Disruption liberates us from the status quo. It sparks innovation. Pick your system: education, healthcare, politics, you name it. Disruption is everywhere. Coronavirus puts disruption on steroids. Journalism, a system of cultural nonfiction storytelling, helps make sense of upheaval. Yet it, too, is in the midst of a revolution.

Students of ecosystems know that when a species dies, it opens the space for a different animal to move into the niche.1 When a keystone species, like elephants or newspapers, dies, it opens the way for total collapse or for something novel to emerge.

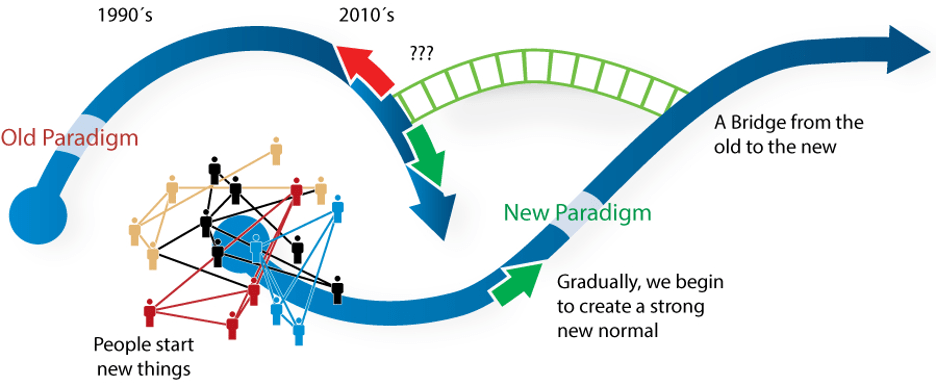

The Two Loops2 theory of change in the picture below offers a view into how disruption transforms systems. A paradigm is a set of ideas that shape structures. Our current paradigm has peaked and is declining. Meanwhile, innovators experiment. New ideas emerge that shape novel, often more inclusive structures. Ultimately, bridges provide paths for people to cross the chasms.

This pattern describes what is happening in journalism. It offers a story of hope and possibility, even as local and regional newspapers implode—an implosion from lost ad revenues, hastened by the novel coronavirus. Intrepid adventurers, mostly working locally or regionally, are reinventing journalism that serves the needs of an inclusive society.

The table below highlights shifts underway in local and regional journalism. It reflects the changing assumptions from an old to a new paradigm. Many see the First Amendment as a de facto charter for journalism’s role in civil society. It provides a framework for understanding the new paradigm. An expansive interpretation of First Amendment freedoms—religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition—suggests a different way of conceiving the journalistic enterprise. The implication: Journalism is moving towards an expanded role. It is fostering participation in civic life.

Table 1. Framework for Civic Journalism

| 1st Amendment Freedoms | Traditional | Possible Future | Trend in Journalism | Action/Outcome |

| Religion: Freedom to express who we are holds responsibility to encourage a spirit of belonging | Monocultural | Multicultural | Community first | Include/Belonging |

| Speech: Freedom to speak brings the responsibility to connect and listen deeply | Lecturing | Listening | Relational | Connect/Compassion & Trust |

| Press: Freedom to tell our stories brings the responsibility to be constructive, to inspire by illuminating possibilities | Problems | Possibilities | Constructive | Inspire/Holistic cultural narrative |

| Assembly: The right to assemble can be used to engage in dialogue across difference, activating the public | Debate | Dialogue | Engaged | Activate/Innovation |

| Petition: When things aren’t working, it is the right—and responsibility—of the people to adapt the system to their needs for a more perfect union. To strive for E pluribus unum—out of many, one. | Go alone | Come Together | Collaborative | Adapt/Individual freedom & common good |

Elements of these shifts in journalism are already in motion, introduced by such intermediaries as Hearken, Solutions Journalism Network, SpaceShip Media, and Journalism That Matters. The emergent paradigm resulting from these efforts is changing how journalists listen, tell stories, engage, and support their communities in imagining a better future. Of course, there remains the matter of money. No one has cracked the code on a viable business model for local journalism. But in the interim, philanthropy, which has already moved in this direction, can provide a vital bridge to support the emergence of the journalism we need today.

