This article comes from the spring 2021 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly.

I have long struggled with calling myself a supervisor. Maybe it activates something in me from my youth—years of hearing my working-class parents complain about their supervisors being micromanagers, always looking over their shoulder, demanding production, scheduling long workdays. My parents would complain about having to put in for vacation and wait for approval from their supervisors, as they struggled to get matching vacation time to spend with us as a family.

As an adult, my discomfort calling myself a supervisor is connected to my experiences holding various leadership positions in nonprofit organizations, including serving as chief human resources officer for a global reproductive healthcare nonprofit. Sure, I participated in management training and learned about different leadership styles. I took solace in identifying my servant leadership style—one that rejects the command and control ways of supervising that date back to production lines in factories. And still, there are organizational structures and so-called human resources best practices that perpetuate a power dynamic—a dynamic that has always felt unsettling for me.

Could it be that the coach in me prefers a more equitable power share when working with junior staff? Or could it be that it is time to retire the term supervisor/manager, especially since our mission-driven work in nonprofits is more knowledge and service than industrial and factory work?1

Indeed, I attributed my distaste for the term supervisor to the history of oppressive management systems dating back to the Industrial Revolution. I was taught that modern management practices began in England with the creation of factories, and in industrialized North America with the cotton gin.

The Brutal Origins of The Supervisor Role

European management thinkers are credited for identifying the function of supervisors into five roles: to plan, organize, coordinate, command, and control. This mechanization of labor and unrelenting drive for production led to long work hours, unsafe working conditions, low wages, and exploitative child labor.

Recently, that narrative has been shattered by documented accounts of violently sophisticated business practices originating on the slave plantations of the Caribbean and in the Southern states of America. In her book Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management, Caitlin Rosenthal, assistant professor of history at UC Berkeley in California, argues that modern management practices—the ways in which supervisors or managers engage with employees to get work done—is rooted in, as Harvard Business Review describes it, “the soil of plantations rather than the dust and debris of the factory floor.”2

In her review of many business records of slave owners, Rosenthal found that modern business management practices employed by corporations and nonprofits—creating middle managers, performance management, productivity analysis, and workforce planning—can all be traced back to the management of plantation slavery.3

I’ve come to appreciate that my visceral reaction to the title supervisor is not related to industrial work. My reaction is ancestral, related to slave work.

At CRE, we define supervision as a process marked by values-based support, feedback, openness, continuous learning, and partnership. It is inclusive and equitable, with dual responsibility for success in which both supervisor and supervisee are equally invested in creating a fulfilling, respectful, and mutually beneficial developmental relationship.

And yet, even with a definition and good intentions to reinvent the supervisor role, these matter less than the inherent racist management system that guides how we interact with our teams. This management system was designed to value white lives and white livelihood over Black lives and Black livelihood. The system was designed to demand productivity and profit for the benefit of the slave owner at the physical, mental, and emotional expense of the enslaved. As Rosenthal documents, we inherited the oppressive system and practices, which includes inheriting the title supervisor. We can rid ourselves of the supervisor title—but to truly rid ourselves of the embedded racism in organizational leadership is to envision a different paradigm.

What would we call ourselves if we were not using terms rooted in oppression? What would we do differently?

Transition from Analysis to Anchoring a New Way Forward

Coronavirus has made the mighty kneel and brought the world to a halt like nothing else could. Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality,” trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality.

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

—Arundhati Roy4

The notion of the pandemic as a portal shifted my perspective from what was to what can be created. My thinking shifted further when I heard Dr. Angel Acosta describe the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with four hundred years of reckoning with racism as COVID-1619.5 As an educator and social justice facilitator, he offers a healing-centered framework for leadership and organizational development.6

I began to question, what would it be like to center health and wellness in our approach to our work with our teams?

Knowing that being a supervisor is tied to the beginnings of a management system that began with the brutality of enslaving Black people, it’s no surprise that, in general, workers report feeling that they are being overworked, are stressed, and that they are experiencing mental health challenges. One in five adults in North America experiences a mental health challenge in a given year, and there is some evidence to suggest this is higher among nonprofit staff.7

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The stress related to being a leader of color8 and for supervisors in POC-led nonprofits on the COVID frontlines9 understandably leads to health problems and burnout.

In Dying for a Paycheck, by Jeffrey Pfeffer, the author notes that in a survey of almost 3,000 people, 61 percent of employees said they had become sick from workplace stress, and 7 percent that they had been hospitalized.10

A 2011 study by Opportunity Knocks highlights factors that cause nonprofit employee burnout.11 Half of the respondents indicated being burned out.12 Much of the burnout was related to workload and expectations to do more with less—as is often the case, especially during staff turnover or when positions are eliminated. Seventy-four percent of nonprofits reported that they distribute responsibilities among their current staff when positions are eliminated.13 Pushing staff to work harder, longer, and with fewer resources is toxic for staff and costly for nonprofit organizations in more ways than one.

