Authors’ Note: We came together through our genealogical research. Mary T. Hunley Hudgins Edwards (1806–1877) was Allison’s thrice-great-grandmother. Her plantation was on Gwynn’s Island. Her diary has two pages listing the nearly 40 enslaved people seized by the Union on June 5, 1863. On that list are Maria’s ancestors, including her great-great-grandparents “young Dolly” and Billy, 15 at the time. This article is adopted from a talk we gave to the Middle Peninsula African-American Genealogical and Historical Society (MPAAGHS) of Virginia on March 13, 2021. Where the pronoun “I” is used below, it refers to Maria.—MM and AT

It was part of the oral history of my family that we came from a long line of oystermen and watermen at Gwynn’s Island, Virginia. This was their home, where they decided to make a place for themselves after the Civil War. They had their own businesses. I knew my great-grandmother Ida had been a teacher. I knew my family had some education. And I just wanted to dig more deeply into all of that. That is where I started to find these records about post-war Gwynn Island and how they came to build a community.

Captain William Smith

I found proof from the National Archives of Billy’s service—Captain William Smith—in the Civil War with the Union army. After enslaved people were seized by the Union, considered “contraband” of war, many enslaved men enlisted to fight for the Union in the Civil War. We still don’t know where the name Smith came from. Perhaps the military required that you have a surname. In any case, Smith was it.

After the war was over, Captain Smith went back to what he considered home. And he began to establish his family by purchasing land and the things he would need to establish a business. For his family, it was being watermen. They were crabbers. They were oystermen. This is how they made their living, and they began to build their lives, to build the economy of the island.

Smith’s first purchase of land was for five acres for $75, probably using his mustering-out money from the Union cavalry. Five acres does not seem like a lot, but at that time, and given you’re on an island, it was a lot. It is the kind of land you live on—you can have siblings live on it, and your children begin to live on it.

The 1880 agriculture census data show that they grew potatoes and corn on the land and sold 60 dozen eggs that year. Now, 60 dozen eggs is not a lot to us, but it is a substantial part of their economy. They are also paying wages to other people to work for them.

They were also watermen. They were harvesting oysters, fish, and crab. That is the life they were leading. Smith has his own boats. He is not just working for someone else or being employed; he is building his own company, and later he worked in partnership with a guy who later becomes his son-in-law. A 1902 voter registration card shows he was a voter, despite the poll taxes. He had fought in the Union army and prioritized voting.

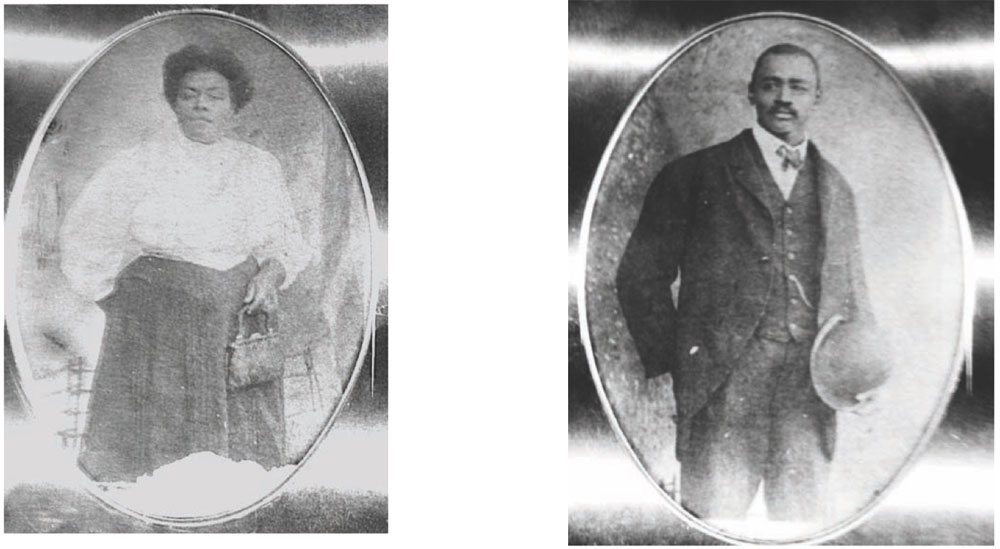

The next generation were James Henry Smith & Ida Baker Smith. My mother remembers Ida. She would tell me stories about her. She was a schoolteacher. She was very smart and very stern. James, I don’t have as much information about him. You can see from photos (above) that these aren’t people who were shabbily dressed. James has on a pocket watch. He has a bowler hat. They are not just getting by. They have become middle-class or upper-middle-class Black citizens. In the 1900 census, all four of their children are enrolled in school. The land is owned free and clear.

One of my most prized genealogical finds is the marriage certificate of my great-grandparents—William and Dolly’s oldest son, James Henry Smith, and his wife Ida E. Baker. This was something that they signed. It proves they were literate. A lot of them did read and write. And then I found other marriage bonds and marriage licenses of their children, their grandchildren, and things like that.

By 1910, James and Ida have some of their kids married off, and they have children also living nearby. William and Dolly are great-grandparents. They were really thriving. They were earning. They were providing for their families.