Of course, even as a new paradigm emerges, it is clearly not dominant yet. Indeed, at present, we are experiencing fragmentation, conflict, and the noise of too much information and misinformation. Yet the global pandemic has made clear that we’re all in this together. Journalism’s transformation is neither straightforward nor guaranteed. But it is possible. We can accelerate the creative, courageous work of people who are liberating journalism. It can spark a renaissance which liberates people to engage in civic life.

In revolutionary times, the opportunity for new ideas to take root is high. What better way to invest our energies than to accelerate the reinvention of journalism of, by, and for the people?

Community First: From Monocultural to Multicultural

What if journalism supported a widespread sense of belonging, not because we conform, but because we bring our uniqueness of being?

The American Society of News Editors has tracked newsroom diversity since 1978. In that year, the workforce in daily print news was 96-percent white. Today, diversity remains a challenge: 78 percent of the daily print and online-only news workforce is white, while 37 percent of the US population are people of color. It’s not surprising that most news organizations miss stories that accurately reflect and matter to communities of color. Not to mention helping white people understand what those stories mean to them.

KPCC, a public radio station based in southern California, is discovering how to be a multicultural news organization. Ashley Alvarado, KPCC’s Director of Engagement, led them to create an award-winning engagement portfolio with activities like “Feeding the Conversation” and the “Human Vote Guide.”

Alvarado draws a useful distinction between audiences and communities. Audiences are the people who already interact with a news organization. Communities are the larger bodies that make up the geographic or interest area served. Most communities are more diverse than the audience reached. To change that, Alvarado, with managing producer of live events Jon Cohn, conceived Unheard LA, a live storytelling show. Real people share stories of struggles, survival, hope and fears, of the unexpected and the unbelievable.

Unheard LA is turning community members into audience. Journalists are developing a more nuanced understanding of their communities. Community members are celebrated for who they are and affirmed in belonging to their community.

Journalism as Relational: From Lecturing to Listening

How do journalists and the larger culture hear our diversity of voices in ways that generate understanding, compassion, and trust?

Before the First Amendment, free speech could be punished at the whim of the British overlords. Today, hate speech and vitriol in public discourse are rampant. Journalism that increases listening fosters connection, compassion, and trust. They shift relationships among journalists and audience. By lecturing less and listening more, community can take a more central place in the journalism. Selecting stories, diversifying sources, offering new forms of storytelling and distribution that connect us.

Traditionally, information was scarce and hard to find. News organizations were a center for information, so they lectured. They told us what is going on and how experts interpreted events. Today, the internet makes information more readily accessible. We get news from friends through social media. No longer does a single authoritative voice speak for all of us.

In a cacophony of voices, journalism can be an effective community connector and curator. By listening and fostering listening among the public, deeper relationships bolster understanding, connection, and trust, journalism can move beyond amplifying the views of top-down gatekeepers or highlighting battles between sides. It can support understanding arising from community conversations. By lifting up many voices, including those of ordinary people, we all become grounded in a more holistic understanding of what’s happening.

Founded in 2015, City Bureau is a nonprofit civic journalism lab based on the South Side of Chicago. It brings journalists and communities together to produce media that is impactful, equitable and responsive to the public. They are breaking traditional definitions of who is a journalist with their award-winning Documenters project. Documenters are intergenerational and diverse, reflecting their communities. City Bureau recruits, trains and pays this group of engaged citizens to be the ears of their communities. They monitor local government and contribute to a communal pool of knowledge. The award-winning model is being shared in other locations. They are democratizing local news and information, particularly in communities of color.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Two other organizations revolutionizing how journalists relate to their audiences are Hearken and GroundSource. These platforms support newsrooms in listening. If your local news organization has posed a question and invited a public response, chances are they are using Hearken. If they connect with you by text message, there’s a good chance Groundsource is behind it.

Journalism as Constructive: From Problems to Possibilities

How can journalism inspire us to step in, not opt out?

When news organizations tell stories without meaningful context, some, often people of color, are misrepresented or rendered invisible. By reporting mostly problems, people check out. Constructive journalism doesn’t shy away from problems; instead, it puts them in perspective. It tells stories within a situational context. It paints a nuanced picture of what happened and what’s possible. “News fasts”—avoiding the news for mental health—become irrelevant.