In 2019, the World Health Organization listed burnout as an occupational phenomenon, described in the international classification of diseases as:

a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions:

-

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion;

- increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and

- reduced professional efficacy.14

Let’s go back to the origins of modern management rooted in slavery. What if we did the exact opposite of what being a supervisor was created to do? What if we not only abandoned the term altogether but intentionally centered the well-being of our people first? What if being antiracist meant focusing on the health of Black lives and Black livelihood, not as an afterthought or a statement on our website, but as the primary reason we work together, for our collective healing and liberation?

Some may say, “But we can’t create policies for improving the health and livelihood of Black staff. What about other identities?” We have recent history of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 improving the livelihood of Black people by prohibiting “discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.”15 Changes in racist policy to make things better for Black people leads to making things better for all people, including Black people who are also LGBTQ, pregnant, disabled, gender nonbinary, and other protected classes, as is the case in New York City Human Rights Law.

Others may say, “We can’t prioritize employee well-being. We have to focus on our bottom line, our deliverables, and funder demands. Our mission to service our clients is our top priority. Employees have to expect to work hard for the mission. We’re not corporate America, we just don’t have the resources to focus on wellness at work.”

Let’s compare what we used to say we couldn’t do, or could only offer as “perks,” to what we have done during the dual pandemics of COVID-1619.

As supervisors, managers, leaders we have:

- shifted to all staff working remotely, allowing for greater flexibility and trust;

- acknowledged racial trauma and given time off for Black staff traumatized after the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd;

- held conversations in the workplace about racism, antiracism, and specifically anti-Blackness;

- declared that Black lives matter, and made commitments to support that both externally and internally;

- moved beyond the performative calling for intersectionality to holding space for the unique needs of LGBTQ staff of color, especially Black trans women;

- eased work goals and so-called productivity demands during the crisis;

- checked in with staff on their well-being, not just on work-related tasks;

- fostered community care with wellness resources as a team;

- rescinded HR policies that restrict staff from earning an income through self-employment or a “side hustle” if they were furloughed or had work hours reduced during the pandemic;

- supported flexible working hours during the day if a team member needed to assist their children with remote learning;

- encouraged logging off to take a walk, make a meal, or even take a nap to recharge during the day;

- created walk and talk phone meetings to reduce Zoom fatigue and encourage movement and getting fresh air as a healthy alternative to sitting in front of the computer for long hours;

- provided standing desks and other ergonomic equipment needed for work-at-home setups.

We will not go back to normal. Normal never was. Our pre-corona existence was never normal other than we normalized greed, inequity, exhaustion, depletion, extraction, disconnection, confusion, rage, hoarding, hate and lack. We should not long to return, my friends. We are being given the opportunity to stitch a new garment. One that fits all of humanity and nature.

