In Chicago, in 2023, there were 124 active tax increment financing (TIF) districts, which removed over $1.2 billion from the public till, funding otherwise destined for public schools, parks, and libraries. This money is effectively sequestered until the government deems a project worth investing in, which often means the money goes to wealthly, mostly White developers for megaprojects that do more harm than good to the surrounding communities. By the end of the year, Chicago’s TIF accounts contained a fund balance in excess of $3 billion, more than $1,000 per resident in the city of 2.66 million people.

It’s not just Chicago. In fact, tax increment financing is one of the most common local economic development financing tools around. Nationally, I estimate that thousands of municipalities across 49 states operate over 40,000 TIF districts, which collectively remove $40 billion in property taxes from the tax rolls every year.

Organizing Against TIFs

The costs in racial and economic justice from TIF deals are not trivial, and residents and organizations have stepped up to protest the shift of revenues from local schools and services to developers.

When it comes to racial and economic justice and government taxation, federal policy tends to get the most attention. However, state and local taxation are far more damaging.

For example, in February 2025, the Kaneland School District in Kane County, west of Chicago, drafted a complaint as a prelude to suing the City of Sugar Grove over the tax increment financing for a massive development involving housing, business, and warehouse construction known as The Grove. The cost to schools in the district is the loss of an estimated $95 million over a 23-year period.

The school board voted unanimously in favor of filing the complaint. Board member Bob Mankovsky, in justifying his vote, declared that the TIF “purely puts on us the burden of giving millions of taxpayer money that should be educating our students and giving it to billionaires. Let’s just call it what it is.”

Meanwhile, within the city limits of Chicago in the Latinx neighborhood of Pilsen, residents have seen a 40–60 percent increase in their property taxes at the same time the city moved to double the size of the Pilsen TIF. And since 1998, the current Pilsen TIF, which covers the industrial area mostly along the river, has collected over $350 million in revenue. Originally set to expire in 2022, the Pilsen TIF was extended until 2034 by Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez and former Mayor Lori Lightfooot.

Grassroots organization Pilsen Alliance has been at the forefront of protesting against TIFs in the neighborhood since its founding in 1998.

“[Pilsen residents] basically feel like Pilsen is 90 percent gentrified right now. If the TIF expansion happens, it’s basically the nail in the coffin to Pilsen,” Andres Guzmán, a Mexican American activist and member of Pilsen Alliance told Chicago’s Channel 5 News.

More broadly, the Chicago Teachers Union has come out against all TIFs, arguing that eliminating TIFs would free $1 billion for public eduation in the city—an amount that works out to more than $3,000 per pupil in a school distrct that educates an estimated 325,000 students in 634 schools.

Six Reasons Why TIFs Harm Economic and Racial Justice

When it comes to racial and economic justice and government taxation, federal policy tends to get the most attention. However, state and local taxation are far more damaging—shifting the tax burden from the well-to-do to the least well off. And at the local level, TIFs—technical though they may be—are among the leading culprits.

[Chicago’s mayor] has proposed to wind down TIF financing…and create a more equitable common fund for community economic development.

Drawing on data from my hometown of Chicago, here are some of the common issues that make TIFs damaging for racial and economic justice:

- TIFs bleed public money from serving the public. The number one question behind TIFs and other forms of corporate subsidies is a simple one: When is it okay to give public money to a private enterprise for building something not owned by the public? This fundamental question of values and policy is one that’s rarely addressed.

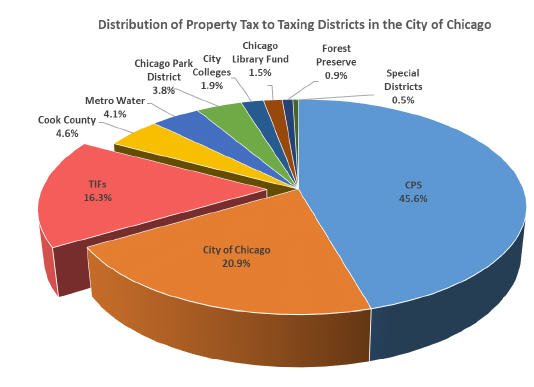

In Chicago, about 56 cents of every dollar collected through property tax is supposed to go the Board of Education to operate our public schools. But, in reality, Chicago’s TIFs take over 16 percent of all proeprty tax dollars collected. This reduces the school share to 45.6 cents on the dollar instead of 56 cents.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- TIFs cause property taxes to rise unnecessarily. One common cause of gentrification are rising property tax rates that disproportionately hit the working poor, people with fixed incomes, undocumented residents, and renters in developer-targeted communities. In Cook County, as of 2023, there are a staggering 433 TIF districts. All the local units of government know the TIF removal process is a reality and when they calculate their annual budgets, they look at the countywide tax base to determine their budgets and how we will be taxed to pay for these public services. The less property there is to assess and tax, the higher the existing properties will be taxed.

