Review of The Five Demands. Directed by Andrea Weiss and Greta Schiller. Icarus Films, 2023.

Greta Weiss and Andrea Schiller’s newly released documentary The Five Demands tells the story of how the first state-mandated, state-funded educational opportunity program in the United States gave rise to a student movement for multiracial solidarity. It features present-day interviews of students from the classes of the early 1970s who were some of the only students of color at CCNY. The film also features the program founders, counselors, and faculty that helped champion the vision of the “Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge” (SEEK) program.

Student activists today are still organizing for justice at their universities, from equitable pay for campus jobs to better housing conditions. Even before the Supreme Court’s June 2023 decision invalidating affirmative action in higher education, Black and Latinx students faced stark underrepresentation. At the same time, this era has also seen new forms of student activism (such as rising graduate student unionization). Looking at the history of the students at CUNY offers a valuable window into struggles today.

How SEEK Came to Be

The term “affirmative action” first appeared in a 1961 executive order signed by President John F. Kennedy, which actively prohibited discrimination in the hiring process. Two years later, Kennedy urged college presidents and trustee boards across the country to advance civil rights by extending equal educational opportunity to all.

In the 1960s, colleges and universities created several programs to address problems resulting from racial segregation in America. The original goal, according to the federal mandate, was not to admit a select few to the nation’s elite institutions but to create a truly equitable education system. However, the action did not match the rhetoric: lacking adequate support, colleges hosting these initiatives faced widespread budgetary issues. Declining state investments beginning in the 1970s made these efforts yet weaker.

But not everywhere. The 1960s were an era of educational experimentation. At this time, the City College of New York (CCNY)—the founding institution of the City University of New York system and the first free public university in the United States—piloted a program designed to desegregate the student population, then 97 percent White. Established by the New York State legislature in 1965, the SEEK program touted an official commitment to recruit “economically and educationally disadvantaged” students to bring in Black and Puerto Rican students from Harlem.

Amidst The Five Demands’ panoramic shots of beautiful campus buildings, SEEK students tell the story of what the program represented, not only for them but for the city at large. “SEEK was the way in which the city of New York attempted to make up for its racist doctrines prior to [its] arrival,” states poet Louis Reyes Rivera (class of 1974). The school had been mostly hospitable to Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants. But the Black and Puerto Rican students who lived around the school were not likely to walk the campus until SEEK began.

“The learning process is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot.”

Artist and educator Esperanza Martell (class of 1978) explains how in her experience growing up as a poor and working-class Puerto Rican child in the city, college education was never even on the table due to substandard education and racist treatment: “I wasn’t really taught how to read, how to write. And they had specific programs [that] they tracked us into. So, the program I was [put] into was to be a nurse’s aide…learn how to take care of people. So, I didn’t even think about going to college.” Black Studies professor James Small (class of 1975) puts it plainly: “You weren’t left out of college because you were dumb or because you couldn’t learn, you were left out because of the way society’s structured…and you weren’t structured into that.”

The campus climate was generally hostile to the newcomers. “People were not pleased with this influx of Brown and Black people to their hallowed halls,” says Covington. Counselors reminisce how resistant many faculty were to SEEK students: questioning their intelligence, singling them out in classes, and making sure that White students were aware that they had entered the college with lower test scores and through a special program. It became clear that a radical program needed a radical faculty.

As SEEK founder Allen Ballard puts it in the film, CCNY President Buell Gallagher “put the weight of the presidency behind the SEEK program” to recruit academics that were better suited to SEEK’s high aspirations. “And who did he get?” June Jordan, Toni Cade Bambara, Adrienne Rich, and Audre Lorde, who noted the following about teaching at SEEK: “The learning process is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot.”

These figures brought powerful antiracist, feminist views to the Black and Puerto Rican student body, offering the students the space to recognize the intellectual rigor of their own experiences. The film weaves in illuminating moments from seminars, where SEEK students reflect on their places as second-class citizens in a country that their ancestors built.

Staffing SEEK with radical faculty gave the students a sense that Black and Latinx culture was a political strength. While most of the CCNY student body was not politicized, a sharpened sense of revolutionary consciousness grew on campus, fed by a canon of political texts from Du Bois to Fanon that paired well with the growing sense of opposition to the Vietnam War and movements for political independence from Africa to Latin America.

The leadership from the Black and Puerto Rican student community came from newly formed organizations in the community—the Young Lords, Black Panthers, and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—and many helped form new groups, such as the Onyx Society and Puerto Rican Students Involved in Student Action (PRISA). “We came together because we were being educated together,” says Felipe Luciano, cofounder of the New York chapter of the Young Lords. Freedom was a worldwide demand—and the students were beginning to understand that civil disobedience was the only way to realize the liberation of people of color.