Jim Crow Intensifies on Gwynn’s Island

But times started to change, and you see more things coming in Jim Crow style. In 1912, a Confederate memorial was erected. In 1915, the high school was renamed “Lee-Jackson” after the two Confederate generals. Many white people wanted to believe that what they didn’t have as white citizens was because of what Black citizens did have.

I knew my family left Gwynn’s Island during that decade, but I didn’t know how or why. The story I was told by one of my aunts was “there was a situation,” so I immediately thought of Emmett Till and other stories in the South. Did someone say something about a woman? Was it a domestic situation?

And then I went to the Mathews County library and started asking questions. Initially, the librarian said, “I don’t think we have anything.” But I found an abstract from the newspaper that detailed a different version of the fight and the trial. I was surprised it was such a big deal. It started out on Christmas Eve of 1915 and went into the next year.

Here I am, just bouncing around the island, asking every person I can find, regardless of age and race, “Do you know anything about the Smith family? James Smith was my great-grandfather.” And I’m not thinking anyone would have a connection to this. That was a little naïve.

You look at the accounts. People today cover this up or don’t want to quite accept what happened. I think probably because it is such a shameful episode.

So, the story evolves over time. Some say Black residents left for better jobs. But there was an enormous prosperity at Gwynn’s Island at this time, with new packing plants opening, lots of new houses being built, and a new school being put up. Other people say the Black residents left by choice, one by one, but we found they left as a group or all at once. We found deeds and phone directories that document this.

A book by a white amateur historian named John Dixon tells the story likes this: On Christmas Eve, James Smith—or as they call him, “Jim”—is at a bar and a fight breaks out, and he breaks a bottle. He gets into a tussle with people, cuts somebody, and then he runs down the street and is saved by a storekeeper named Herbert F. Grimstead, who basically says, “You are not going to lynch him tonight; we’re going to wait, and the sheriff can arrest him.”

Dixon, reflecting the stories he was told by old-timers, describes Smith as a troublemaker, a drunk, and that he just out of nowhere started a fight, even though they were living amicably at the time. To think that a Black man is going to start a fight in a bar full of white people in 1915 is ridiculous, but that’s the way the story is told.

The newspaper mentions how cold it was. It was extremely cold, but even with that, the courtroom was packed. There was just an overwhelming number of people there. It covers this in a way it does not cover other trials. There is a lot of space in the paper about Jim Smith having maliciously wounded this person and then being convicted of it. But the names of Smith’s accusers are left out of the story.

I went back to the courthouse and was able to find the actual Special Grand Jury summary, and the pleading and all of that is in there. He has an attorney. He does not plead guilty, which would have been the easy way out. He could have said he was guilty, was drunk, and had messed up. Instead, he insists on a trial.

It was an all-white, all-male jury. It was people from mainland Mathews County, who might not have known Smith or his family. And he gets this light sentence (30 days) and a fine ($45). The fine was substantial, but it was payable. His father raises that money within six weeks of the trial.

You can see detailed handwritten documents. But there is no testimony. There are no depositions. They don’t name the complainants. You get a list of witnesses because each witness is paid $1, but the records don’t indicate who was for the defense and who were Commonwealth witnesses.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

We kept digging. We found records hidden in plain sight in the dead papers file in another part of the clerk’s office. It is kind of battered and everything was folded in thirds. Included is a scrawled piece of paper, with the judge’s personal notes of what he would tell the jury.

What’s interesting is the judge’s notes reveal a very different story about the case. The judge’s notes say there were two white men fighting with a Black man who was Smith’s brother-in law. Smith intervened to interrupt the “fuss” and was then himself assaulted by several white men. It became quite a fight. We do find the names of the complainants. They were both young fishermen, single. The witnesses are ages 15–20. There are three witnesses who are middle-aged married watermen. We also find who were the witnesses for James Smith. One white man who was in the original fight courageously testifies on Smith’s behalf. Also testifying for Smith were two Black men and his wife.

Smith’s standing in the community is evident in the way the trial was conducted. Smith has a lawyer. He calls witnesses. His wife testifies. And Grimstead, the shopkeeper who saved Smith’s life that night, likely testified that Smith’s life was in danger. In his instructions to the jury, the judge says that if the jury believes Smith used no more force than necessary, then they must find him not guilty. He’s effectively leaning on the jury to call him “not guilty” because he believes Smith acted in self-defense. The jury ignores this and finds Smith guilty.

Black Exodus

Shortly after the trial, even though Smith served his time and paid his fine, he is informed that people are going to lynch him. He is hidden away in a church for three days. He is told he needs to get off the Island now. Smith’s entire family is forced to leave a life where they have property and belongings and community and end up living in a less permanent situation.

It is obvious that the move was under duress. After all, if the Smiths weren’t forced out, why would they leave? If you got your sentence and served it and paid your fine, why wouldn’t you go back to work? The people on the island weren’t the only people Smith was doing business with. He was doing business with people on the mainland as a fisherman and oysterman and crabber. Why are you going to give that up? When I dug for information, that’s when I found the deeper story. They were just told, “You need to get out of here.”