The Evergrey, an online news organization in Seattle, develops stories about complex topics starting with listening to its audience. They foster civic engagement. They take on tough subjects, like homelessness. They also offer fun to the thousands of millennials moving to the city. Their events help people meet others and get involved in civic life. Their brilliant mix of highlighting people and places, providing context about the city to the many newcomers, and offering ways to get involved integrates them into the community. They’re also willing to experiment. Following the 2016 presidential election, they invited readers on bus trip to rural Oregon for an in-person conversation across political divides.

Two leaders in bringing constructive journalism to newsrooms are the Solutions Journalism Network in the US and the Constructive Journalism Network in Europe. Find out who is trying something constructive in your geography from their websites. Encourage your local newsroom to learn about their work.

Journalism as Engagement: From Debate to Dialogue

How can journalism foster understanding across differences?

Democracy requires us to talk with each other.3 Reading words on a page or a screen are individual acts. We create through our interactions. In dialogue, differences spark curiosity and connection. It can activate people to create together. Through “engagement editors,” some journalism organizations are inviting the public into dialogue.

Convening community dialogue—as many media, like Capital Public Radio in Sacramento, have done—goes beyond journalism’s traditional role of providing information people need. Some engagement editors are hosting community conversations. These conversations connect people with others who care about an issue. It can activate the public to get involved in complex issues like homelessness or the opioid crisis.

Spaceship Media, working with the Alabama Media Group, provided an online space for dialogue shortly after the 2016 election. They brought together women from Alabama who voted for Trump and women from California who voted for Clinton in a Facebook group for two months. The journalists listening contributed stories in response to questions raised by the group. For example, in discussing the Affordable Care Act, the women wondered why progressive women loved it and conservative women hated it. Journalists reported on how different the implementations were. In Alabama, costs went up and options went down. It was just the opposite in California. At the end of the project, the women chose to keep meeting. Their meetings didn’t change minds; that wasn’t the point. They did change attitudes and fostered new relationships.

Spaceship Media continues to be a platform for bridging divides, supporting news organizations in hosting conversations on guns, agriculture, education, immigration, and more.

Journalism as Collaborative: From Going Alone to Coming Together

How does journalism play its role in a system of civic engagement for our common good?

Journalists often pride themselves on being independent, objective observers. But increasingly, stories like the Panama papers have succeeded through collaborative efforts. Many news organizations are partnering with other types of organizations to host meaningful conversations, community storytelling, and even arts events. These innovations connect them in an interdependent web of civic engagement that supports communities and civic life to thrive. They help develop the capacity for discovering common good. They can help us dream together about the futures we want and generate widely embraced responses to collective challenges and opportunities.

News organizations are partnering with libraries, civic organizations, and others to take on issues like homelessness. Journalism That Matters worked with Impact Hub, a social innovation incubator, The Evergrey, and Seattle’s street paper Real Change to host Mobilizing creativity, compassion, and community to address homelessness. Arts/media organization collaborations also cultivate a more cohesive community. For example, The Center for Investigative Reporting has used theatre to deal with deadly serious subjects like rape in the fields in US agriculture. WETS in Jonesborough, Tennessee hosts a radio program, Story Town Radio Show (formerly Yarn Exchange) using a storytelling practice called StoryBridge to create a monthly radio play. The community provides real-life stories and forms the cast. The plays strengthen community, compassion, and trust.

We are in the early days of discovering the power of such collaborations to reweave the fabric of our communities. They seem to renew our structures of civic life so that a diverse populace feels their uniqueness matters and they belong. Early signs are the collaborations grow commitment to a shared sense of the common good.

Together, these shifts underway could bring about a more inclusive, just, compassionate, and engaged society.

Notes

- “Keystone Species in an Ecosystem.” National Geographic. (National Geographic, 2020).

- Two Loops.

- Munson, Eve Stryker, Catherine A. Warren, eds. James Carey: A Critical Reader, University of Minnesota Press, 1997. (Munson & Warren, 1997)

Peggy Holman is based in the Seattle area, a cofounder of Journalism That Matters, a nonprofit that connects journalism and communities. She is the author of The Change Handbook and Engaging Emergence: Turning Upheaval into Opportunity.

Correction: This article has been altered to acknowledge the role of Jon Cohn in the conception of Unheard L.A.