Throughout the United States and the world, the current economy isn’t working for most of us. Extractive economics harms our environment and our communities—Black, Indigenous, and communities of color most of all. But our economy doesn’t have to work this way. We can create an equitable and democratic economy for all of us.

To transform our economy, we need to network, learn, ideate, iterate, and resource the work together.

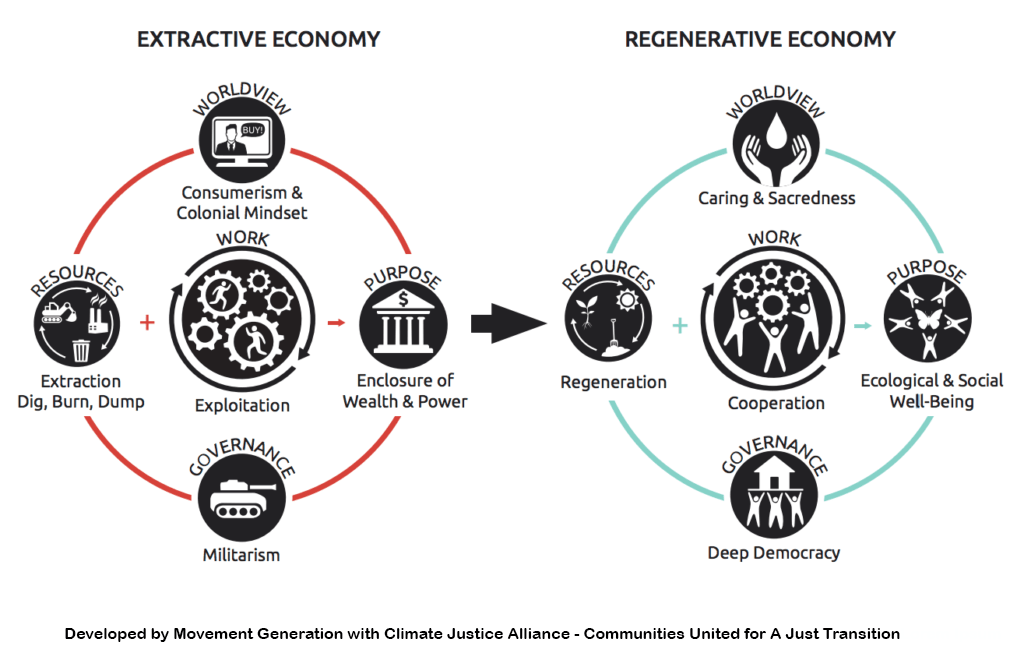

Building a just transition from our present unsustainable, extractive economy to one that is regenerative (and therefore sustainable) is deeply relational and must be anchored in values of solidarity. In the nonprofit sector, it requires transcending the standard hierarchical funder-nonprofit dynamics and replacing them with norms of power sharing and reciprocity.

To transform our economy, we need to network, learn, ideate, iterate, and resource the work together as nonprofits, for-profits, community leaders and members, philanthropic institutions, governments, donors, and investors.

Our organizations have started to map and build these networks in the Seattle area and Washington state. Along with local communal food systems infrastructure, this work includes a range of forms such as cooperative housing, community land trusts, community-controlled real estate and capital, gig worker unions, worker-owned cooperatives, artist collectives, businesses creating products with recycled materials, community gardens, community gathering spaces, and more.

Mapping a Just Transition from an Extractive Economy

At the end of 2020, People’s Economy Lab convened about 20 BIPOC community leaders to create a roadmap for a just transition to a regenerative economy in the Greater Seattle area. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic and a global uprising against police brutality, we were tired of hearing other people talk about us. We wanted to shape our own narrative.

One key barrier that came up again and again was isolation.…We recognized the need to create communities of practice.

We laid out the wicked problem of the extractive economy, mapping it from the perspectives of different participants and communities to get a fuller picture. It was an emotional experience that unearthed considerable trauma. In a room with only members from BIPOC communities present, and after grounding ourselves in somatic practice, we felt safe to share our experiences of living within a system built to extract our labor and resources at the expense of our lives, health, and wellbeing.

While we identified many barriers to our work, one key barrier that came up again and again was isolation. Many of us were already working to disrupt the extractive economy and build a regenerative economy, but we were largely working in silos. We recognized the need to create communities of practice for practitioners and funders to weave our interventions together.

Building Communities of Practice

In Seattle, one tool that is helping build a community of practice among BIPOC regenerative economy practitioners is the New Economy Washington Frontline Community Fellowship (NEW Fellowship) program. This effort is hosted by People’s Economy Lab and Front and Centered.

In its first two years, the NEW Fellowship was funded by Communities of Opportunity (which receives support from King County and the Seattle Foundation) and the New Economy Washington Funders Collaborative. The Seattle Foundation has been a leader in a national movement to build Black funds. This funding, in short, forms part of a broader strategy to transform the economy.

In terms of the fellowship, a community-led selection committee chooses the fellows, who receive financial support, relationship building and peer learning, “just transition” curriculum, customized project support, and the opportunity to showcase work to funders. Unlike many funding opportunities, qualifying projects did not need to have nonprofit tax status or be fiscally sponsored by a nonprofit. To date, fellows have come from nonprofits, fiscally sponsored projects, limited liability corporations, and even a union. The selection committee didn’t care about organizational structure; they only cared about the potential of the community projects to contribute to a just transition to a regenerative economy in King County.