Life in Norfolk

The Smiths become renters in Norfolk. They settle in Norfolk because Ida’s family has connections there. The sons begin working as delivery drivers. Some become chauffeurs later and take on other jobs, becoming mechanics. Ida no longer teaches; she becomes a housewife. It really displaces everyone.

Remember, the Smiths weren’t the only family that left in that overnight exodus. Imagine this multiplied by 20–30 times, with families having to leave everything they have and ending up in different cities. It changes everything. Smith goes from someone who owns his own business, pays wages, and owns property to renting where he lives and working a hard menial job shoveling coal. His older children move to Hampton and build their lives there.

The family is never the same. If you look at the census records, in 1930, Smith is paying $22.50 a month in rent. He is still a coal trimmer. Both of his sons die of tuberculosis in their forties. Smith now has the Jackson children living with him because his daughter and her husband moved to Hampton, lost a baby to pneumonia, then she died of childbirth. That baby died a year later, and then her husband dies of cancer. There is just this cascading trauma.

Is it a lack of medical care? Perhaps. We do know that Smith and his wife died before the decade was out. James died of a heart attack at 66. And Ida dies of diabetes a few years later. But the people who purchased the land on Gwynn’s Island, they lived very long lives, almost to the age of 100. It is very disproportionate. Black men and women who had this prosperous life in the community, they die young, as do their children and grandchildren.

Research Continues

We keep digging to learn more. A descendant posted a blog in Mathews County in 2009 that said his great-grandfather, who had attended the trial, overheard one of the white men who filed charges against Smith saying he had lied. These guys were 20 and 23. They had to come home for Christmas all cut up. Perhaps they felt the need to come up with an excuse.

And there were more threats of violence. While Smith was in jail, people were talking about lynching him. By the time Smith got out of jail, things were very dire. Maybe people were unhappy he got a light sentence. One woman rather proudly says, “My granddaddy was in the lynching party.”

The first acreage William Smith sells is three acres to one of the older white defense witnesses for $500. Maybe land was behind this. Probably this man was pushing to get Smith’s land. The second piece of acreage is sold to the brother of the storeowner where the initial fight took place. The sales happened extremely quickly. They were getting pretty good money, but these were not voluntary sales. The Smiths had wanted to pass this land to their children and grandchildren.

By the end of 1920, all the Black families had moved elsewhere; by the end of 1922, almost all their land had been sold. And on October 5, 1924, the Sunday edition of the Richmond Times-Dispatch profiles Gwynn’s Island with a full eight-column feature. The article’s title was “White Man’s Paradise Nestles in Virginia Bay.”

Reflections

When I explained our findings to my family, one descendant, now in his forties, said, “I can only imagine the shape my life would have taken if I had known this history years ago. I thought that all I inherited from my ancestors was anger. Now I know they tried their best.”

The narrative is so faulty. It’s just a lie. But you look at how people feel today. These are not easy lives. When you think you’re having a bad day, consider what our ancestors went through—whether they came from Africa or not, and, if they did, that means somebody survived the Middle Passage. It changes what your narrative is for your life today. It changes how you feel about yourself and about your children if you think your great-grandfather was a drunk troublemaker who caused the family’s exile.

One person asked me at work, “It’s over. Why do you care?” And the person who asks me this loves me like I’m a big sister. The answer is because you can’t act like it didn’t happen. You have to act like it happened and try to address it and not be afraid of it.

I think I probably scared a few people when I first went to the Island and just started asking questions. I know the librarian, when I showed her the article, she just skittered away. I didn’t consider that her family might have some skin in this game.

We [African Americans] aren’t all going to be angry. I hate the fact that slavery happened. I understand what it was. But I don’t let that cloud my relationships now.

But I don’t want people to be afraid to share the truth. I want the truth to be told. I want the truth of who my great grandfather was to be different. He was not a ne’er-do-well drunken fighter who just decided to do what he wanted. This was a man who cared about his family, his wife, his children. He went back to work. He continued to help his children. My grandfather Walter went from working as a machinist to owning his own garage. The family kept pressing to have a good life. We all keep pressing to have a good life.

Maria Sharp Montgomery: My name is Maria Suzann Montgomery; my maiden name was Sharp. I came to genealogy in my early teens when I found the family plates in my maternal grandmother’s bible. Unfortunately, I did not take advantage of my opportunity to begin collect oral histories. I actually have only a few memories of my maternal grandfather. He died when I was three. It would be years before I began my search for his family. I had been told there was something that drove them from their home on Gwynn’s Island. After I had chased as many paper ghosts as I could I decided on a whim to visit the island one day. It was beautiful and all I could think of was, “This was the view my grandparents had.” That was it for me. In one day, I found the news articles, grand jury transcript, and original marriage bond. That was one of the best days of my life.

Allison Thomas: E. Allison Thomas is a film and theater producer with a deep love of history and genealogy. She descends from enslavers back to colonial Virginia. She manages the Gwynn’s Island Project website, is co-chair of Coming to the Table’s Pasadena, California chapter, and a co-manager of CTTT’s BitterSweet blog for Linked Descendants.