The Five Demands

It is a well-known fact that in 1968, student protests erupted at universities across the world in concert with larger rebellions for labor and civil rights. In the United States, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. was a catalytic event. Many moved from an attitude of nonviolent resistance to a much more radical position. Videos from NBC News and other mainstream media at the time show reports of students nationwide demanding the removal of military programs and the appointment of Black administrators.

In this historic moment of racialized struggle within and beyond the university, a negotiating body of Black and Puerto Rican students at CCNY put forward five demands to transform their school. They were:

- A separate school of Black and Puerto Rican Studies

- A separate orientation program for Black and Puerto Rican students

- A voice for SEEK students in the setting of all guidelines for the SEEK program, including the hiring and firing of all personnel

- That the racial composition of all entering classes reflect the Black and Puerto Rican population of New York City’s high schools

- That Black and Puerto Rican history and Spanish language be a requirement for all Education majors

The demands were submitted in October 1968 to President Gallagher, who did not respond.

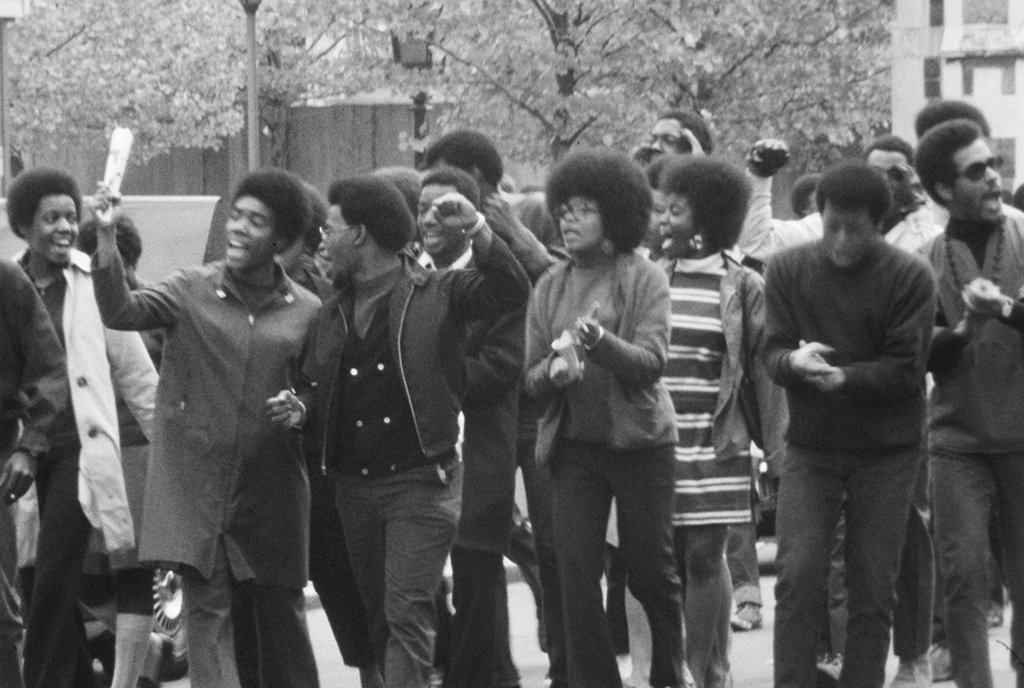

“You take action if your words are falling on deaf ears, if nothing is happening, if you see no movement,” says Rosalind Kilkenny McLymont (class of 1971). At 6 am on April 22, 1969, students chained the gates of CCNY shut. The student takeover began; the campus was under their control. At a campus town hall, Black and Puerto Rican students presented their demands with reasoned arguments. Many faculty dismissed them as uncivilized and unserious, while others stood in support of the SEEK students.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

While the student takeover started as a symbolic line in the sand, it sparked real upheaval when campus security guards—who were mostly Black—refused the administration’s order to remove the protestors from the grounds. They were all fired, and the students responded with a sixth demand that no discussion would occur until they were all reinstated—which President Gallagher assented to immediately. Labor solidarity between the Black campus workers and students of color proved to be an effective tactic to take the strike to the next level.

Movements often call up difficult questions and force people to take a side. White students were not admitted through the gates and were forced to consider for the first time what it felt like to be locked out of an institution of higher education. For some of the Jewish students on campus who were aware of the nation’s history of antisemitism, says Jeffrey Gurock (class of 1971), the shutdown forced them to ask: “Where do we fit in to this moment in time?”

