the poverty rate of those states) and an estimated unemployment rate of 50 percent—more than three times greater than the US unemployment rate at the height of the pandemic (14.8 percent).

What’s more, the lack of local businesses means that most money earned by Native workers on the reservation is spent off-reservation, hindering the accumulation of community wealth. A 2018 Navajo Nation report finds that less than 35 cents of every dollar a Navajo person earns is spent in Navajo Country, meaning nearly two dollars in three are not retained, but instead leak out to the broader non-Navajo economy.

In a study that Change Labs coauthored with Casual Design, the Navajo Nation ranked among the bottom 15 percent of countries for ease of starting and running a business. The study, which used the World Bank’s Doing Business framework, was the first comprehensive survey of a US tribal nation’s business environment. We identified the lack of access to land, infrastructure, and finance, as well as arduous bureaucratic processes, as critical obstacles to Navajo entrepreneurs’ success.

Accessing a plot of land on which to run a business on the Navajo Nation requires four times as many procedures and takes six times as long as obtaining a lease or property in a non-tribal territory. Why? Because of legacy federal policies like the Dawes Act that were designed to deprive tribal communities of their most valuable resource—their land. As a result, the Navajo Nation is home to a vast patchwork of land classes, all under the jurisdiction of different administrators with different rules, regulations, standards, and processes. There is no clear map, much less administrative process, to guide individuals and business owners in obtaining a site lease. In the Navajo Nation, about 95 percent of its 15.43 million acres of land is tribal trust land, a status that technically places land ownership in federal hands (in the supposed “benefit” of tribal nations) and keeps individuals from owning or acquiring plots of land (thereby making the use of land as collateral for loans nearly impossible).

Running a home business comes with other visibility and growth limitations, since an estimated 50,000 Navajo homes and buildings on tribal lands lack federally registered addresses. That means business owners can’t easily obtain an Employment Identification Number with the Internal Revenue Service—a process that normally takes mere minutes in non-tribal areas.

There are workarounds, but they come with their own costs. For instance, many promising Native entrepreneurs reluctantly launch their businesses in border towns, but this deprives their home communities of most of the benefits; for instance, property tax dollars in border towns accrue to the towns, not tribal nations. One entrepreneur who Change Labs supported, Laura Clelland, spent a year seeking a site lease for her business, Salt Woman Professional Foot Services. Salt Woman provides essential foot care to diabetes patients. Clelland wanted to establish her business on-reservation so community elders wouldn’t have to travel to border towns to obtain the treatments they need. But after an exhaustive search in her home Arizona community of Dilkon, Clelland was forced to register her business in Winslow, the closest border town.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Ahsaki Chasheri, a successful Navajo beauty entrepreneur and founder of Ah-Shi Beauty, secured a business site lease in Window Rock after running her storefront out of Gallup, New Mexico for a year. (She was forced to close four days after her grand opening, due to the pandemic.)

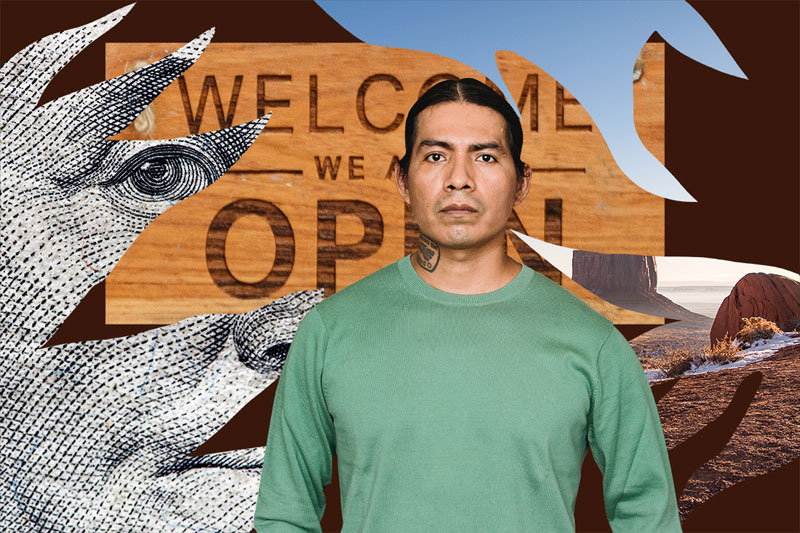

Navajo fashion designer Reno Tsosie wants to relocate his Dallas-based menswear company Hashké onto the reservation. The business promises to deliver local jobs, but Tsosie is struggling to secure the housing, land, and infrastructure needed to transition his business.

Change Labs itself has also been affected by these structural barriers. Technically, despite being a Navajo organization, it is registered in Arizona and is therefore, legally speaking, a “foreign entity” on Navajo Nation land. Now Change Labs is preparing to break ground on a new headquarters in the largest Navajo town, Tuba City. But that win comes only after four years of seeking a business site lease.

Infrastructure and Finance Gaps

A lack of physical and entrepreneurial infrastructure is another major barrier to Native entrepreneurship. Much of the Navajo Nation is neither grid-connected nor mobile or broadband-connected. Whereas rural communities elsewhere have benefitted from widespread mobile connectivity, data transfer and download speeds on Navajo land remain too slow to reliably perform e-commerce or mobile money transactions, much less host video conferences or download educational and business resources.

