March 22, 2013; Source: Washington Post

While we in this sector are used to all manner of internal conflicts on our boards, it is seldom that we see an outside party attempt an aggressive coup to take over a board’s leadership. The Washington Post’s recent article about the storied Corcoran discusses such an attempted coup and is also a twist on that ugly moment that some institutions face when a donor starts trying to take more of a directive role than anyone agreed to – except in this case, Wayne Reynolds is not a donor but a moneyed and connected activist with a great deal of self-confidence. He may have some grounds for self-confidence; as chair of the board of Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., Wayne Reynolds led the charge to raise $54 million, far outstripping anyone’s expectations.

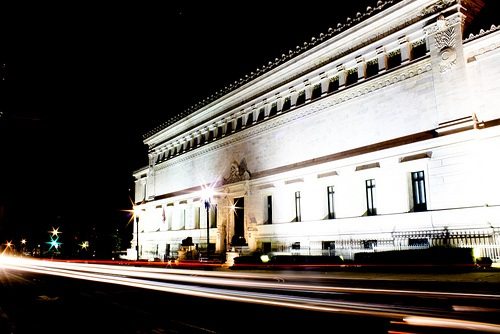

Now he’d like to repeat the performance for the famed Corcoran Gallery of Art. According to the Post, the Corcoran ran a $7 million deficit in 2011 and were it not for the sale of a parking lot for $18 million, it would have done approximately the same last year. But Reynolds’s showy and ambitious largesse comes with an agenda that some say is not only audacious but has the potential to destroy the Corcoran, the oldest private art museum in D.C.

Reynolds begs to disagree and his effort, which begins with a fancy reception complete with open bar on Friday, is baldly named “Save the Corcoran.” The Post reports that he has been unflinchingly open in his bid not only to get a seat on the board of trustees but to occupy the position of chairman. For this to happen he would, of course, have to unseat the current occupant, the art collecting venture capital mogul Harry F. Hopper III.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The art world is abuzz with this uncharacteristically public spectacle. Harry Philbrick, museum director at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, observes, “It’s an unusual situation, absolutely, in that it seems to be more like a corporate boardroom maneuver, where someone is trying to come in and take over… Certainly there are [attempted] changes of leadership in the art world, but they happen in a low-key, behind-the-scenes sort of way.”

But Reynolds is evidently not a low-key kind of guy. He is the president of the American Academy of Achievement, a nonprofit founded by his father, celebrity photographer Brian Blaine Reynolds (formerly Hy Peskin). At the Academy, which is designed to bring young achievers together with statesmen and Nobel Prize winners, he reportedly pays himself a humble $695,000. His wife is philanthropist Catherine Reynolds, who made her fortune on a student loan business she sold in 2000. Subsequently, she has reportedly made contributions of somewhere in the neighborhood of $100 million to the arts and education. One of the beneficiaries has reportedly been her husband’s nonprofit. Just a note about why the Corcoran board may have good reason to be wary of Reynold’s as visionary savior: Ms. Reynolds is known for having taken back a $38 million gift to the Smithsonian in 2002 when the institution opposed her vision for one of the museum’s halls.

“The Corcoran is outraged at Mr. Reynolds’s reckless publicity campaign waged against the very institution he seeks to appoint himself to lead,” Mimi Carter, Corcoran vice president of marketing and communications, comments in a written statement. “The Corcoran’s Board of Trustees and staff remain focused on finishing the diligent work that is currently underway — without outside distractions — to lead the institution to a sustainable model for its future.”

Reynolds says he has no choice but to stage a revolution because Hopper has no intention of allowing him to meet with the board to promote his vision for what he calls a national Corcoran Center for Creativity. Said vision would refocus the museum on digital art, photography and contemporary art and it would sell off rarely displayed pieces in the current collection to raise funds for the endowment. Philip Brookman, the Corcoran’s chief curator, believes that such a move would be “stupid,” adding, “You would gut the collection. . . .The Corcoran would become ostracized from the community of museums.”

Still, Gary Vikan, executive director of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, thinks that there is some benefit to the public spectacle in that the public will end up being very informed about the Corcoran’s choices. Unfortunately, the board seems to have blown by their own deadline for coming up with a plan to stop the leakage. A plan was to have been decided upon by mid-March, but the next meeting of the board is April 3. This situation bears watching as it unfolds. –Ruth McCambridge