—Sonya Renee Taylor

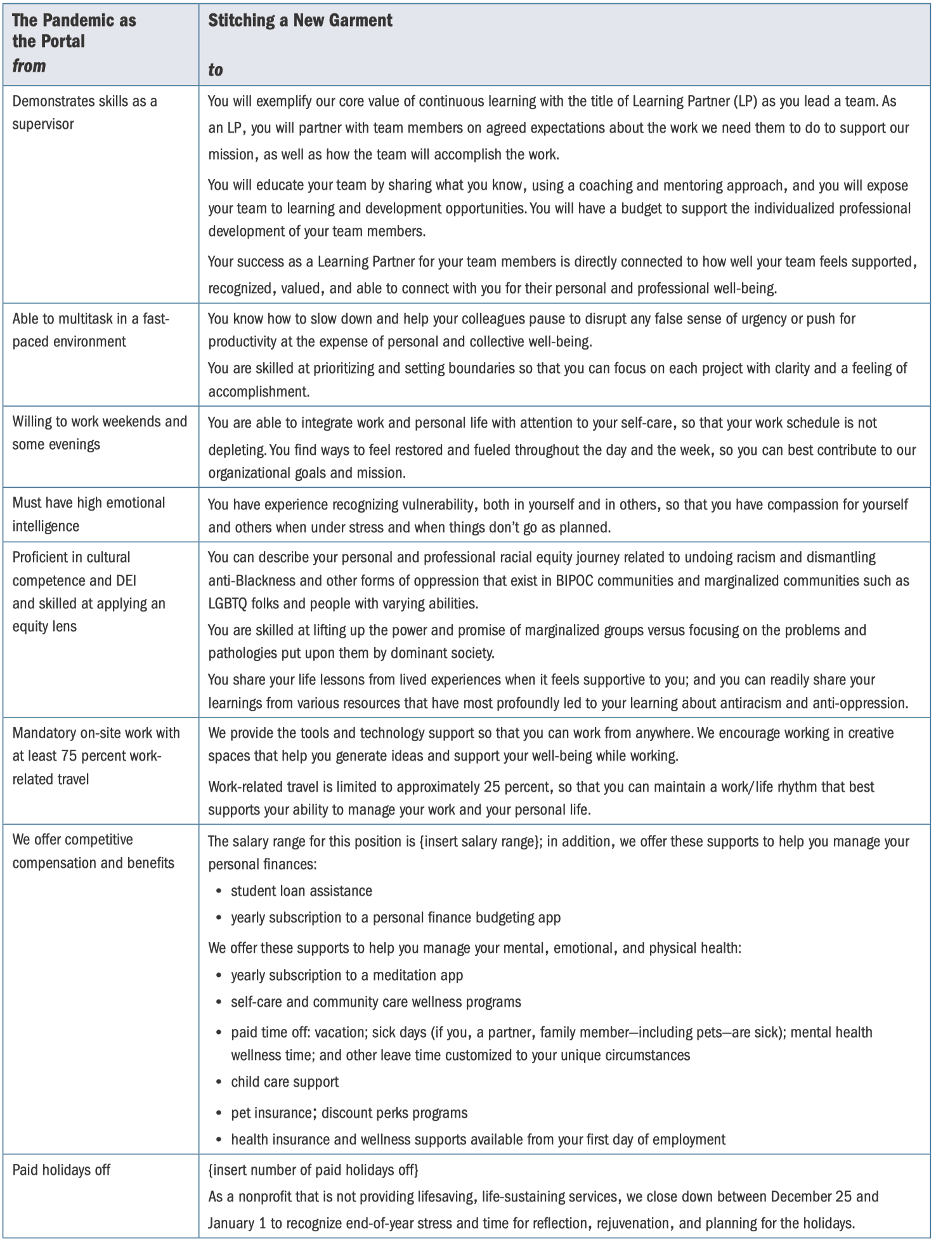

Indeed, we have an opportunity to reflect on this past year and create something new. What would that new garment look like? For example, what if we described our open positions using the following paradigm shift?

So, yes—in building antiracist organizations, we can start by changing our name. We can stop calling ourselves supervisors, managers, chiefs, or any other label that’s rooted in racism and the replication of harmful work norms. More important, we can view this pandemic as a portal, rip away the harms of the past, and stitch a new garment by changing what we do and how we do it.

The thoughts and opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of CRE.

Notes

- Adam Bryant, “Is it time to retire the title of manager?,” Strategy+Business, January 30, 2020.

- Harvard University Press catalog page, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management by Caitlin Rosenthal; and see Caitlin Rosenthal, “Plantations Practiced Modern Management,” Harvard Business Review, September 2013.

- Kimberly Adams, “The disturbing parallels between modern accounting and the business of slavery,” Marketplace, August 14, 2018.

- Arundhati Roy, “The pandemic is a portal,” Financial Times, April 3, 2020.

- Angel Acosta, “The 400 years of Inequality timeline,” August 6, 2020, YouTube video, 2:44.

- See “Expertise,” Dr. Angel Acosta, accessed March 22, 2021.

- Center for Nonprofit Excellence, “Mental Health Issues among Nonprofit Staff: Addressing the Elephant in the Room,” online learning forum, March 28, 2018.

- Jim Rendon, “New Report Details the Barriers That Leaders of Color Face at Nonprofits,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, June 4, 2019.

- Jen Douglas and Deepa Iyer, On the Frontlines: Nonprofits Led by People of Color Confront COVID-19 and Structural Racism, Building Movement Project, October 2020.

- Jeffrey Pfeffer, Dying for a Paycheck: How Modern Management Harms Employee Health and Company Performance—and What We Can Do About It (New York: HarperCollins, 2018).

- Engaging the Nonprofit Workforce: Mission, Management and Emotion (River Forest, IL: Opportunity Knocks, January 2012).

- Ibid., 8.

- As parsed out in “Nonprofits Making Moves to Avoid Employee Burnout,” NonprofitHR, March 1, 2013.

- World Health Organization, “Burn-out an ‘occupational phenomenon’: International Classification of Diseases,” May 29, 2019.

- “Legal Highlight: The Civil Rights Act of 1964,” U.S. Department of Labor, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Administration and Management, accessed March 20, 2021.

Bringing over twenty-five years’ nonprofit experience, Kim-Monique Johnson, a senior consultant at CRE, provides support to organizations through organizational development, curriculum development, group facilitation, and diversity, equity, and inclusion strategies. She identifies as a Black, cisgender lesbian, who recognizes the importance of creating space for naming identities and lived experiences. Johnson has experience in healthcare, human resources, and leadership coaching. She is passionate about helping new managers as well as seasoned executives who face new challenges related to organizational management, diversity, racial equity, and inclusion. For leaders who wonder how to show up as their authentic selves, for people of color who may also be part of LGBTQ communities, she offers coaching to support their well-being and success. Before joining CRE, Johnson served as the chief human resources officer at the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the VP of talent at the Food Bank for New York City. Her global experience includes a year as a volunteer sexuality education teacher in Gabon, Central Africa, and co-leading the first LGBTQ multiyear training for healthcare providers in Lima, Perú. Johnson is a certified Wiley Everything DiSC® workplace facilitator, a senior certified professional with the Society for Human Resource Management, and certified in the Clark Wilson 360 Feedback Survey. She is also certified in Energy Leadership Coaching with the Institute for Professional Excellence in Coaching (iPEC). She obtained a BA in psychology from Johns Hopkins University, and an MSW from the State University of New York at Stony Brook.