- TIFs violate basic principles of equity. One of the fundamentals of a progressive economic policy has to be equity—namely, that the wealthy pay a higher percentage of their income. But TIFs disproportionately benefit the most well off and harm the least off.

So, when a TIF is created in a wealthy area—as is the case all across Chicago—they will accumulate property taxes in an account that can only be used where they are collected. Consider Chicago’s West Loop and South Loop areas: One residential tower built in these places containing, say 100 units, will deliver 100 percent of those new unit’s property taxes to the TIF account. None of those funds will flow to power local government and public services for 23 years (or longer, as Illinois law permits a 12-year extension).

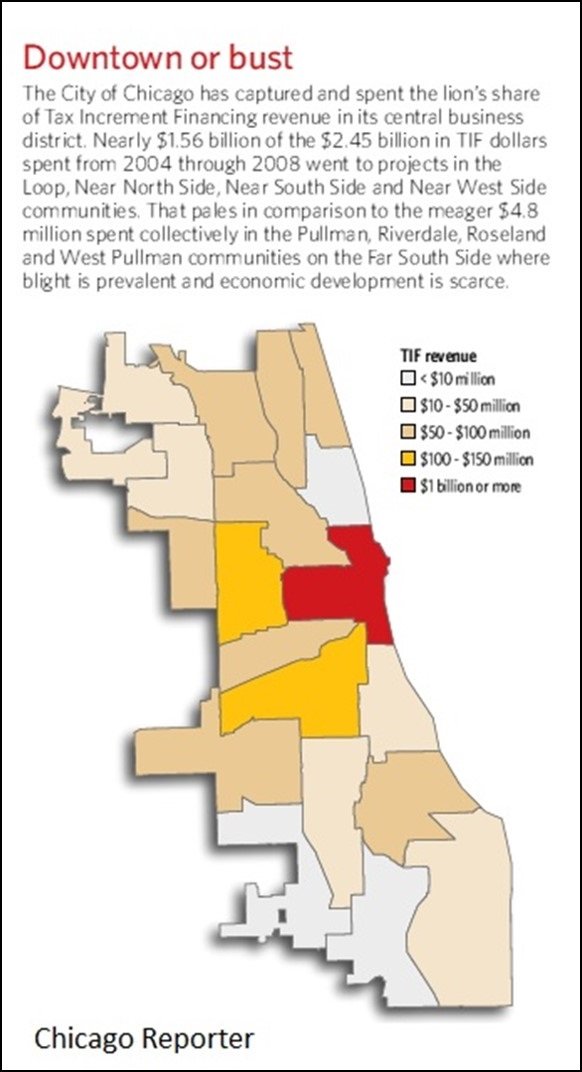

- TIFs divert revenue from where the money is needed to where it is not. Here is a heat map showing Chicago TIF expenditures from 2010, from The Chicago Reporter:

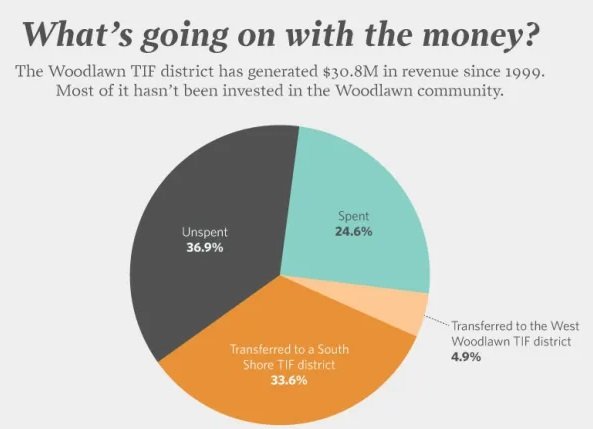

The Chicago Reporter, whose tagline is “Investigating race and poverty since 1972,” has done robust data-driven reporting on TIFs over the years. An article from 2015, “In Woodlawn, questions about the city’s TIF program,” zeroes in on the city of Woodlawn—“a perfect example of a community that could benefit from the City of Chicago’s tax increment financing program, economic development experts say.” Vacant lots, abandoned buildings, and empty storefronts define many parts of the neighborhood. And small-scale entrepreneurs are typically the only people doing business there, along with national chains like Family Dollar that target underserved neighborhoods.