Groups are selected in the fellowship based on their ability to integrate principles of democracy and self-determination, environmental sustainability, equity, and shared economic wellbeing. Fellows include an Indigenous creatives’ collective, food share programs, a systems design consultancy, a driver’s union, and a community-owned real estate developer. Selected teams receive support on how to start their pilot project, coaching on storytelling, and marketing their vision, and, most importantly, access to a network of like-minded social entrepreneurs and potential future funders.

Added value of the fellowship are the relationships developed among participants, community-based organizations, community leaders, emerging businesses, funders, and government agencies. These connections facilitate the flow and collective testing of ideas and mutual support, including and beyond financial resources.

Putting Our Principles into Practice: The Restaurant 2 Garden Case Study

What are the concrete results that are emerging from these fellowships? One example is Restaurant 2 Garden (R2G).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Based in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District, R2G turns restaurant food scraps into compost for the neighborhood’s elder gardeners. In 2020, Joycelyn Chui was working with Chinese-speaking restaurant owners to help them navigate Seattle’s waste management system and found it was adding strain to already struggling businesses. At the same time, one of us, Lizzy Baskerville, managed a community garden for elder Asian neighbors. Chui approached Baskerville to see if she could take food scraps from the restaurants, and the idea for R2G was born.

Though R2G was just an idea in 2020, Baskerville and Chui applied to the first NEW Fellowship cohort. The selection committee chose R2G to join the inaugural cohort because even though R2G hadn’t yet begun operations, its vision of community-controlled composting was very attractive.

Baskerville and Chui officially launched their pilot project in January 2022 after receiving grants from the City of Seattle Department of Neighborhoods and Historic South Downtown. They hired a recent high school graduate Baskerville had known from the local youth empowerment group WILD (Wilderness Inner-City Leadership Development), and they got to work with help from community volunteers. Due to the tight-knit nature of the International District community and the appeal of working outside with others during a waning pandemic, the project attracted a cadre of consistent volunteers, ranging from three to 10 weekly. After a few months, they added regular and dedicated volunteer Jennifer Cheung to the leadership team.

Together, volunteers haul food scraps directly from two Chinatown-International District businesses—Itsumono and Panama Hotel Tea & Coffee House—and turn their food scraps into nutrient-rich compost for the gardeners in the Danny Woo Community Garden one block away. They do everything manually, from hauling buckets of heavy food scraps up steep Seattle hills to chopping the scraps to prepare for precomposting fermentation, to aerating the hot compost, to caring for composting worms, to sifting and distributing the finished product. This process closes the food waste loop, keeping financial and natural resources in the community.

Since the beginning of their compost operations, R2G has donated over 4,000 pounds of compost to more than 50 elder Asian gardeners. Not only is this operation more energy efficient than municipal composting, but it also deepens relationships within the neighborhood. When restaurant staff know where their food scraps are going, it creates a deeper feeling of connectedness: with this model, not only do restaurant staff recognize the farms from which their food is grown, but they directly contribute to the next cycle of food production.

Many people and organizations grapple with this problem. What organizational structure best serves their goals?…It’s a tricky choice.

R2G was, and continues to be, a grassroots organization that doesn’t always fit traditional funding models. Because R2G intends to scale and sell some of the compost it makes—a for-profit model—it’s excluded from some grant funding that prohibits for-profit operations. And because R2G also intends to support the needs of restaurants and gardeners by providing a reduced-price or free service—a nonprofit model—it is difficult to secure private investment and prove profitability. R2G is currently seeking the best structure for its hybrid model to stay financially stable as it transitions out of its pilot project phase.

At its current scale, R2G is funded by the Environmental Justice Fund through the City of Seattle, the King Conservation District, NextCycle Washington, Waste Management Northwest’s Rethink Waste grants program, and individual donations. R2G hopes to secure funding to expand its project to serve upwards of 20 restaurants in the neighborhood, which depends on securing land, purchasing a $200,000 in-vessel composter, purchasing hauling vehicles, and financing site improvements like secure fencing and lighting.

Many people and organizations grapple with this problem. What organizational structure best serves their goals? What organizational structure will give them the best chance of securing financial resources? It’s a tricky choice.

A Second Case Study Project in Development: The Apsara Palace

The Apsara Palace is another Seattle-based project that illustrates these principles.

Dana Wu 吳 淑 如, a 2022 NEW fellow, purchased The Apsara Palace, a Khmer restaurant in the White Center neighborhood of Seattle, in May 2022. They are planning to prepare and sell Khmer cuisine to go, with special dine-in occasions, and intend to eventually develop it into an intergenerational community space in partnership with the Khmer Community of Seattle King County (KCSKC).

Although not open to the public yet, KCSKC has been renting the space that Apsara Palace will use for community programming, like technology workshops for elders and community engagement workshops for the Seattle Department of Transportation and the Office of Planning & Community Development. Soon, KCSKC and The Apsara Palace will launch an intergenerational Khmer culinary arts program to engage elders and youth in continuing and preserving the tradition of Khmer cooking.

Like Restaurant 2 Garden, The Apsara Palace finds a nonprofit structure unsuitable for its goals. Instead, they are pursuing a social enterprise model that permits them to earn profits and invest those profits back into the community and the project, including compensating the Khmer youth and elders involved.

What We Need to Achieve a Just Transition

Both of these projects are just two of many BIPOC-led entrepreneurial endeavors and pilot projects seeding a regenerative economy. They speak to a broader vision—and are incrementally providing building blocks for a solidarity economy in Seattle and beyond.

Fundamentally, this work is grounded in the idea that instead of individuals working in isolation, we need communities and networks of people coming together to dream, share knowledge and infrastructure, learn, and build together. Please join us in networking, learning, ideating, iterating, and resourcing the work! Together, we can—and will—make this vision a reality.