March 11, 2019; Pittsburgh City Paper

Nonprofit grantees recognize that no social ill operates in isolation—and they are holding their grantors to account.

NPQ has written about bad donors who attempted to charity-wash their activities, and how nonprofits have begun to eject board members and/or reject donors whose values are incongruous with the organization. Immigration advocates in Pittsburgh are organizing this month to challenge the Colcom Foundation. Advocates accuse Colcom of “greenwashing” their funding for anti-immigration research and advocacy.

The Colcom Foundation’s tagline is “Committed to a sustainable future,” and they identify themselves as conservationists. They fund a lot of environmental nonprofits, such as the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Environmental Integrity Project, the Clean Air Council, and more.

But Colcom argues that overpopulation is a major threat to environmental protection, and as such seeks to restrict immigration to the US. (How keeping people in one country versus another ameliorates a problem like climate change, which does not recognize national borders, is unclear.)

Primarily, the foundation seeks to protect natural resources by funding anti-immigration advocacy groups like the Center for Immigration Research (CIR) or the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR). Both organizations have been recognized by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) as hate groups and have ties to the current White House administration and its dehumanizing immigration policies. Colcom has donated $150 million to CIR, FAIR, and their peers since 2005.

Colcom argues that their funding of environmental and immigration groups represents two approaches to a single goal, that of natural preservation. Evidence shows, however, that isolationism is a major priority, and community advocates have called their environmental funding “greenwashing.”

Colcom Foundation was founded by Mellon family heiress Cordelia Scaife May in 1996. The Mellon family fortune stems partially from natural resources like steel, aluminum, coal—and oil. In 1907, Andrew Mellon bought an ownership stake in what’s now the gas giant Chevron. So it seems right that May’s money should go to repairing the damage wrought by natural extraction, and some of the groups Colcom funds, like Earthworks and Citizens Coal Council, do actually challenge the fossil fuel industry—though Heidi Beirich of the SPLC notes that nobody with Colcom funds is working to support the Environmental Protection Agency.

The “overpopulation” concern, though, is a thin veneer for racist isolationism. For one thing, though May reportedly advocated for birth control access in her early days, Colcom’s concern about population control seems to apply exclusively to non-US citizens. Many papers have been published about birth and population control as weapons of colonialism, and indeed some of May’s comments (which we will not print) echo gross stereotypes about women in the Global South.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For another, both May and her close advisor John Tanton, a cofounder of FAIR, frequently expressed concerns about “the evils of multiculturalism.” Some of them were absurd (English is in no danger of obsolescence) but none of them have any relation to environmental issues.

It’s true that the earth’s population ballooned in the 20th century; after staying under two billion until 1928, in less than a hundred years, the population has nearly quadrupled to 7.7 billion. The BBC, the Guardian, and Yes! magazine, among others, have all asserted that humans have overpopulated the planet. But even if that were true, it has nothing to do with immigration.

Immigration lawyer Hassan Ahmad said, “It is safe to say that without [May’s] money, the anti-immigration movement…would not exist. These organizations are deeply embedding their networks into the Trump admin and existing policy. None of that would have happened without the funding.”

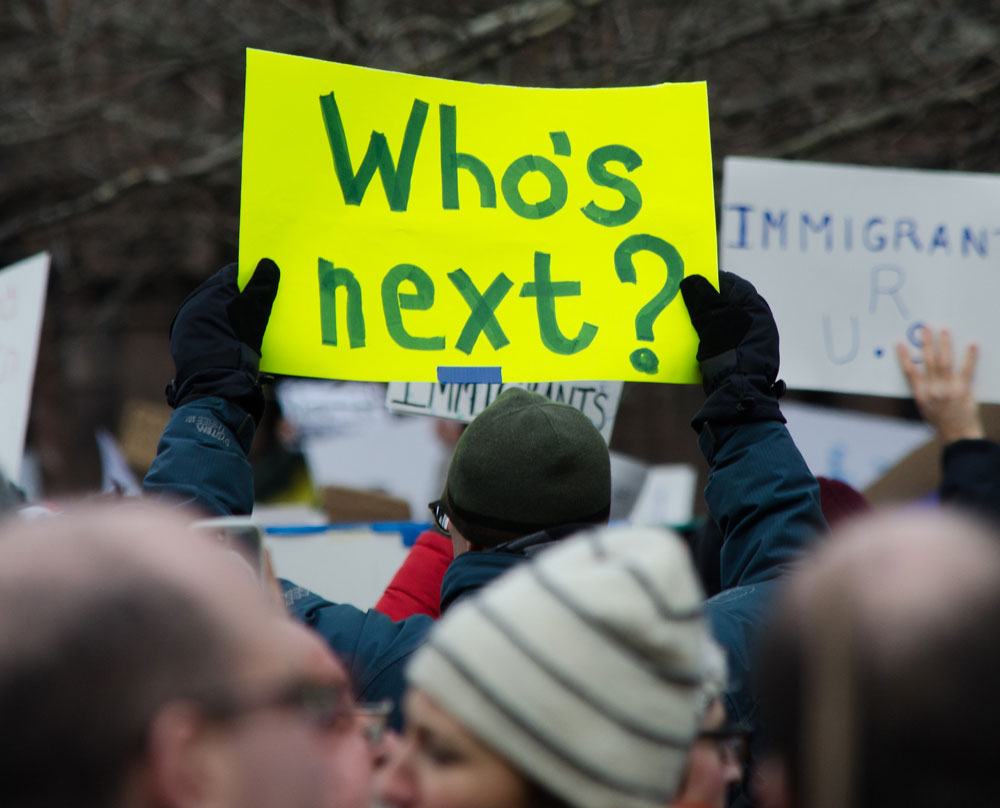

Pittsburgh community members have risen up to demand an end to the conflict of values. They’re targeting not just Colcom, but the groups that take their money and enable the greenwashing of anti-immigration activity.

Advocates sent letters to local groups funded by Colcom, asking them to reject the money and denounce the foundation. Guillermo Perez, head of the Pittsburgh chapter of the Labor Council for Latin American Advancement, said, “If they don’t want to wake up to what Colcom is, then we will call them out.”

Ahmad said, “As an immigration lawyer, I have spent the majority of my time putting out fires. If we don’t spend time asking where the fires are coming from, if we don’t spend time putting those out, we are just going to be having the same conversations in perpetuity.”

One important conversation that keeps getting overlooked is that immigration and climate concerns are closely tied—just not in the way Colcom thinks. Climate change is already making some areas uninhabitable, whether due to disasters or simple lack of water and arable land. UNHCR recognizes “environmental degradation and natural disasters” as major drivers of refugee movements and estimates that in 2017 alone, 18.8 million people were displaced by natural disasters.

Cyndi Suarez wrote on Tuesday about designing for “sustainment,” and how the only appropriate response to climate change is a redesign of our collective systems and ways of being—a redesign that takes into account both environmental and racial equity concerns. Preservationist, isolationist thinking advocated by Colcom-funded groups like FAIR actively works against a sustainable future because it fails to recognize the scale of change needed—or the collective human effort that will be necessary to achieve it.

Nonprofits already know well that real change in any human concern can’t be isolated from related areas—climate work can’t be done without attention to racial, economic, health, and wage justice. Pittsburgh is rising up to spread and enforce that principle and advocate for an accountable community.—Erin Rubin