But the paper’s analysis found that most of the money generated in Woodlawn’s oldest TIF district, which includes a swath of 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, has not been invested in the area. According to City data, of the $30.8 million in revenue generated by the district from 1999 to 2014, nearly three-fourths of the money was either unspent or transferred out of the district to repay the city bond debt from the construction of a high school in South Shore, another struggling South Side community.

The Reporter produced this graphic, based on City data from 1999 through 2014:

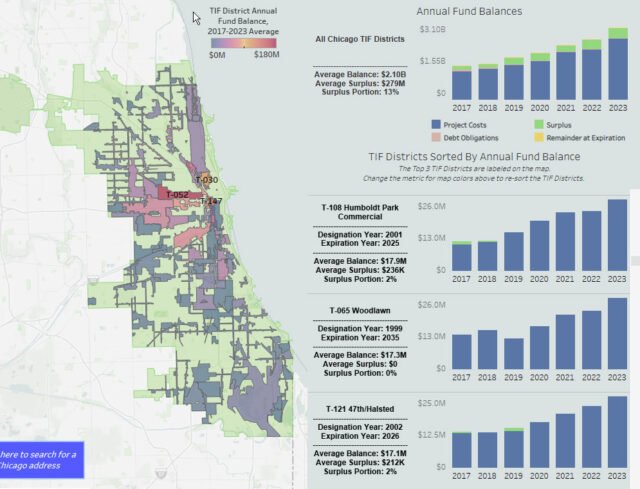

Chicago’s Office of Inspector General has opened a comprehensive TIF data site, showing where the most public dollars are accumulating and have accumulated in the past.

Those familiar with the racial layout of Chicago will notice that neighborhoods with large communitiies of color, such as the Near South and West Sides have extremely low TIF balances, as is to be expected.

TIFs have moved hundreds of millions of dollars out of poor communities while keeping billions in richer, Whiter communities. This is the exact opposite of the rhetoric that is used to promote and defend TIFs.

According to the TIF Illumination Project’s 2021 analysis of all TIF activity in Chicago, majority Black wards contributed more money to the TIF pot and got less back than White wards. It was even worse for Latinx wards. More than that, majority Black wards contributed about 47 percent of the TIF balance in a city that is 28.4 percent Black.

- TIFs pervert the planning procees and promote corruption. Because TIFs can be diverted from public use for long peridods of time, TIF spending is not subject to annual planning, oversight, or evaluation. Most cities’ annual budget processes are hard enough to follow, but at least they are predictable and open to public scrutiny. The TIF planning and award process is the opposite. By the time residents learn of a TIF project, say via a published agenda of a city agency or city council meeting, it is a done deal and they have little chance to stop it.

- TIFs lead to bad-quality development. One more byproduct of the corrupt and opaque TIF process is what I call “TIF bloat.” Since these massive and easily obtained public subsidies reduce the cost of private developments, they also reduce the risk. I believe this process has resulted in the overbuilding of office spaces and retail spaces across the nation.

The Big Picture: When TIF Comes to Your Community, Be Very Cautious

TIFs are not rare. As the nonprofit Good Jobs First reports, TIFs are legal in every state of the country, except Arizona. Additionally, “Six states have more than 1,000 TIF districts each: Iowa (3,340), Minnesota (1,719), Texas (1,378), Ohio (1,278), Wisconsin (1,241), and Illinois (1,238). Another six states have between 450 and 1,000 TIF districts: California, Indiana, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, and Nebraska.”

If you check in your community, you will probably find that some of your property tax revenue—revenue that should be supporting schools and other vital public services—is instead eaten up by TIFs. According to Good Jobs First, “Giving the TIF district first claim on the incremental tax revenue for up to 50 years is to put those corporations ahead of school children, public health, and public safety in the city’s ‘pecking order’ of budget priorities.”

The Chicago Teachers Union has come out against all TIFs, arguing that eliminating TIFs would free $1 billion for public education in the city.In Chicago, current Mayor Brandon Johnson—who as a candidate was strongly supported by the anti-TIF teachers union—has proposed a $1.25 billion bond measure to wind down TIF financing in Chicago and create a more equitable common fund for community economic development.

As Chicago Deputy Mayor of Business and Neighborhood Development Kenya Merritt told the South Side Weekly last summer, “TIF in itself is not predictable nor is it equitable, particularly in areas where you don’t have a strong tax base. What ends up happening is a cycle of disinvestment that perpetuates some of our neighborhoods on the South, Southwest, and West Sides.”

What will happen with Johnson’s proposal remains to be seen. But it does point to the fact that TIFs are not a necessary fact of economic development. And, if we want racial and economic justice to prevail in our communities, TIFs should become an increasingly rare practice.