Navajo entrepreneur Cherilyn Yazzie wrestled for six years with the process of obtaining the site lease to her home to register her farming business, Coffee Pot Farms, whose mission is to provide a local and sustainable source of food for the community. While she eventually managed to obtain a land lease, Yazzie’s business activity is affected daily by the reservation’s lack of infrastructure. She presently is manually hauling water to her farm while navigating the process of drilling her own well. The weekly costs of investing in her own infrastructure and navigating bureaucracy dramatically affect business productivity and income.

There is also a considerable lack of business support infrastructure, like retail space and designated economic zones. The inability, due to federal trust restrictions, for individuals to obtain direct title to land is one major constraint. Capital is also scarce. The Navajo Nation has just one community development financial institution (CDFI) that offers a limited number of small business loans. Our nonprofit is the only business incubator on the 27,413-square-mile reservation (and one of the few Native-run business incubators in the US as a whole). While our headquarters will serve as a registration address for several Navajo startups, it is impractical for entrepreneurs to physically relocate to Tuba City to run their companies.

Helping Native Entrepreneurs Succeed

The regulatory and bureaucratic burdens that Navajo and other Native entrepreneurs face deeply impact the social and economic development of tribal nations. Native entrepreneurs who manage to run their own businesses must constantly compromise business ease with investing in their local communities, putting them at odds with their cultural values. Indeed, many businesses in our incubator indicate they feel like they’re “working against the tribe” to operate their businesses.

Incubator members are also constantly harmonizing their traditional values with mainstream business practices, particularly when it comes to securing working capital. With every decision, they must weigh how to generate the profit and growth needed to satisfy investors and lenders without offending tribal elders, sacrificing sacred ways, or destroying sacred lands.

“When it is easier to do business, more people can see themselves as entrepreneurs, more jobs are created, and as a result, economies thrive, and all the benefits of increased economic activity reverberate through the population,” Change Labs wrote with Casual Design in our Doing Business on the Navajo Nation report last year. Our recommendations include streamlining the process for acquiring land for small businesses, enabling local Navajo governments to define entrepreneurship zones in their community, and leveraging technology to ease business compliance and tax payments.

Many of these solutions require policy interventions. Others just require willing partners and patient capital. Here are three ideas for how to start, or expand, support for Native businesses and their communities.

Invest in finding and funding Native-led organizations that are providing entrepreneurial support services to their communities. It’s difficult for Native-led nonprofits to gain traction and visibility for the same reasons that it’s difficult for Native businesses to do so. In turn, these organizations often get overlooked by foundations and investors searching for ways to support Native communities. There are many organizations built by and for Native communities who are doing great work, however, including IndigeHub in Window Rock, Arizona, and Native Women Entrepreneurs of Arizona. These organizations, more than nationally focused or non-Native organizations, best understand the needs of their communities and their cultural, political, and economic contexts.

Promisingly, there will soon be more and easier-to-find Native-led business support organizations, thanks to the Native Business Incubator Act, a federal program passed in 2020, which US Interior Secretary (and former New Mexico representative) Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna) helped shepherd through Congress prior to her cabinet appointment. The new program will provide small grants to tribal entities and nonprofits supporting enterprise incubation and acceleration within reservation communities.

Design programs tailored to Native communities’ unique circumstances and needs. Change Labs has many supportive and committed backers, without whom its work would not be possible. But none of our partners actively focus on Native causes; rather, they fund us through generalist programs, like “scaling entrepreneurship,” “technical assistance for rural communities,” or “diversity and inclusion.”

As a result, Native-led nonprofits often find themselves in tense situations with partners who do not understand their unique challenges. For example, Change Labs has frequently been in the uncomfortable position of explaining why it could not accelerate plans for its new headquarters and why it has yet been unable to spend funding earmarked for construction. This could be avoided if more individuals in philanthropy recognized the unique challenges that Native organizations face or designed programs that are tuned into the realities of development in Native communities.

Seek Native input in how to redesign capital and resources to be culturally relevant. To set up Native-led organizations for success, partners and funders must understand what “success” means for Native businesses and communities. Success for the Navajo, for example, is not growth for growth’s sake; it is sustainable growth that nourishes our people and natural environment. Standard “success metrics” like scalability, revenue growth, or jobs created may not be the appropriate metrics. To address this, funders and Native partners should co-create evaluation frameworks.

Examples of this kind of thoughtful engagement with Native-led organizations can be found if you look for them. The Kauffman Foundation provided a flexible grant that gave Change Labs the freedom it needed to design appropriate metrics. Impact investor RSF Social Finance offered a loan to Native-led CDFI Akiptan that aligned with Akiptan’s lending terms to community borrowers. Investment advisor Candide Group helped Native American Natural Foods secure its first institutional investment, with terms that preserve the company’s Native ownership and community mission.

Many mission-driven funders and investors champion causes that align with Native goals of empowering people and communities, honoring natural resource constraints, and replenishing the environment. Supporting Native business ecosystems requires creative, thoughtful, and patient interventions, but it’s also a surefire way to achieve the social, economic, and environmental transformations that we all desire.