Footage from the gates shows White students rallying in support outside the gates holding signs in support of the five demands, while others claimed that the White majority was being unfairly excluded from their education. “They were not the majority, even though they said they were,” explains Naomi Chesman Smith (class of 1970) after seeing a recording of herself supporting the strike to a group of angry objectors. “It’s part of history that White men often feel like they are the majority, like what they say is truth. They try to erase everything else.”

History was being made whether White men liked it or not. The students declared the campus “Harlem University,” renaming buildings after revolutionaries, holding political education classes, offering childcare, and inviting local and national leaders to speak in support.

“We came to inherit this; we didn’t come to destroy it”

Strikes Seek Change

Strikes create change when they disrupt the status quo. And while the administration dug its heels in and blamed a lack of progress on the students, President Gallagher also refrained from using city police to break the strike. Twelve days after the takeover, local media reported that President Gallagher was ready to agree to some of the student demands—but the local government stepped in just as this partial settlement was in sight. The Board of Education, acting on Mayor Nelson Rockefeller’s order, pressured Gallagher to resign and appointed Joseph L. Copeland, who immediately went through academic records to expel students and threatened to remove students with police force. The takeover ended two weeks and three days in, on May 6, 1969.

When the campus reopened, violence broke out. Police surveillance footage and interviewees show Black women being assaulted at the gates by a group of hundreds of White men, but the press reported that Black and Puerto Rican students had incited riots and provoked a police crackdown. Organizers were beaten, arrested, and interrogated. When the student chapel was burned down, the mainstream media blamed it on the student protestors. But the organizers of the student occupation refuted blame: “Our position was, you don’t burn down what you have come to use. We came to inherit this; we didn’t come to destroy it,” Small says.

At CCNY and beyond, the national story of higher education and who deserves it had been rewritten.

As other campuses began to protest in solidarity, university administrators finally agreed to consider the main demand: that every CCNY freshman class be made up of 50 percent Black and Puerto Rican students to better reflect the population of Harlem. Politicians called this an unacceptable quota system, and the media reported that CCNY’s scholastic excellence was in jeopardy. But faculty supporters argued that the school had a responsibility to open educational access to the community.

While SEEK program directors and student organizers wanted to expand the SEEK program and target Black and Puerto Rican student admissions, CCNY administrators decided on an “open admissions” policy, which prescribed that the only requirement to enroll at CCNY was a New York City high school diploma. Allen Ballard said that even then, he warned that this was a bad idea: “The university…took on a situation it was not financially able to handle.” While equality was being negotiated at the table and in the press, it was being undermined in the balance sheets. Mayor Rockefeller proposed budget cuts to the college, including ending the SEEK program, “destroying the university by defunding it,” Chesman Smith explains.

But an important battle had been won. During the 25 years of open admissions, hundreds of thousands of Black and Latinx students entered the CUNY system. At CCNY and beyond, the national story of higher education and who deserves it had been rewritten. In footage from the 2016 commencement ceremony almost 50 years after the student takeover, salutatorian Orruba Alamansouri credits CCNY for making her the first in her Yemeni family to attend college: “I fought to be allowed to pursue an education, for the right to be here.”

The Work to Come

The documentary ends with a scene from a 2019 celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the student takeover. Organizers from the old days congregated to celebrate their historic achievement, and Francee Covington addressed the now middle-aged crowd: “I’m sure you’ve all heard that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice. The arc does not bend itself; we do that. People of conscience do that.”

Even more austerity has been imposed on higher education since this scene was filmed. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hundreds of universities imposed budget cuts, exacerbating longstanding inequities by reducing programs and closing campuses. Some 48,000 academic workers went on strike for living wages at the University of California. The student loan crisis looms large, as the same Supreme Court that repealed affirmative action also struck down President Biden’s debt relief plans. All these issues are undergirded by the fact that universities became less funded and more expensive at a time when more students of color were seeking to attend them.

Too often, piecemeal approaches (such as measures implemented by the Biden administration in the wake of its Supreme Court defeat), while helpful in making college a little bit cheaper for some, fall far short of the dream of open access that the CCNY activists believed in.

The strikers at CCNY in 1969 insisted that higher education must not exclude those who have been forced into poverty and failed by education all their lives. They had a more radical understanding of why institutions for the public were not in fact open to everyone—and how to change them for the future.

The CCNY student takeover steered the university toward this alternative future for higher education. By starting from the fact that racism and poverty were the reasons that CCNY was not truly open to the Black and Puerto Rican students who made up the New York public school system, the movement made merit-based admission a moot point.

The Five Demands shows not only how hard those students worked to change their institution to create a more equal world but also how far we are from realizing their vision of radical inclusion. It is a reminder that a vision of education for all is not a pipe dream. Despite the many obstacles, it is our responsibility today to fight for the higher education system that we deserve.