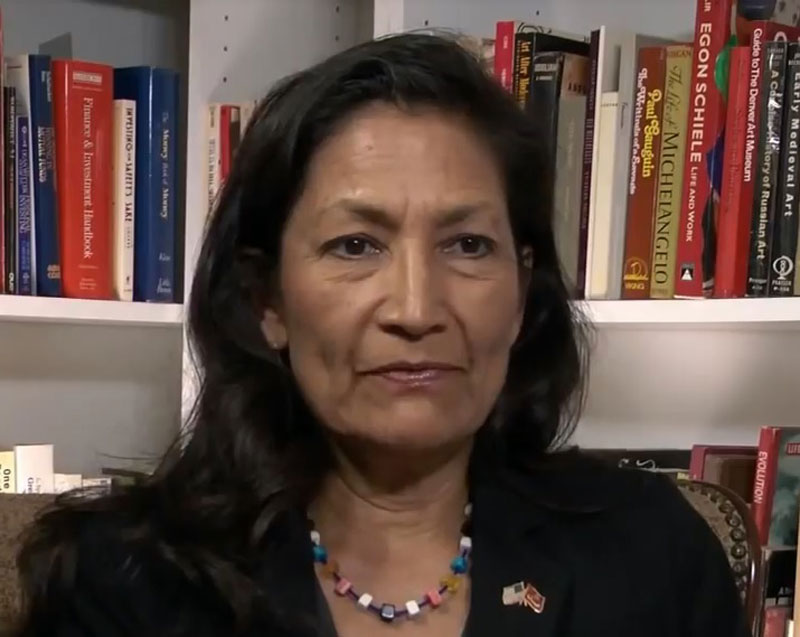

This past Tuesday, the US Senate’s Energy and Natural Resources Committee held hearings on the nomination of US Representative Debra Haaland (D-NM) to head the federal Department of the Interior. Haaland is a Pueblo of Laguna citizen and one of the first two Native American women ever to serve in Congress; if confirmed, she would become the first Native American cabinet member in US history. Her nomination has been a cause of celebration among many, including at NPQ, which, prior to her nomination, wrote that her selection at Interior would be a “compelling choice.”

That said, Haaland’s journey has not been smooth. GOP members in Congress have opposed her nomination, claiming Haaland is too hostile to fossil fuel industry interests.

In response, Native American groups in particular have mobilized. The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) sent a letter of support to the committee chair, Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), and ranking member Senator John Barrasso (R-WY). In it, they point out Haaland’s record of accomplishment in Congress, including playing “an instrumental role in the passage of Savanna’s Act and the Not Invisible Act of 2019.” She also got a third bill passed, the Native American Business Incubators Program Act, a $5 million annual grant program within the Interior Department for tribal businesses, educational institutions, or other organizations.

The publication GovTrack Insider notes that getting three bills passed in Congress is “a pretty good number for any member of Congress during these polarized times, but especially for a first-term representative who doesn’t serve in an official leadership role.” GovTrack Insider also reports that Haaland found Senate cosponsors for 15 bills she authored last term—“more than any other House member, freshman or otherwise.”

In her opening statement to the Senate committee, Haaland was open and direct about her humble roots and what her Indigenous background taught her about respect for the land and the peoples who inhabit it. As Haaland concluded, she said:

If confirmed, I will work my heart out for everyone—the families of fossil fuel workers who helped build our country, ranchers and farmers who care deeply for their lands, communities with legacies of toxic pollution, people of color whose stories deserve to be heard, and those who want jobs of the future.

I vow to lead the Interior Department ethically and with honor and integrity. I will listen to and work with members of Congress on both sides of the aisle. I will support Interior’s public servants and be a careful steward of taxpayer dollars. I will ensure that the Interior Department’s decisions are based on science. I will honor the sovereignty of tribal nations and recognize their part in America’s story, and I’ll be a fierce advocate for our public lands.

I believe we all have a stake in the future of our country, and I believe that every one of us, Republicans, Democrats, and independents, shares a common bond, our love for the outdoors and a desire and obligation to keep our nation livable for future generations. I carry my life experiences with me everywhere I go. It’s those experiences that give me hope for the future.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

If an Indigenous woman from humble beginnings can be confirmed as Secretary of the Interior, our country holds promise for everyone.

This statement came as no surprise to Debbie Nez-Manuel of the Navajo Nation. After watching the hearing, Nez-Manuel felt Haaland demonstrated she was willing to learn from others. “She is about protecting what’s there, what’s good for humanity, not for pocketbooks,” she said. “That’s something that stood out very clearly.”

NCAI President Fawn Sharp of the Quinault hopes to educate both lawmakers and the general public about Haaland’s strong record. She is joined in this effort by many across the country. In Montana, the Rocky Mountain Tribal Leaders Council erected two billboards with Haaland’s picture in Billings and Great Falls, where Senator Steve Daines (R-MT) is one of her harshest critics. Native people are 6.8 percent of Montana’s population. Sharp is also encouraging people to call and write letters of support to their home state senators in support of Haaland.

“We are not invisible,” says Holly Cook Macarro, chair of the American Indian Graduate Center. And Julian Brave NoiseCat, who helped develop the Green New Deal, says of Haaland, “She’s a progressive, sure, that’s undeniable. But all of her colleagues love working with her, including Republicans, who sing her praises. It makes me wonder as a Native person if they would be treating someone with a different background differently, and I think Native people have the same question.”

“This is no different than when Obama became the first Black president and what that signified,” observes Brandi Liberty, who lives in New Orleans and is a member of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska. “This is a historical mark for Indian Country as a whole.” Her thoughts were echoed by 21-year-old Zachariah Rides At The Door, a member of the Blackfeet Nation of Montana who’s a third-year student at the University of Montana in Missoula. Haaland, he believes, is opening doors for other Native Americans, especially youth. He says, “It’s a great way for younger Natives to say, ‘All right, our foot is in the door. There’s a chance we could get higher positions.’”

Haaland’s ride to confirmation still faces challenges. Yesterday, for instance, The Hill reported that Daines pledged to “block and defeat” Haaland’s nomination. However, on the same day, Manchin publicly indicated his support for Haaland. With Manchin’s important support, confirmation is quite likely. Absent Democratic Party defections, Daines and his GOP colleagues can slow, but not stop the nomination.

But why has Haaland’s nomination sparked such GOP opposition? Perhaps Representative Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ) put it best when he suggested that Haaland’s opponents fear she will be her own person as she works on addressing the climate emergency. “The protection, the conservation of our public lands and waters, and the role they can play in remediating and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions is huge, and that’s a role that has not been played,” Grijalva observes. Grijalva also emphasizes the historic nature of an appointment of a Native American to run the department that deals with federally recognized tribal nations. “What we’re doing is turning history upside down on its ear,” Grijalva says. It’s about time.—Carole Levine